The Carlinville-Taylorville Scandal Of 1921

Under ordinary circumstances, America would not pay attention to a football game played the Sunday after Thanksgiving between Carlinville and Taylorville, Illinois, but the 1921 Carlinville-Taylorville game was extraordinary. Sitting forty-four miles apart, each town had fewer than 6,000 residents, and their semi-pro football teams had become rivals, with Carlinville winning at home 10-7 in 1920.

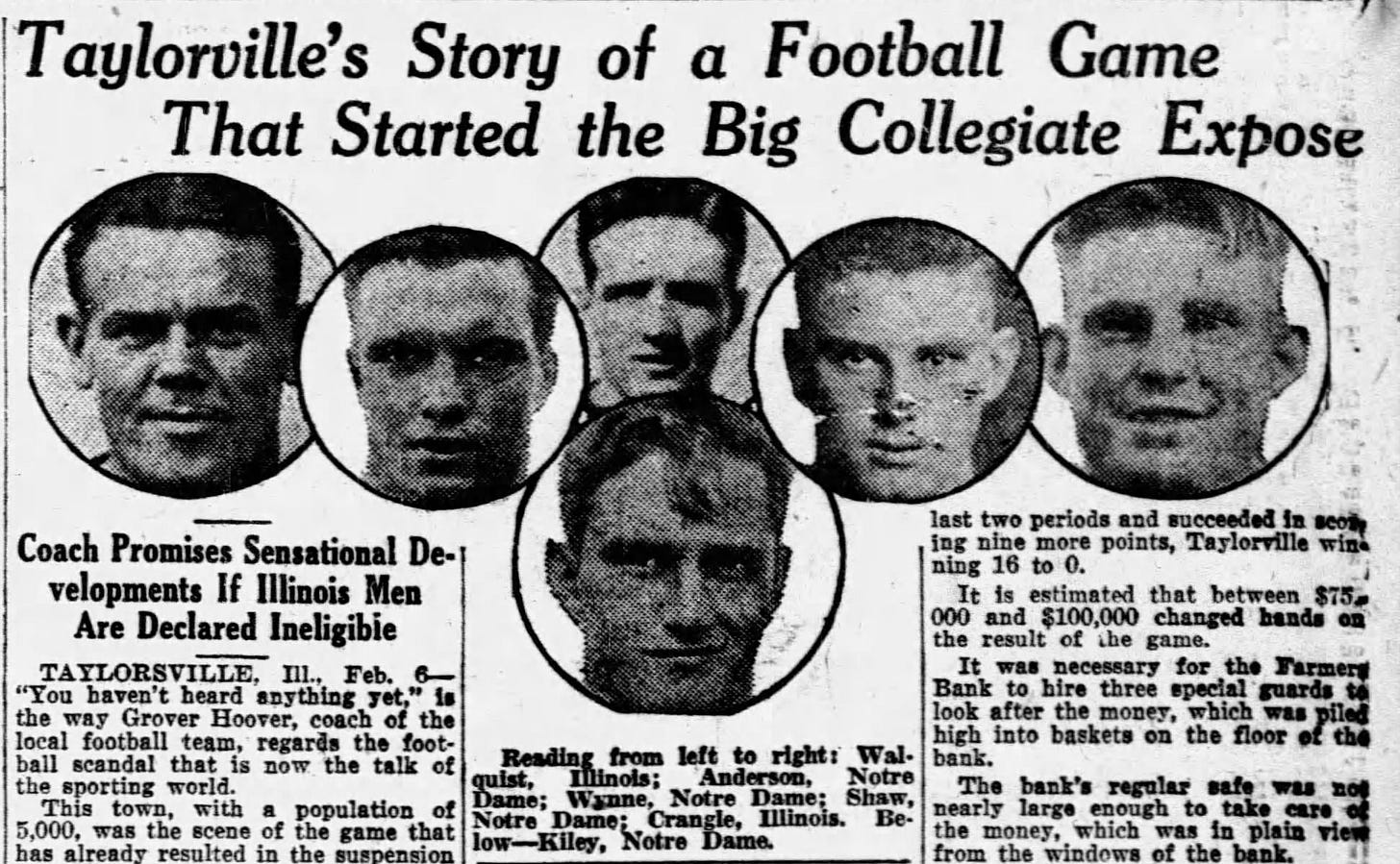

The teams were scheduled to battle again in 1921, and like the prognostications in regional newspapers, everything about the game appeared normal. The day after the game, the Decatur newspapers mentioned 3,000 to 4,000 fans attending Taylorville’s 16-0 win but described a run-of-the-mill game otherwise.

In hindsight, only one line stands out:

“The lineup of each team was almost entirely changed after the half.”

'Taylorville Wins Annual Battle From Carlinville,' Decatur Daily Review, November 28, 1921.

That line took on significance two months later when reports leaked that each town had bet heavily on the game and engaged the services of college football players to ensure they won those bets.

The whole thing started when the enterprising citizens of Carlinville developed a scheme to ensure a repeat victory in the big game. A local lad, Dick Seyfrit, was a substitute end on the Notre Dame team that finished the 1921 season 10-1, and he presumably was the conduit for engaging a group of Notre Dame players to travel to Central Illinois a few days before the contest.

The cone of silence was soon shattered as word spread, encouraging many Carvlinvillians to bet heavily on the game's outcome. Soon enough, word of these goings-ons reached Taylorville and the ears of Dick Simpson, a local grocer and the center-kicker of the Taylorville team. Simpson's younger brother, Dope, played for Illinois, so that connection allowed them to borrow members of the Fighting Illini's 3-4 team to counter the Notre Dame ringers.

The betting total reached $75,000 to $100,000 by game time, so the game's outcome, whatever it might be, would lead to more than the usual celebration or dismay in the respective towns.

Gameday arrived, and everything appeared normal as both teams played their regulars in the relatively uneventful first half. The only plays of note came when Taylorville blocked a Carlinville punt, grabbed the loose ball, and ran it inside Carlinville’s 5-yard line. A touchdown by Carl Dresser, a fine athlete, and AAA baseball player, and an extra point by Simpson the Grocer gave Taylorville a 7-0 halftime lead.

The start of the second half saw Carlinville spring their surprise on Taylorville when their ringer lineup, who had been hiding elsewhere, stepped onto the field. Of course, Carlinville's joy quickly subsided when Taylorville countered with their own set of ringers, including one of the Midwest's top quarterbacks. As in the first half, the ringer teams played a relatively even game, though Taylorville kicked three field goals, which the box score credited to Simpson, though later reports suggest that Joey Sternaman, Illinois' quarterback, actually made those kicks.

Following their 16-0 win, Taylorville was a happy town on Sunday and even more pleased in the days that followed as the local bank's safe overflowed with cash, requiring them to hire extra security guards for the overflowing cash. Despite how quickly word of the scheme spread before the game and the thousands of gameday witnesses, the story of the hired hands remained local until late January when the news broke, and the scheme became a nationwide scandal.

Notre Dame and Illinois launched investigations. While both schools found the players had not been paid for playing, participating in a semi-pro game violated their amateur standing, so all involved became ineligible for further competition at their schools.

Both schools lost players whose football eligibility had ended a few days before they became ringers, though several ringers were multi-sport stars who could no longer participate in basketball and track.

The players ruled ineligible by Notre Dame included:

Eddie Anderson, 1921 football captain, and All American

Chester Wynne, All-conference fullback and track captain

Roger Kiley, varsity end, basketball captain, and track athlete

Lawrence Shaw, varsity tackle and conference shot put champion

Harry Mehre, substitute center, and 1921 basketball captain

Robert Phelan, substitute fullback

Earl Walsh, substitute back

Dick Seyfrit, substitute end, Carlinville resident, played in the NFL in 1923 and 1924.

Illinois lost nine players, including:

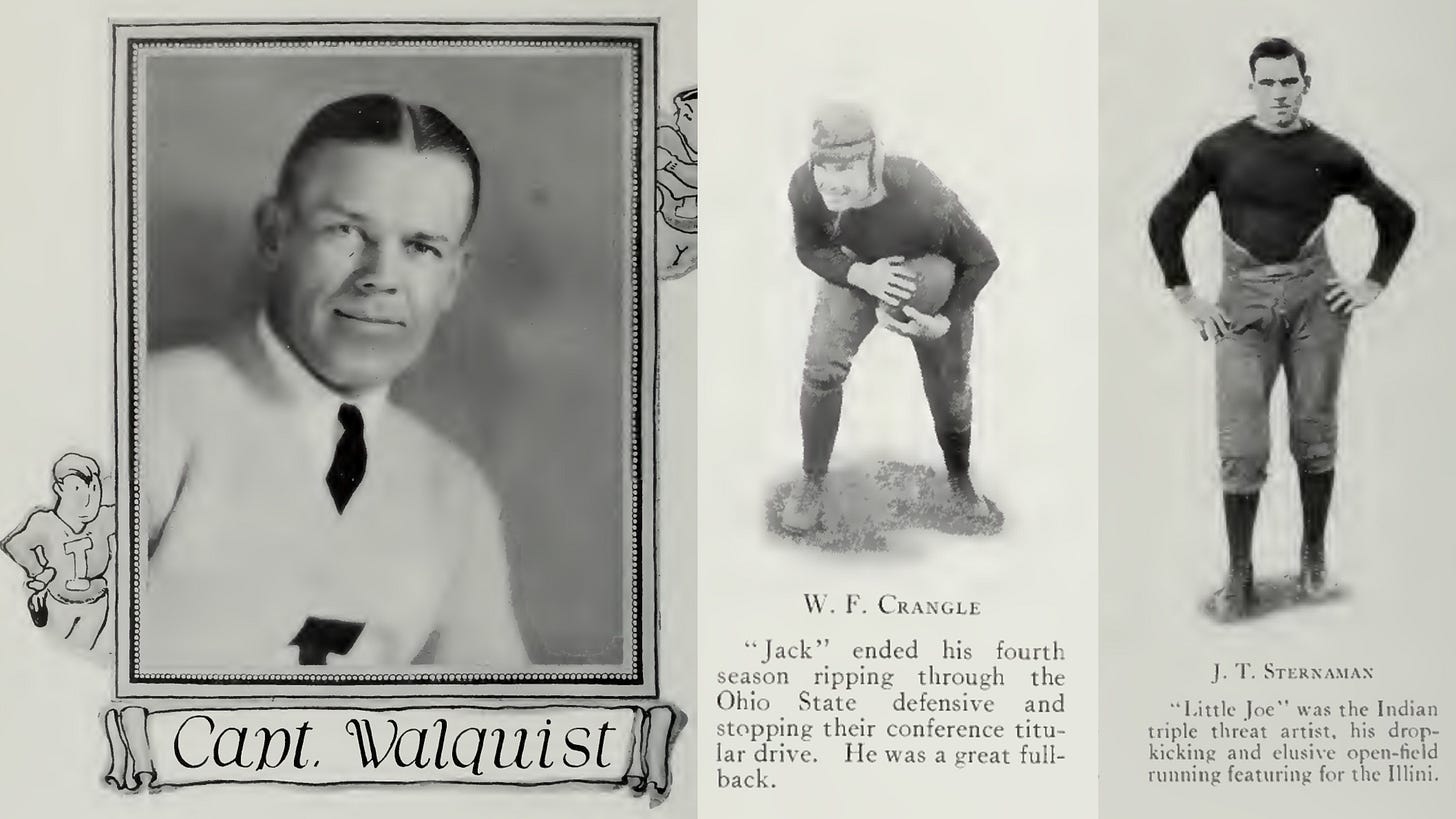

Larry Walquist, halfback and senior captain

Jack Crangle, fullback

Joey Sternaman, a quarterback with remaining eligibility, got an earlier-than-planned start to his 8-year NFL career in 1922

Six others, though only one or two were potential future starters.

That was the end of the story until the next season when it became known that A. L. Augur, Illinois' starting right tackle, played for Taylorville the week before the scandalous Carlinville game, leading to his banishment from the Illini team. Likewise, Wisconsin's starting tackle, Jab Murry, was found to have played in the Carlinville game. Murry, who lived in Taylorville and was not enrolled in school at the time of the game, had also violated his amateur status by participating.

Following the scandal, college coaches and administrators issued public statements describing professionalism's perils and predicting the ruin of football as they knew it, leading the American Professional Football Association, soon to be called the NFL, to take action. Since the league had a policy against league members signing or using players with remaining college eligibility, they took action by stripping the Green Bay Packers of their franchise when the Packers admitted using three Notre Dame players in a game in Milwaukee. (The three Notre Dame players who played for Green Bay were not among the Carlinville eight.)

Despite all the turmoil, the football world quickly moved on from the scandal. The Packers were readmitted to the NFL a month or two later, allowing them to continue without harm. Red Grange's appearance on the Illinois varsity in 1923 helped them forget their shameful episode. Likewise, Notre Dame's 1924 national championship season made Irish eyes smile once again.

In the end, the Carlinville-Taylorville scandal was much ado about nothing. Many recruiting and payola scandals followed, and it would be another century before the college football world accepted that their players could be professionals and be paid for their notoriety, if not a share of the gate.

Football Archaeology is reader-supported. Click here to buy one of my books or otherwise support the site.

Anderson and Shaw were hardly hurt by having this incident on their permanent records. Both became fabled coaches, with Shaw winning the NFL title with the Eagles in 1960, and Anderson coaching Heisman winner Nile Kinnick at Iowa.