The SATC, Spanish Flu, and College Football in 1918

As the 1918 college football season approached, it appeared like any other, except that America was at war and some young men that otherwise would have been on campus were fighting in France or were in training expecting to ship there in the near future. With the Allies expecting the war to last until 1920 or 1921, the U.S. Army projected the need to train 6,000 new officers per month moving forward. To encourage college men to remain in school and gain the technical skills needed by a modern army, the Army instituted the Student Army Training Corps (SATC). Conceived as a voluntary program in which colleges joined the program and then took student volunteers, the SATC paid students' room, board, tuition, and a salary, in exchange for the students wearing Army uniforms, drilling, and supplementing their classes with military studies. However, in late September 1918, the Army made the SATC program mandatory for all able-bodied college men, effectively federalizing male college education across the country.

Days later the SATC announced their daily schedule allowed only one hour per day for athletics and recreation, making football practice difficult. The rules also required SATC men to remain on campus during October except from noon to taps on Saturdays. The limited time off campus meant college football teams could not play games at locations more one or two hours from campus, so colleges cancelled their more distant October games and devised new schedules within a matter of days. Schools west of the Mississippi River were particularly hard hit due to the distances between the colleges. The Missouri Valley Conference, the forerunner of today's Big XII, ultimately cancelled the conference season.

If the SATC ruling did not cause enough issues for schedule makers, a far more devastating problem was in the offing that made the deaths caused by the war seem limited in comparison.

The Spanish Flu

Though epidemiologists have since identified likely precursors, the first documented case of the Spanish Flu occurred at Camp Funston in Kansas when a cook was admitted to the base hospital with influenza symptoms on March 4, 1918. The flu spread across the United States and landed in Brest, France within one month of being reported at Camp Funston. It spread to Allied troops and then jumped over No Man’s Land and roared through the German army. Then it faded away.

But that was only the first wave. The second wave was different than most flu epidemics in that it ferociously struck the healthiest members of society: those between 20 and 40 years of age whose immune systems were at the height of effectiveness. Victims bled from their ears, eyes, and nose; were sensitive to the touch and wracked with pain; became delusional; and most frightening to many, suffered from cyanosis, a condition in which their bodies turned blue or purple from oxygen deprivation. Some hospital workers became infected, collapsed at their stations, and were dead within twelve hours. Other patients lasted weeks before dying or recovering. There was little the medical community could do other than provide basic care and comfort. They simply did not have the tools to combat the influenza.

As the second wave of the flu crawled across the country, city and state health authorities' only weapons were quarantines and the banning of public assemblies, including college football games. Each week, teams waited in the hope that their rearranged games might be cleared to play, only to have one after another game cancelled. Like many teams, Michigan opened the season on October 5 and did not play again until November 9. They were lucky to play five games that season. Pitt, the reigning national camp, played their first of five games on November 9. Harvard played only three games. Indiana played four. Some schools canceled their seasons altogether. Games at Penn, Wisconsin, and Nebraska moved forward on October 26, 1918 only by banning spectators and playing in empty stadiums. A number of other games were played without crowds that season as well.

As October came to a close, new cases of the influenza became less common and the second wave of the flu faded away just like the first. Life and football schedules returned to normal, but the Spanish Flu had devastated the country. It took the lives of one in sixty-seven soldiers in the U.S. Army and it did so in a ten-week period. Fifteen times as many civilians died as did soldiers. The influenza accounted for the death of 675,000 Americans at a time the U.S. population was less than one third its current size. Due to the number of deaths and the high number of younger people who died, the influenza epidemic depressed the average American life expectancy by more than ten years. Globally, it is estimated to have killed 50 to 100 million people, second only to the Black Death of the Middle Ages.

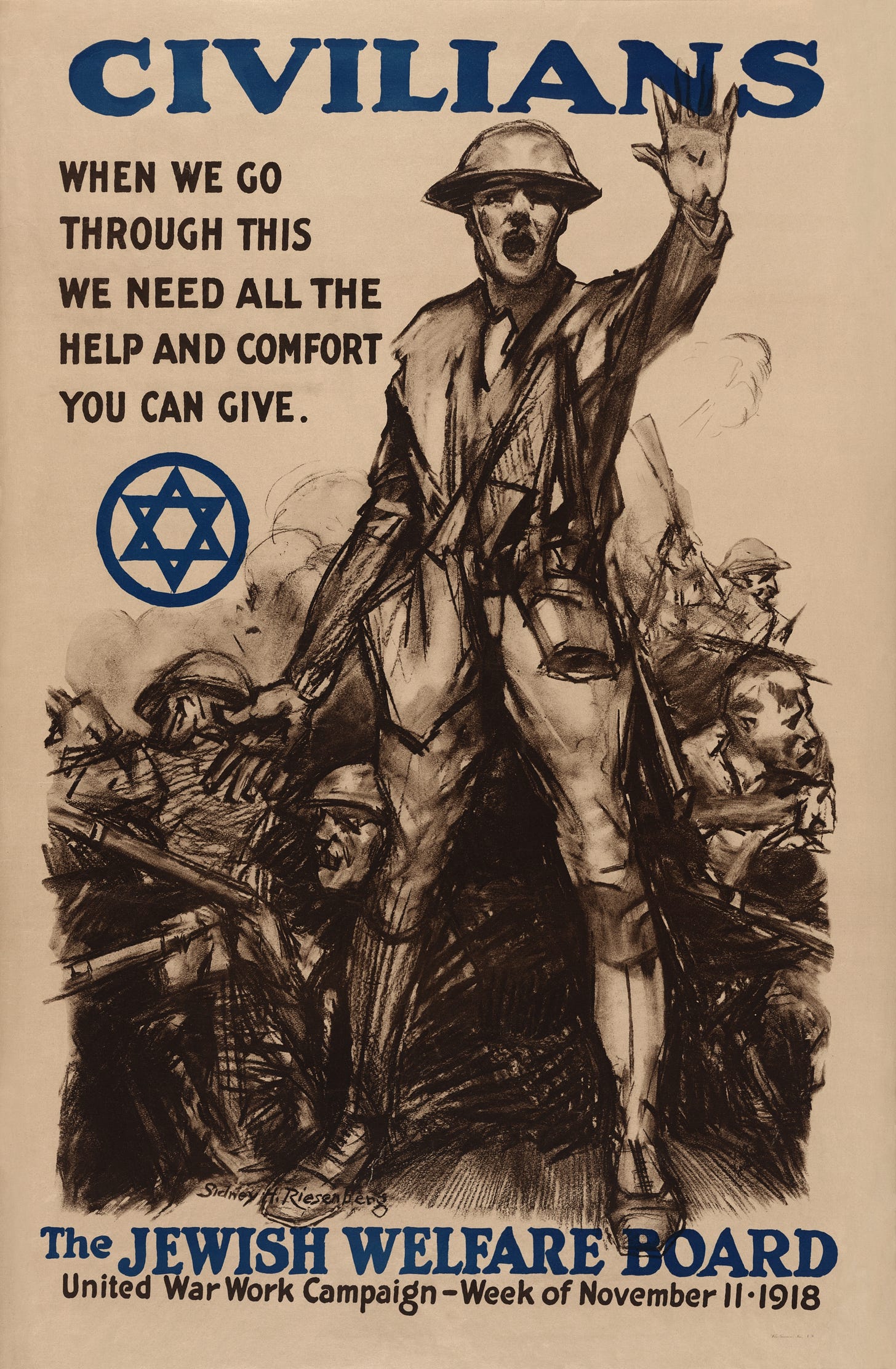

When the war ended on November 11, college football tried to return to normal conditions, but conditions remained different. Since most American troops saw combat only during the last two months of the war, the preponderance of American casualties occurred during that period. Due to slower notification processes of the time, word of servicemen lost in combat or to the flu reached family, friends, and campus communities throughout November. Newspapers printed long casualty lists and their sports pages cited the loss of many college athletes, casting a pall on the games being played.

The 1918 season also differed from most in that several of the country's top teams were from military camps, not the colleges. As a result, the 1918 season ended with two military teams -Great Lakes Naval and the Mare Island Marines- meeting in the Rose Bowl on New Year's Day 1919.

It was a year unlike any other and one that is little remembered today.

Click here for options on how to support this site beyond a free subscription.