The Origins of Checkerboard Fields and Seven Men on the LOS

The greatest challenge facing football today is concern about its link to brain injury and CTE. Safety-related concerns are not new to football as the game's leaders have enacted a variety of rules over the years to reduce the number of deaths and injuries. Football aficionados know the most important set of safety-related rules gained approval in 1906, but significant rule changes also occurred in 1903. Unfortunately, these had limited impact on player safety and helped set the stage for more radical reforms three years later.

Football's rule makers of 1903 made three key rule changes to enhance player safety. The first instituted the roughing the punter penalty, which gained approval for reasons that are not obvious and will be discussed in a subsequent post. The second rule change required offenses to have seven men on the line of scrimmage at the snap and the third brought the checkerboard pattern that marked football fields from 1903 to 1909. This post will cover the second and third rules changes, but to understand the need for these rules, we need to step back further in football history.

American football's direct ancestors were centuries-old games played in England in which the population of men from one town attempted to kick an inflated pig's bladder into a neighboring town. The neighboring town's men objected and fought to kick the bladder in the other direction. Those games evolved into a loose confederation of games that split into the Association game (soccer) and rugby in the mid-1800s.

The 1869 Rutgers-Princeton game, considered to be the first American college football game, used rules resembling soccer, but the colleges settled on playing a slightly modified form of rugby in 1876. Those teams had fifteen players per side until Walter Camp and his Yale buddies convinced everyone in 1880 that playing eleven players per side would make the game more open and entertaining.

As the game developed over the next two decades, it became common practice for the eleven offensive players to align in the traditional T formation, which had seven men on the line of scrimmage with little or no spacing between them. The quarterback aligned a step or two behind the center with the other three backs in a straight line four to five yards behind the line. (In an earlier version of the alignment, the backs formed a diamond so the deepest man was the "fullback," the middle backs on either side were the "halfbacks," and the man closest to the line was the "quarterback.")

Tackling below the waist, but above the knee, became legal in the late 1880s and this made open field running less effective. As a result, football evolved into a smashmouth, "momentum and mass" game. The football rules of the early 1890s did not limit the number of players in motion at the snap or require a specific number of players to be on the line of scrimmage at the snap. Since multiple players could be in motion, teams used "momentum" plays in which several players took running starts, hitting the hole as lead blockers shortly after the snap. An 1895 rule limited teams to one man in motion at the snap, effectively eliminating the momentum play, so offenses focused on "mass" plays which had multiple blockers lead the runner through the hole. Since only one man could now be in motion at the snap, teams moved their lead blockers into better position by aligning in the "guards back" and "tackles back" formations. These formations had the guards or tackles aligned behind the line of scrimmage -like the backs- with the guards or tackles preceding the runner into the hole. Such plays resulted in occasional breakaway runs and many boring, but dangerous, piles of players.

As pressure mounted for football to cure its ills, an area of focus for the rule makers of 1903 was to eliminate mass plays and they did so by implementing a rule requiring teams to have seven players on the line of scrimmage at the snap. This rule put an end to the "guards back" and "tackles back" formations, and mass plays as a result. Not everyone supported the new rule, and its opponents succeeded in revising it in 1904 so only six men had to be on the line of scrimmage. Still, the seven-man rule returned for good in 1910, so teams wanting to send multiple blockers through the hole generally needed to pull linemen to do so.

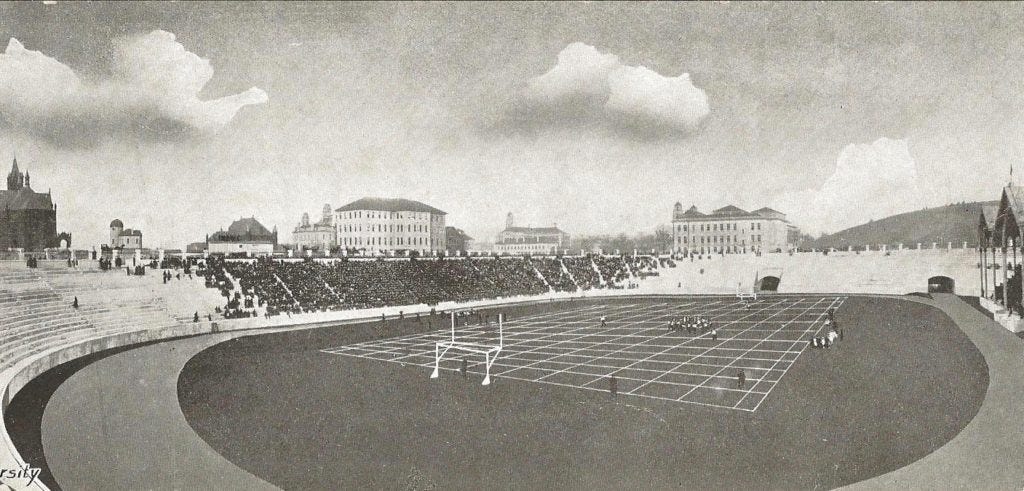

A second rule enacted in 1903 reversed the longstanding rugby rule requiring the player who received the snap to lateral the ball to a second player, who could then run with it. Intended to open up play, the player receiving the ball from center (e.g., the quarterback) could now run with it provided they crossed the line of scrimmage five yards left or right of the center. To help the officials assess compliance with the rule, the field was marked with lines five yards apart running perpendicular to the yard lines, creating a checkerboard on the field. Facing opposition to this rule as well, the rules committee compromised by allowing the quarterback to run with the ball only between the 25-yard lines. Likewise, the checkerboard field markings applied only between the 25-yard lines.

The following year, the rules changes to allow the quarterback to run with that ball everywhere on the field (provided he was five yards right or left of center), so the checkerboard ran goal line to goal line. The checkerboard gained a second purpose in 1906 when the forward pass became legal since the rules required the passer to be at least five yards right or left of the center at the time he threw a pass.

Still looking for ways to open up the game, the 1910 rule committee allowed the player receiving the snap to run with the ball anywhere along the line of scrimmage. (Every quarterback sneak since then says, "Thank you.") In the passing game, they removed the five-yard horizontal restriction as well, but replaced it with a vertical restriction: passes could be thrown anywhere along the line of scrimmage as long as the passer was at least five yards behind the line. The rule requiring the passer to be at least five yards behind the line of scrimmage remained a part of the college game until 1945. (Every quick slant and bubble screen since then says, "Thank you.")

The rule changes of 1903 were the most significant attempt to reform football before the numerous changes that came in 1906. As would be the case with the rules changes of 1906, some 1903 rules changes proved of value and remain part of the game today, while others did not have their intended effect and disappeared from the game.

Football Archaeology is reader-supported. Click here to buy one of my books or otherwise support the site.

Looks like the Polo Grounds' basefield infield had been sodded, which is about 20 years earlier than I had previously seen that done on any football field. Might be a good topic for your site.