The Wretched Field Conditions of Football's Past - In Pictures

Wretched field conditions were a regular feature of football games in the past. They significantly affected play, particularly as the season wore on, with muddy conditions one week starting a cycle of deteriorating conditions. Field conditions began to improve as schools built or upgraded their stadiums in the 1920s and 1930s because they often enhanced the infrastructure underlying the fields, besides expanding the stadium seating capacity.

Field conditions in football's earliest days were primitive, like the game itself. Games were played on almost any available open field such as college greens or pastures on the town's edge. As time marched on, schools began playing at major or minor league baseball parks whose grandstands could hold large crowds, but whose dirt infields became part of the gridiron. In addition, many schools built multi-purpose stadiums to handle football, baseball, and track.

Having outlined the broad reasons why field conditions were more suspect in the past, let's turn to images of those field conditions. The images shown below were identified during a review of more than 2,000 college yearbooks published between 1900 to 1925. (Pre-1910 yearbooks often included only a single, posed image of the year's team. Game action photos became more common after 1910, though many were photographically challenged.)

Mowing the Field

The neatly manicured lawns of the English estates we see in movies set in the 18th or 19th century were not as neat as portrayed since they were maintained by grazing, hand clipping, or scything the lawns. The reel mover did not arrive until the 1830s, and the first internal combustion-powered mover only came to the U.S. in 1919. The well-trimmed grass football fields we know today did not exist for much of football's history. Not only was it difficult to keep the grass trimmed, but allowing it to grow longer helped the grass withstand the abuse of daily practices and games.

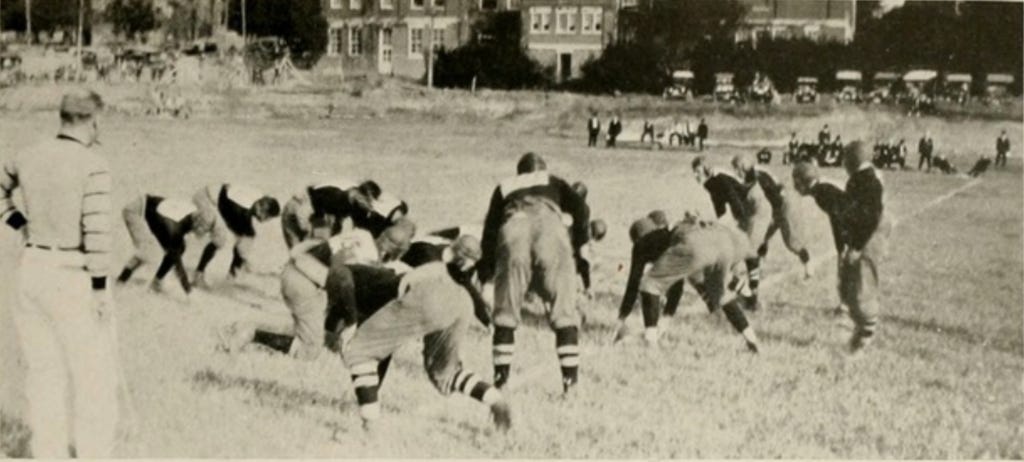

Dirt and Dusty Fields

While the grass on football fields grew long in some locations, it barely grew elsewhere. Before the massive flood control, water routing, and hydroelectric programs of the 1930s, large swaths of America's arid West did not water their football fields. Moreover, the local soils were unfriendly to grasses common to the North and Midwest. The combination resulted in dusty and hard-packed fields that some period writers described as hard as adobe. Spreading sawdust on the fields was the preferred method of enhancing the soil and making fields softer.

While dusty and cement-like fields were more common in the West, similar conditions existed in the Midwest and East, particularly on fields that dried out after hosting several muddy games. Dusty conditions at Penn State in 1908 impeded the team's ability to practice effectively: "Practice at State College was not as satisfactory as expected owing to the dry and dusty condition of the field. Dust choked the men so that continuous scrimmage work was impossible. The squad was worked in shifts of five or ten minutes so as to give the men a breathing spell."

Grass fields are watered via sprinkler systems today, but it was not until the 1930s that the impact sprinkler head was invented. One workaround was to have local fire departments use their pumper trucks to water fields in the days leading up to big games.

The rules barring the use of kicking tees testify to the poor condition of football fields. College football allowed artificial kicking tees for the first time in 1944. Until then, kickers had teammates hold the ball, or the kickers built tees by gathering dirt and sod and placing the football on the dirt mound. The fact that dirt and clods of grass were available in the quantities needed to build these mounds tells you everything you need to know about the field conditions at the time.

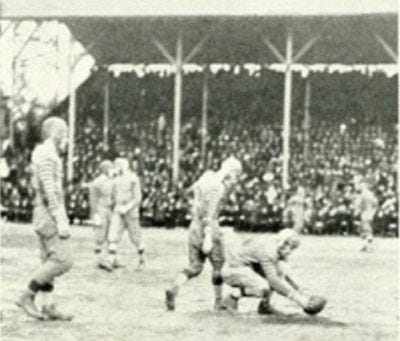

Rain and Mud

In northern climes, fields that became devoid of grass remained suitable for play as the season wore on, despite their unattractiveness.

As schools began building or renovating football stadiums in the 1910s, drainage systems became part of the specifications. The systems were far less sophisticated today, and even the best systems remained problematic, with the pipes becoming clogged and the pumps overworked. The Yale Bowl, which opened in 1914, was an architectural and technical marvel with a top-of-the-line drainage system. Still, the rains that came on the days before the Harvard game that year left the field soggy, requiring a crew of 150 men to spend the night before the game removing water from the field with mops and buckets. Muddy fields with standing water were standard whenever a certain amount of rain fell.

Schools with significant funding took several measures to protect their fields from the cold and rain, including covering the field with canvas or, more often, straw. Both were removed several hours before kickoff, after which workers spread sawdust to soak up the moisture.

Muddy fields impacted play in multiple ways, and the effect was exacerbated by the rules of the time. Although we still talk about the "game ball," teams use numerous footballs during games today. However, through 1921, one football was used the entire game, and the 1922 rule only allowed the referee to replace the ball at halftime. Using one ball the whole game on rainy days made the ball waterlogged, making it harder to throw. The wet ball was more difficult to snap, while punts and placement kicks did not travel as far. Worse, dropkicked field goal attempts were problematic because the ball did not readily bounce off the mud or out of the puddles.

Of course, the muddy ball became slippery, which was one reason teams began using friction strips in the 1910s and 1920s. (Friction strips were canvas or leather strips, ovals, and other shapes sewn in patterns on football jerseys and sleeves to reduce the likelihood of fumbling.)

Field Markings

While the length of grass, absence of grass, and muddy, puddled fields marred play and spectating experience, a less dramatic shortcoming occurred when schools chose to limit the field markings, presumably to save a few bucks on chalk and the labor to apply it.

Even those schools that marked all the yard lines sometimes struggled to properly chalk the lines, either by dropping too much chalk or by failing to apply straight lines.

Summary

Field conditions have become mostly irrelevant to the outcome of today's games that we forget or fail to realize the impact they had on contests in the past. Field conditions also impacted the sport more broadly. Teams built their offenses and defenses under the assumption that one or more games each season would be played in sloppy conditions. That assumption led teams to stress the run game and to play field position football, frequently punting on early downs. Advances in watering and drainage systems, the development of specialty grasses, and the onset of domed stadiums and artificial turf have largely removed the need to make those assumptions, contributing to the game's opening up. Snow is the primary field condition concern today, and the rise of heated fields promises to diminish that threat in the future.

Football Archaeology is reader-supported. Click here to buy one of my books or otherwise support the site.