Today's Tidbit... Alternating Sets Of Downs

A Tidbit published a few days ago described how American football transitioned between 1906 and 1912 from requiring teams to gain five yards in three downs to ten yards in four downs. Some prominent coaches argued that teams should gain eight or fifteen yards in four downs, but they adopted the four downs to gain ten yards approach, which remains the rule today.

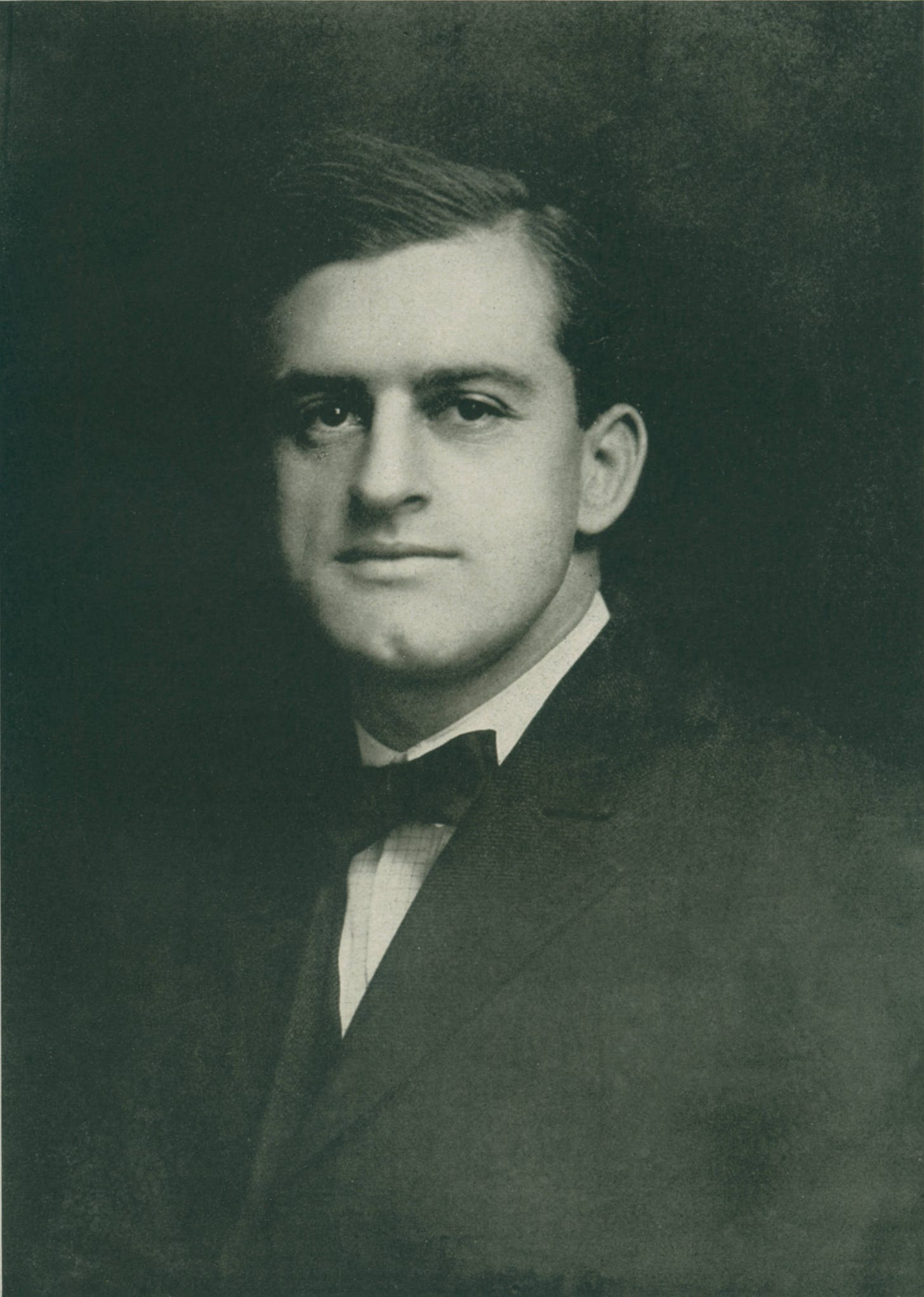

While footballers then argued the merits of various down and distance combinations, Eddie Cochems (pronounced COKE-ems) proposed a different approach. Cochems played football and baseball at Wisconsin when the Badgers went 34-4-1 over four years. After graduating, he coached at North Dakota State, Clemson, St. Louis, and Maine, but it was during his time at St. Louis that Cochems left his mark on football. Cochems devised the first offense that effectively used the forward pass, including throwing the ball using the overhand spiral technique. His 1906 St. Louis team threw the first legal forward pass in college football and went on to an undefeated season, outscoring opponents 407-11.

Besides the frequency of use and throwing technique, Cochems employed pass routes, unlike other teams. Whereas Harvard, Yale, and others tossed the ball high into the air to a receiver encircled by blockers (pass interference did not yet exist), Cochems generally sent multiple receivers downfield running routes approximating button hooks. Interestingly, as the receivers ran downfield, the passer yelled, "Hike," which told the receivers to turn around and look for the ball, foreshadowing the timing routes that emerged decades later.

Cochems thought outside the box and did the same when he rejected the down-and-distance approach, proposing that teams receive alternating sets of downs without a distance requirement. In "Football Unfair in Its Time Element," Cochems argued that football could endlessly tinker with its down-and-distance formula but could not remove the resulting bias that gave stronger teams the ball for greater portions of the game than their opponents.

His solution was to have each team receive alternating sets of five or six downs without a requirement or benefit from gaining yardage other than moving teams toward the opponent's goal line, which was the point of the game. He saw the game being played in 15-minute quarters, but his approach would equalize the number of downs per team, other than difference due to lost fumbles, interceptions, incompletions (which were turnovers at the time), and kicks on early downs. (His approach differed from the 1920s movement to eliminate the clock and allow 40 plays per quarter.)

Cochems also argued for beginning the second half at the spot the first half ended and eliminating the second-half kickoff. He also wanted to remove restrictions on the forward pass, allowing more than one forward pass per play thrown from anywhere on the field. (Now, that would be a wide-open game.)

By 1912, Cochems pushed seven or eight downs per possession rather than five or six. Still, his ideas were not accepted, even when he reiterated the seven downs idea in a 1945 article. (Perhaps the International Brotherhood of Chain Gangs lobbied against the idea.)

The only situation in which Cochems' idea caught on came when football sought ways to settle tie games in playoff situations. The California Interscholastic Federation, for example, instituted a rule in 1926 giving teams an alternating set of five downs to gain as many yards as possible, with the winner being the team earning the most yardage.

Of course, Cochems' alternating sets of downs approach is as arbitrary as the game's current down-and-distance requirement, as the folks north of the border will attest. How the game might have developed differently under the alternating sets approach is unknowable but is fun to think about. His idea of allowing more than one pass per play and at any location on the field was more radical and would produce a dramatically different game, but that is the subject of a future Tidbit.

Football Archaeology is reader-supported. Click here to buy one of my books or otherwise support the site.