Football History As Told By Sporting Goods Catalogs: Nose Guards and Face Masks

The equipment used by football players at different points in the game's history tells us much about the game during each period, making period sporting goods catalogs an interesting archival source of football history. My first post examining catalog items covered the history of footballs and the equipment needed to maintain them, while the second post dealt with football shoes and cleats. The series now turns to facial protection. That is, the methods of protecting players' faces before helmets, during the leather helmet days, and in the first twenty years of plastic helmets.

Early football players did not wear equipment to protect their heads or faces, but particular rules changes led football away from the open rugby-style game of the 1870s and 1880s to the slug-it-out, mass game of the 1890s. The increased number of collisions and piles brought more broken noses, black eyes, and similar injuries, leading Harvard's captain, Arthur Cumnock, to devise the nose guard in 1892. Cumnock sold his rights to the device to John Morrill, who modified and commercialized the nose guard.

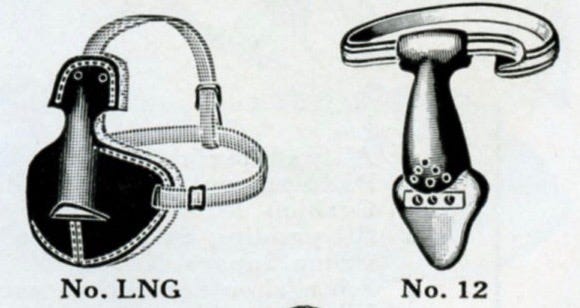

In an age when the amount of protective equipment worn by a player was considered inversely related to one's manhood, most who wore a nose guard had existing facial injuries or strong-willed mothers. Even then, the nose guard was less than ideal since players with broken noses had difficulty breathing through the nose. At the same time, clenching the device between the teeth made it difficult to breathe through the mouth.

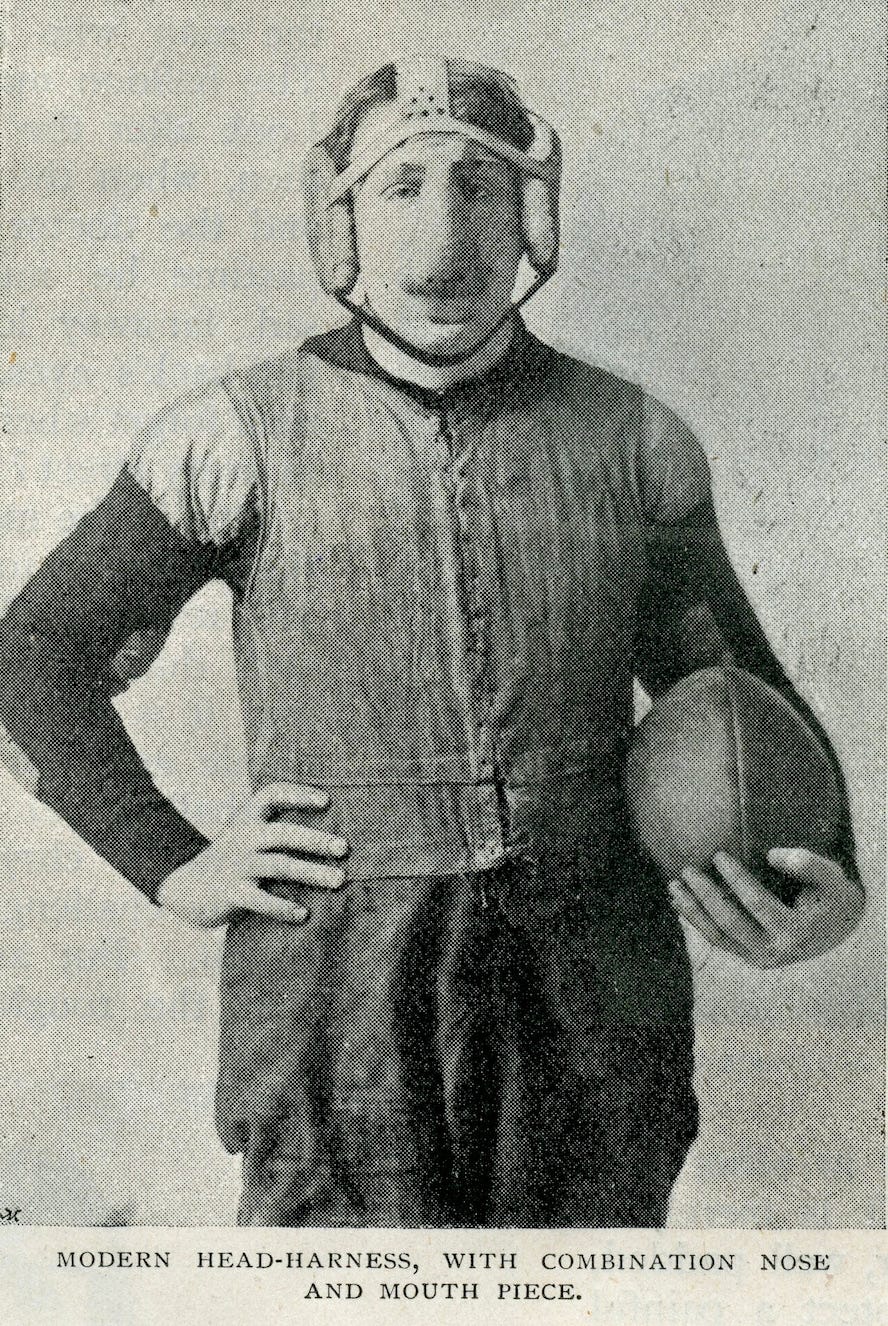

The use of nose guards peaked by 1910 but remained in use and available in sporting goods catalogs until the 1940s. Notably, during much of the nose guard's reign, players did not wear helmets per se; as seen in the image above, they wore head harnesses that more closely resembled today's wrestling headgear than modern football helmets.

The 1920s and 1930s saw football's flimsy headgear shift toward rigid helmets with hard protective shells encased in softer leather. The nose guards of the 1890s, which rested on the face, evolved into partial and full-face masks. Fiber- and steel-reinforced, some strapped around the head while others attached to the helmet, covering the face.

Another form was the executioner's mask, which is the likely reason we call today's devices face masks.) These limited peripheral vision and were exceedingly hot, but they were effective in protecting previously broken noses. It is fair to assume that no one wore these devices without a pre-existing condition.

The increasing rigidness of helmets led to the next great leap in facial protection with the birdcage's arrival. Unlike devices that rested on the face, birdcages protected the nose and eyes by attaching to and extending from the rigid helmet. Besides protecting facial injuries, they also allowed players to wear eyeglasses while playing football. Again, these were worn exclusively by players with injuries or eyeglasses, but they were sufficiently common that the NCAA debuted the face masking penalty in 1937.

Birdcages protected the top half of the face, not the jaw. Some period players with broken jaws, such as 1942 Heisman Trophy winner, Frank Sinkwich, wore separate, custom-made devices covering the bottom half of the face.

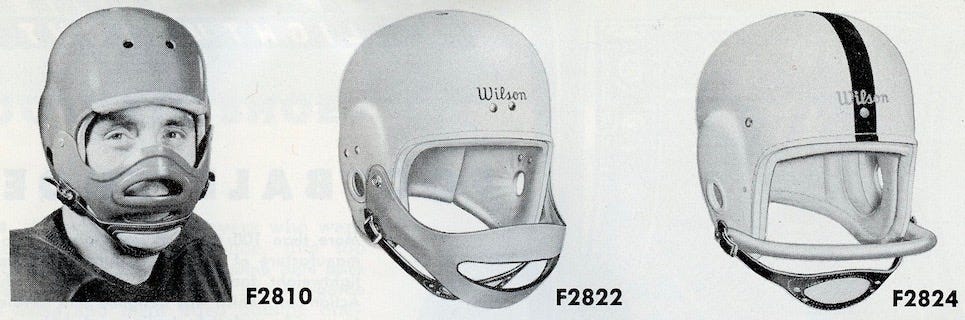

Riddell introduced plastic helmets in 1940. Those plastics were unavailable for civilian purposes during WWII, so plastic helmets did not gain popularity until the late 1940s when they ignited one of football's great equipment debates. The debate boiled down to whether rigid helmets, birdcages, and face masks of various designs caused more injuries than they prevented. The concern about birdcages injuring others led to further development of devices that rested against the face, harkening back to the nose guards of the 1890s and executioners' masks of the 1920s and 1930s. These masks did not protrude from the helmet or injure other players, but they offered less protection for the wearer, ultimately leading to their demise.

Football headed in the direction of the modern face mask, but there were many interpretation of that form in the 1950s. One version, popularized by Otto Graham, was a transparent plastic bar that extended from the helmet. Its shortcoming was the tendency to shatter, particularly in cold weather, so teams in the North could not rely on it.

Another version with a short shelf life had wide gray plastic "lips" that were unsightly and limited visibility. (One or two of these still circulated among my early 1970s grade school team. Thankfully, they were never attached to my helmet.) Shatterproof clear plastic soon replaced the gray plastic among teams that cared about their appearance and performance.

Plastic and rubber-covered metal bars were the most popular devices by the early 1960s, with the plastic-only versions soon fading away. The rubber-cover metal bars combined protection and versatility. The single-bar face masks initially used by many positions were supplemented with horizontal and vertical bars, hooks, and other forms for increased protection for interior linemen. These morphed into full cages. Backs stayed with single bar masks for a while but eventually opted for the full cage's protection, though with limited or no bars at eye level.

There have been stylistic changes to face masks since then and some functional changes as the science and engineering of facial protection evolved with that of helmets, but today's face mask appears quite similar to those of the 1970s.

The various forms of facial protection and the mandated use of mouthguards (high schools in 1962 and the NCAA in 1973) dramatically reduced facial and dental injuries. Broken noses, lost teeth, and other acute facial injuries common in the 1940s largely faded away. Unfortunately, the head and face's enhanced protection resulted in changes to blocking and tackling techniques that brought their own set of problems; many of those techniques have since been banned or otherwise removed from the game through improved coaching.

Football Archaeology is reader-supported. Click here to buy one of my books or otherwise support the site.