November 10, 1917: Mare Island vs. Camp Lewis Football

The biggest game of the 1917 football season in the Pacific Northwest was not played by college teams, but featured elevens from the military training camps popping up around the country. Played at Tacoma Stadium, whose 32,000-seat capacity made it the largest stadium on the West Coast at the time, the contest featured the Mare Island Marines and the soldiers from nearby Camp Lewis. After playing one another on November 11, 1917, the teams were meet again in the 1918 Rose Bowl.

Background

After declaring war on April 6, 1917, the U.S. quickly began sending men to training camps across the country. Some camps, like Mare Island, which sits in San Francisco Bay, was the long-time training camp for Marine recruits inducted west of the Mississippi River. The Army, on the other hand, built new camps across the country to train the its millions of enlistees and draftees. Camp Lewis, located outside of Tacoma, was one such camp.

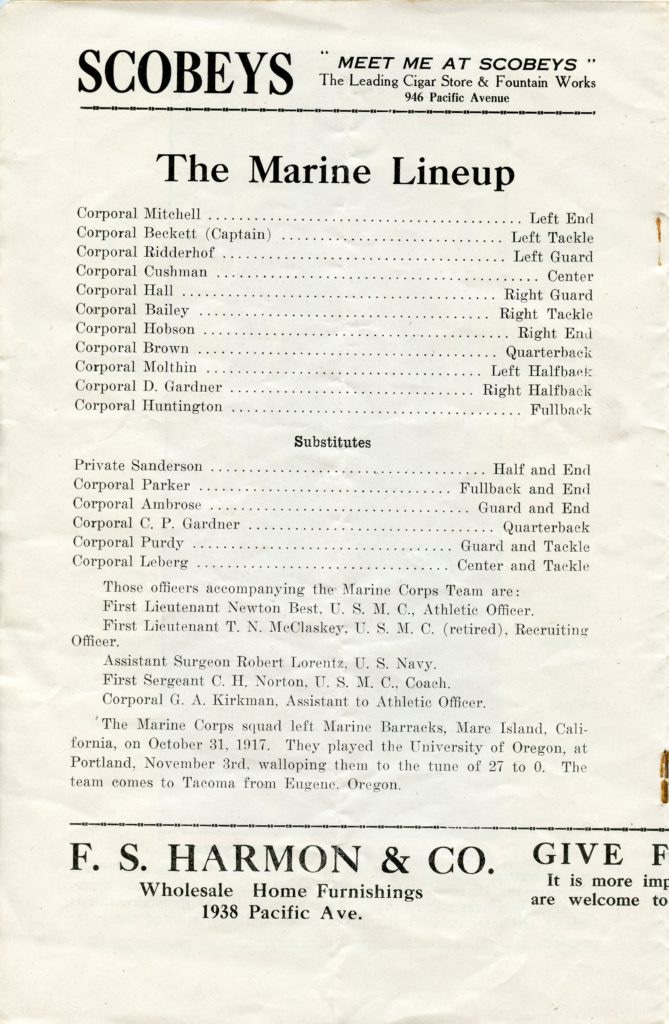

As at most military camps during WWI, Mare Island and Camp Lewis formed football teams that served as recruiting and public relations tools, and as recreation for the men stationed at those bases. Both teams were dominated by former college players. Mare Island began its season in September with two victories over California, followed by October wins over the Olympic Club of San Francisco and St. Mary’s. Their fifth win came in an early November contest with Oregon, the alma mater of five Mare Island players.

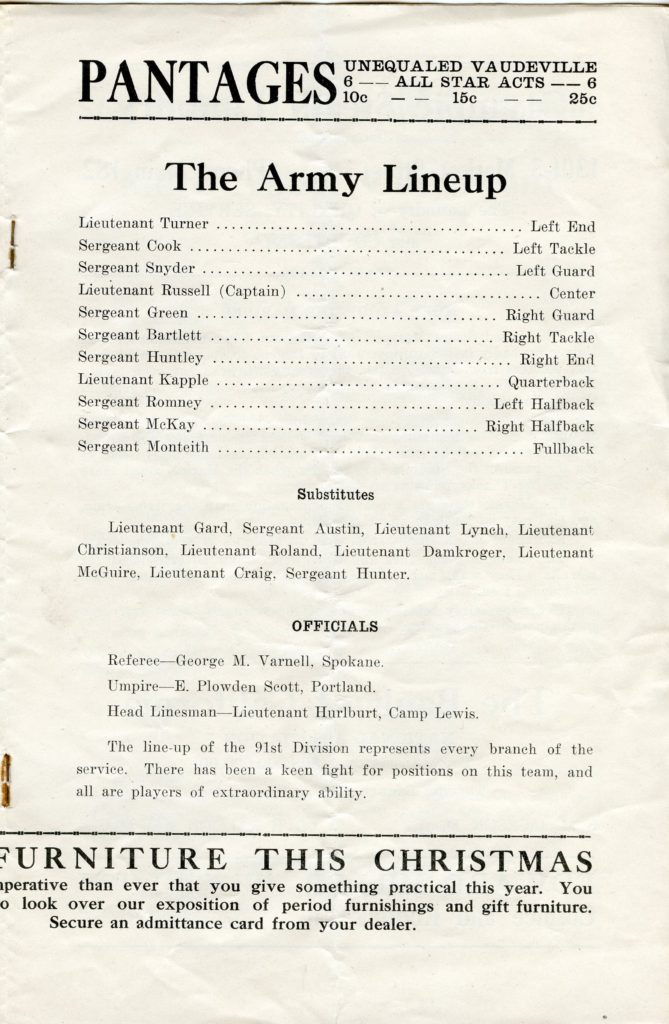

Camp Lewis, on the other hand, got a late start on the season due to the need to build the camp and await a cadre of newly-trained officers. Although teams representing parts of Camp Lewis played games in October, the all-camp team faced only one outside opponent before facing Mare Island. Camp Lewis’ sole victory over the Oregon State freshmen paled in comparison to Mare Island's season record.

Mare Island’s 5-0 start and victories over top college teams led to them being touted as a potential Western representative for the 1918 Rose Bowl. In the week before the game, the Marines, roomed at fraternity houses on the University of Oregon’s campus and spent their days being schooled by Oregon’s football coach, Hugo Bezdek. They were operating on all cylinders entering the game with Camp Lewis. With the game being played during the days of limited substitutions, the Mare Island Marines dressed only seventeen players for the game.

With only one game under its belt, Camp Lewis was an unknown quantity, even to themselves. Camp Lewis had difficulty holding effective practices because their players were spread across multiple regiments and specialties, each of which maintained separate schedules. Their play suffered accordingly, but there was plenty of talent among the twenty players that dressed for the game with the Marines.

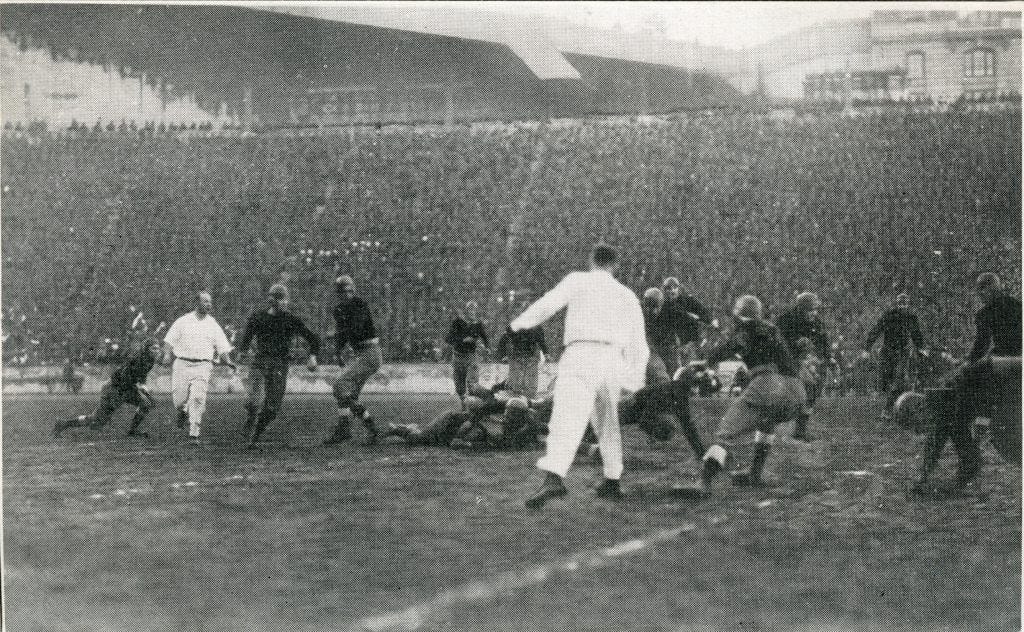

Of the game’s 25,000 attendees, 10,000 were soldiers from Camp Lewis who took the train to Tacoma’s Union Station and then marched in formation to the stadium. Regimental bands played The Star-Spangled Banner, a pre-game tradition at football games that originated only weeks earlier. The game's sixteen-page program profiled the teams and provided the starting lineups, all supported by advertisements for vaudeville acts at the Hippodrome, Cuban cigar shops, and haberdashers specializing in military supplies.

Neither team moved the ball until the second quarter, when Mare Island's Walter Brown popped several solid runs, moving the ball to the two-yard line. Fullback Hollis Huntington powered the ball over the goal line and Fred "Dutch" Molthen converted the extra point to give the Marines a 7-0 lead. Camp Lewis dominated the second quarter with four first downs versus the Marines' one, and drove to the Marines' fifteen-yard line, but could not take it across for a score.

The key play in the second half came on an inadvertent quick snap that surprised Camp Lewis' defense as much as it did Mare Island's quarterback, Walter Brown, but Brown carried the oval for a 27-yard gain to the Army six. Four plays later, Brown took it the last foot into the end zone for the game's final touchdown and score, giving the Marines a 13-0 advantage. It was a clean, well-played game during which neither team was penalized and each completed only one forward pass.

Two weeks later, Mare Island traveled to Los Angeles and beat USC 34-0. Even better, the Rose Bowl Committee invited the Marines to represent the West in the 1918 Rose Bowl game, an invitation the Marines eagerly accepted.

Although the Tournament of Roses Committee wanted Mare Island to play an Eastern representative, several of the top college teams were barred from postseason play by their faculties. The top military teams east of the Rockies beat one another toward the end of the season or were under military order restricting travel. Without a top Eastern team available to travel to Pasadena, the Rose Bowl Committee invited Camp Lewis after they won four straight following their mid-season loss to Mare Island. Mare Island won the 1918 Rose Bowl 10-7. It was the first Rose Bowl featuring two West Coast teams (the other came during WWII) and was the first of five Rose Bowls featuring teams that faced one another during the regular season.

After the 1918 Rose Bowl, the team members returned to their primary tasks: training for the war. Many were subsequently accepted into officer or aviation training and were still in training when the war ended. Twelve of the twenty Camp Lewis players that dressed for the Tacoma game served in France, while only three of the seventeen Marines did so. Camp Lewis' Frank Gard, a substitute end, and Ralph Hurlburt, a Camp Lewis officer who acted as Head Linesman for the game were killed in action during the Meuse-Argonne Offensive. Mare Island's starting quarterback and halfback, Walter Brown and Fred Molthen, completed Marine aviation training, dying in flying accidents during the early 1920s. Four of the five Marine interior linemen (Beckett, Ridderhof, Cushman, and Hall) and a reserve back (Sanderson) spent their careers in the Marines and retired as Brigadier Generals or higher. Each would see battle in time, variously serving in the Banana Wars, against the Japanese in WWII, and against the North Koreans and Chinese on the Korean Peninsula.

Hats off to all those who trained at Mare Island and Camp Lewis during WWI, and to all who have served our country with honor.

Click here for options on how to support this site beyond a free subscription.