Today's Tidbit... Football on Ice

It's easy to take ice for granted, but its ready availability is relatively new in human history. Almost every household today has an electric refrigerator and freezer that automatically dispenses ice or allows us to make it the old-fashioned way, using trays. Likewise, almost every store and gas station that offers beverages also sells bags of crystal clear ice, so ice is widely available to those of us with a cold tooth.

The ancients cut and stored winter ice, and that approach remained the case until early in the 20th century. By then, significant businesses cut ice in northern climes, shipped it in insulated ships to locations closer to the equator, and made lots of money. They also stored it in ice houses in northern areas for use in warmer months.

Machines capable of commercial ice-making arrived before WWI. Mechanically produced ice competed with lake or river ice for several more decades, with much of it devoted to keeping home and commercial ice boxes cool.

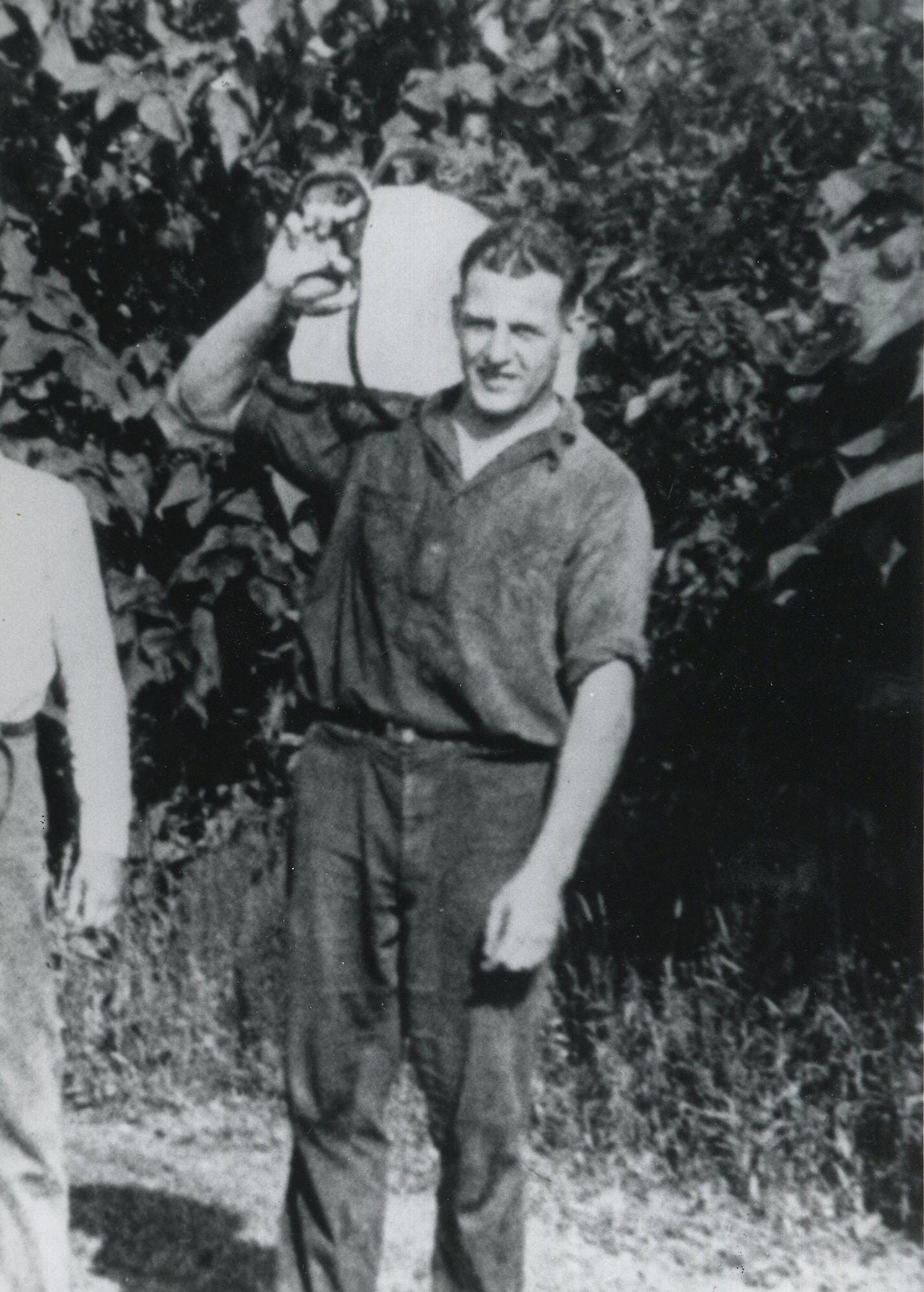

Ice and football have connected on multiple occasions. An important connection came through Red Grange, whose summer high school and college job involved delivering ice in his hometown, Wheaton, Illinois. Grange, who became known as the Wheaton Iceman, retired from the ice delivery business soon after becoming the first athlete to have his number retired.

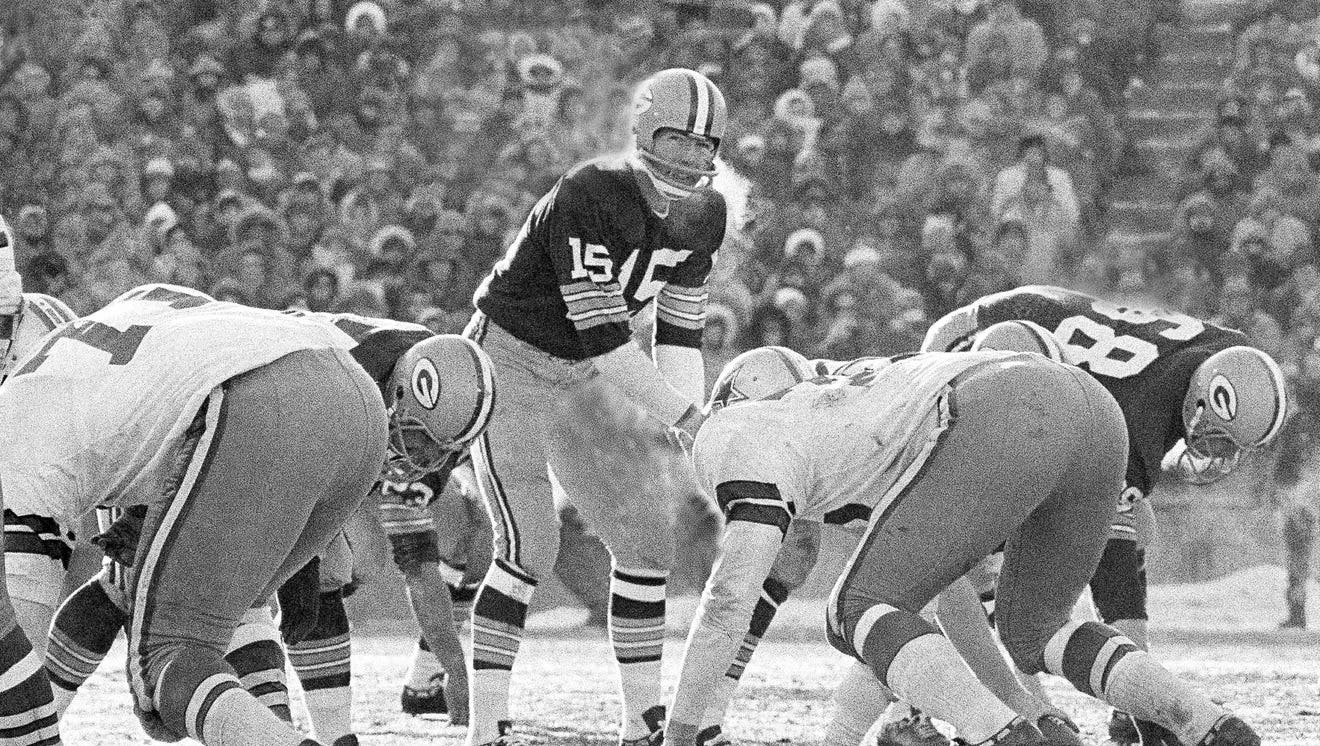

Ice entered football lore a second time when the 1967 NFL Championship game, played on Lambeau Field's frozen tundra, became known as the Ice Bowl.

While both connections were incidental, the primary association of football and ice resulted from ice's therapeutic properties. Physicians had long used ice to cool feverish patients, and athletic trainers joined them in using ice to reduce swelling and ease pain. Physicians used ice packs when Johnny Evers, of Tinker-to-Evers-to-Chance fame, broke his leg in 1910. Ice was a standard treatment for various joint, bone, and swelling injuries among football players in the 1920s through 1950s and is heavily used today.

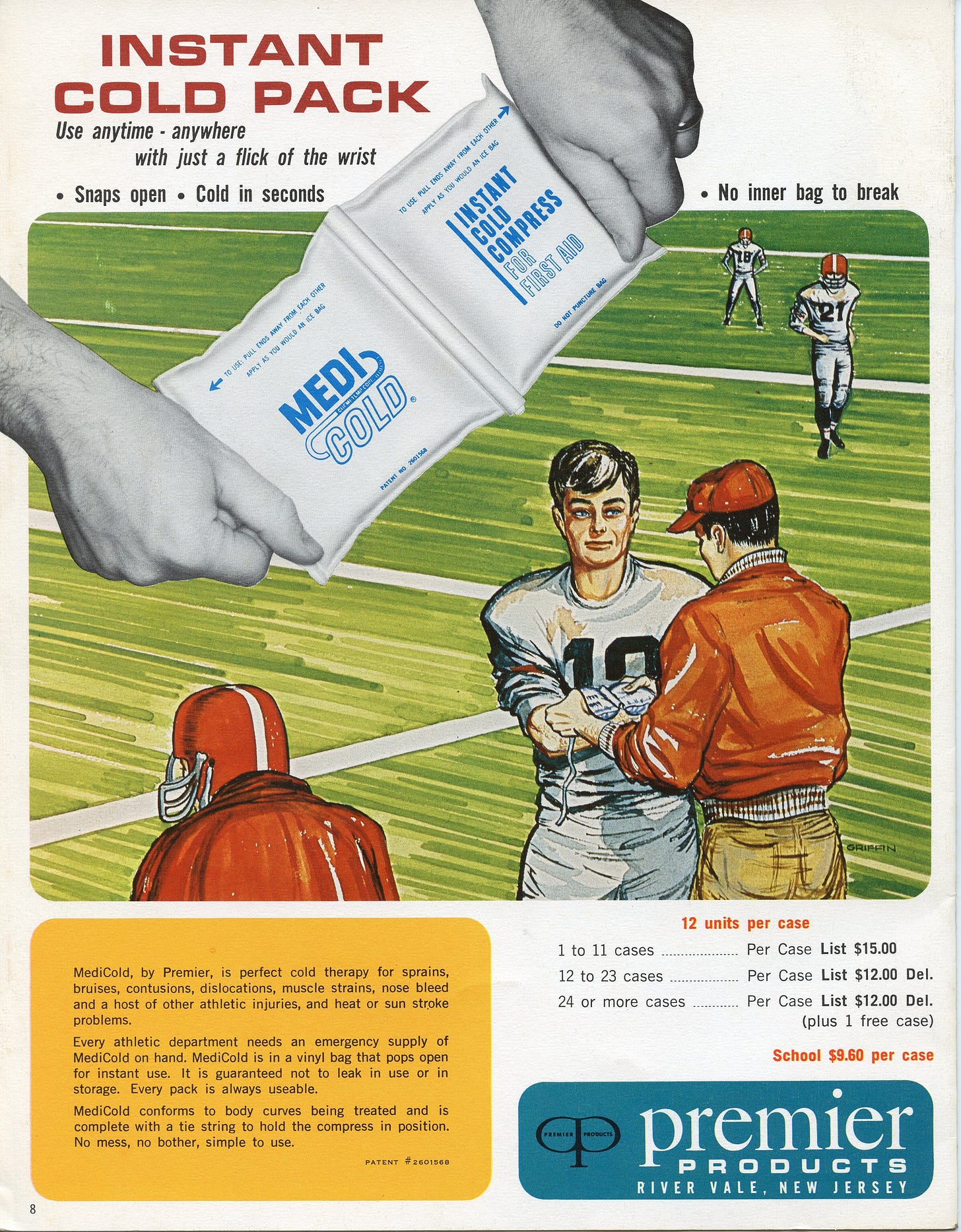

However, one of the challenges with using ice for football injuries was that most injuries occurred on the field, forcing trainers to have ice available on the field should an injury require it. Lots of perfectly good ice sitting on football fields returned to its liquid state while waiting to be used.

That situation changed in 1959 when Albert A. Robbins invented the modern cold pack. Rather than using water, Robbins created a packet within a packet in which previously separated chemicals became ice cold when the chemical solutions became mixed. Initially intended for the food industry, the approach entered the athletic training world a few years later. Chemical cold packs took the training world by storm. They were portable, quick to become cold, convenient, and modern.

However, chemical cole packs were pricey and did not get as cold as the old-fashioned bag of ice. Ice remained or returned to being the preferred solution, especially in the training room where ice was readily available, and the dripping condensation did not cause problems. Gel packs and multiple variations of instant cold packs have entered the market, but trainers give these products the cold shoulder, and ice prevails in most training rooms today.

Football Archaeology is reader-supported. Click here to buy one of my books or otherwise support the site.

I told my wife that my new workout regimen would be the same as Red the "Wheaton Ice Man," but all I got from her was the cold shoulder

Red Grange was an iceman- interesting.