Today's Tidbit... 1938 Chicago Bears vs. Negro All-Stars

From its beginning through the 1933 season, the NFL had a handful of Black players peppered across the league's rosters. Never more than a handful, they included stars like Fritz Pollard and Duke Slater, with Pollard even co-coaching two franchises during his playing days. By the 1933 season, the NFL had only two black players: Ray Kemp, a former Duquesne lineman and line coach who played for the Pittsburg Pirates (now Steelers) before being cut after three games, and Joe Lillard, who led the Chicago Cardinals in rushing and passing yards, and points.

In 1934, they were gone, and the NFL did not see its next Black player until 1946. Although Redskins owner George Preston Marshall often gets blamed for the banning, every club in the league complied with the unwritten rule, so they share the blame equally.

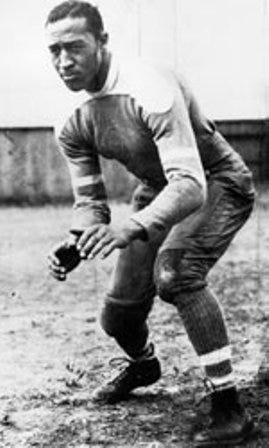

Unable to play in the NFL, Black players of the era competed on predominantly White semi-pro teams and all-Black teams such as the Virginia, New York, and Chicago Black Hawks. The latter teams often barnstormed, playing anyone willing to take them on.

Chicago was home to the Bears and Cardinals in the 1930s, as well as the College All-Star game, the brainchild of Chicago Tribune sports editor Arch Ward. First played in 1933, the College All-Star game attracted at least 74,000 fans each of its first five years as the college stars went 2-1-2 against the previous year's NFL champions.

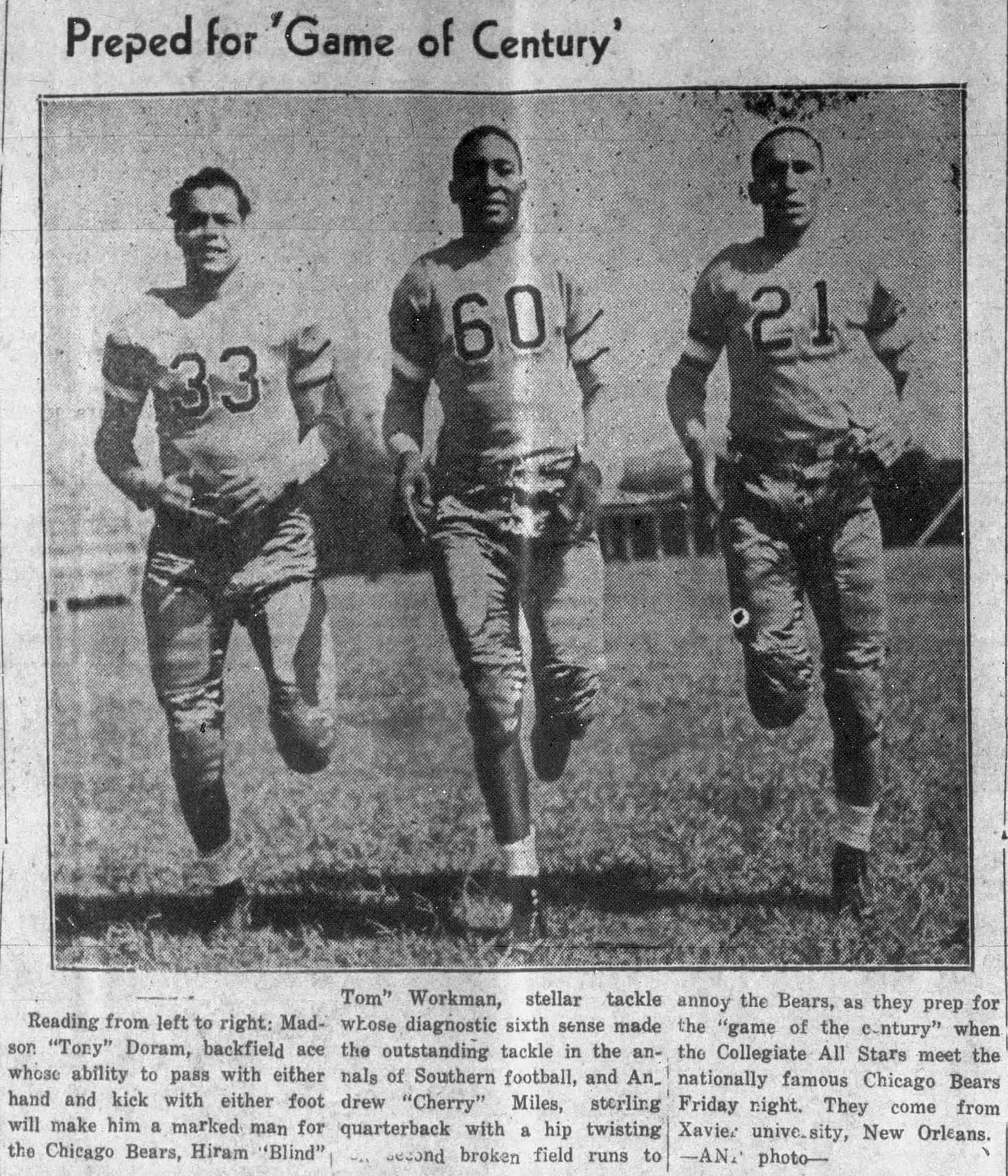

In 1938, not only did the Washington Redskins play and lose to the College All-Stars, but someone with the Tribune came up with the idea for the Chicago Bears to play an all-star team of Black players, touted as the Negro All-Stars. Despite the NFL not allowing Black players in the league itself, the plan for the interracial game moved ahead. The Tribune worked with 100 Black newspapers nationwide to poll their readers to select the All-Stars.

The plan called for Morgan State's E. P. Hunt, the country's top Black college coach, to handle the team along with Duke Slater, Ray Kemp, and Ink Williams, each with NFL experience. However, Hunt proved unable to take the role, so Kemp, the coach at Lincoln University by 1938, took over the job. The team members trained in Chicago for two weeks before the September 23rd Friday night game, with all expenses paid and each receiving $100 in salary.

While the All-Stars began practicing, the Bears were already playing games. NFL schedules in the 1930s were unlike today's because teams scheduled exhibition games to pick up extra bucks before and during the season. Before playing the Negro All-Stars, the Bears had beaten a college all-star team in Providence 24-14 and a southern all-star squad in Birmingham, winning 32-18. They also beat the Chicago Cardinals and Green Bay Packers in regular season contests.

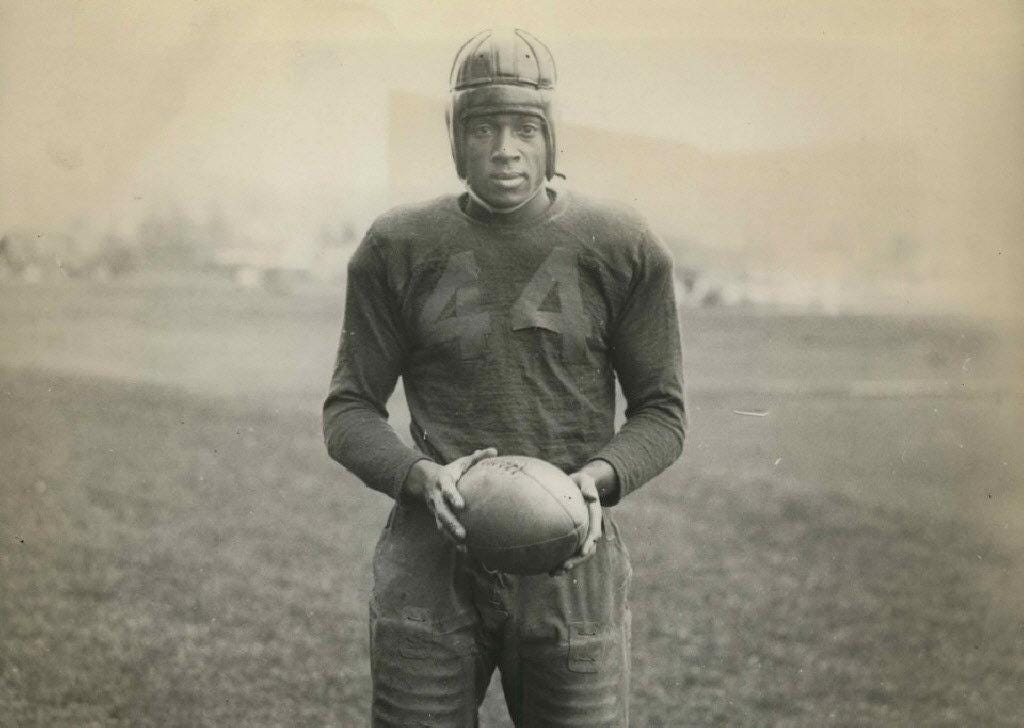

A week before the game, the All-Star coaches named a preliminary starting lineup that included a mix of players from HBCUs and predominantly White colleges. However, the starters differed in several cases by game time.

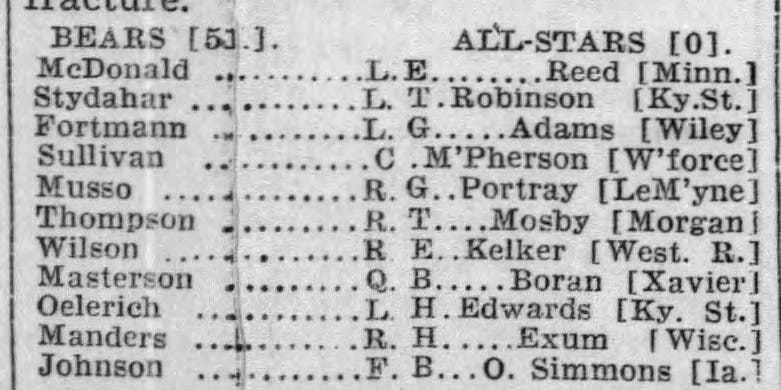

Left end: Dwight Reed, Minnesota

Left tackle: Hiram Workman, Xavier (New Orleans)

Left guard: James Portray, LeMoyne

Center: Richard Sowell, Morgan State

Right guard: Carl Drake, Morgan State

Right tackle: Al Duvalle, Loyola (Los Angeles)

Right end: Doc Kelker, Western Reserve

Quarterback: Madison Doram, Xavier (New Orleans)

Left halfback: Joe Lillard (Oregon)

Fullback: George Edward (Kentucky State)

Right halfback: Ozzie Simmons (Iowa)

On the day of the game, the Chicago Tribune projected an attendance of 30,000, with the expected profits going to several charities. Unfortunately, there was less excitement than expected since only 6,000 showed up at Soldier Field, and even the Tribune provided scant coverage the following day.

The Bears began the game with their starters and easily dominated by running over and around the All-Stars. They inserted backups in the second quarter, and the play became more competitive, but the NFLers continued putting points on the board until the game ended in a 51-0 blowout.

After playing the All-Stars in Chicago on Friday night, the Bears headed to Cincinnati, where they lost to the minor league Bengals 17-13 on the 25th. Then, they took on the independent Los Angeles Bulldogs two days later in Charleston, West Virginia, requiring a 90-yard run in the last minutes to win 14-12. The Bears returned to NFL play after that, finishing the season with a 6-5 record in NFL games.

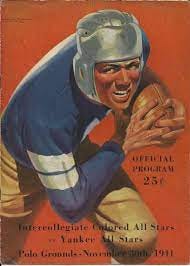

The All-Stars, on the other hand, scattered to the winds. Some returned to their coaching positions, and others to minor league and semi-pro teams. Some of the 1938 Negro All-Stars played for the Intercollegiate Colored All-Stars in 1941 in a game against a team of Northeastern College All-Stars.

Perhaps similar games occurred against NFL teams or other White All-Star teams, but none provided the opportunity to make the money doled out to those playing in the NFL. That started changing in 1946 when the NFL reintegrated but did not gather significant steam until the 1960s when the AFL's Kansas City Chiefs scouting and pursuit of HBCU players shifted the dynamic. The same period saw Black players gain greater access to football programs at colleges and universities nationwide, providing increased access to the NFL.

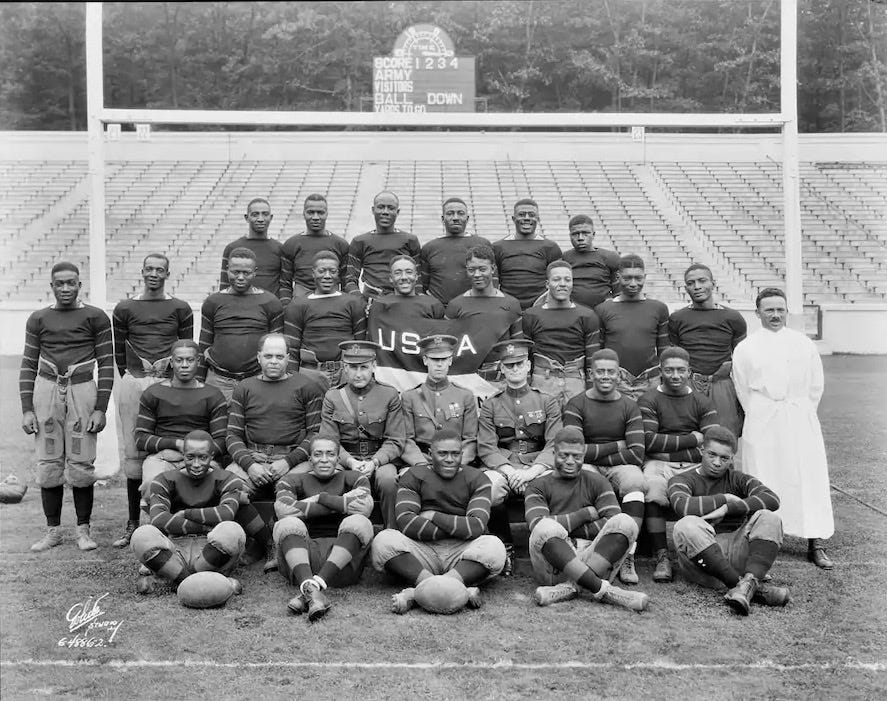

America’s semi-pro and minor-league football teams in the 1920s and 1930s proved more willing than the NFL to play with or against Black players. If you are interested in the topic, I’ve written extensively about the 1920s West Point Cavalry Detachment football teams, comprised of enlisted Buffalo Soldiers stationed at West Point. They are the earliest known Black football team to win a championship in an otherwise all-White league. An introductory article is here.

Football Archaeology is reader-supported. Click here to buy one of my books or otherwise support the site.

Were the Chicago Cardinals the same franchise as the current Arizona Cardinals?

Great background info to set up the game.