Today's Tidbit... Fair Play Before Hash Marks

Since football began, the ball has sometimes gone out of bounds during play, so the game found ways to deal with those events through tactics that changed dramatically over the years. Until 1926, the ball remained live when it went out of bounds, leading to players scrambling for it, knocking over whatever was in the way while pursuing the oblate spheroid.

These days, balls that go out of bounds are returned to the team that last possessed the ball (or last touched it in Canada), with the ball brought back onto the field to a hash mark or inbounds line set at some distance from the sideline. Hashmarks did not enter NCAA and NFL football until 1933, so what procedures did they use to bring the ball back on the field before that?

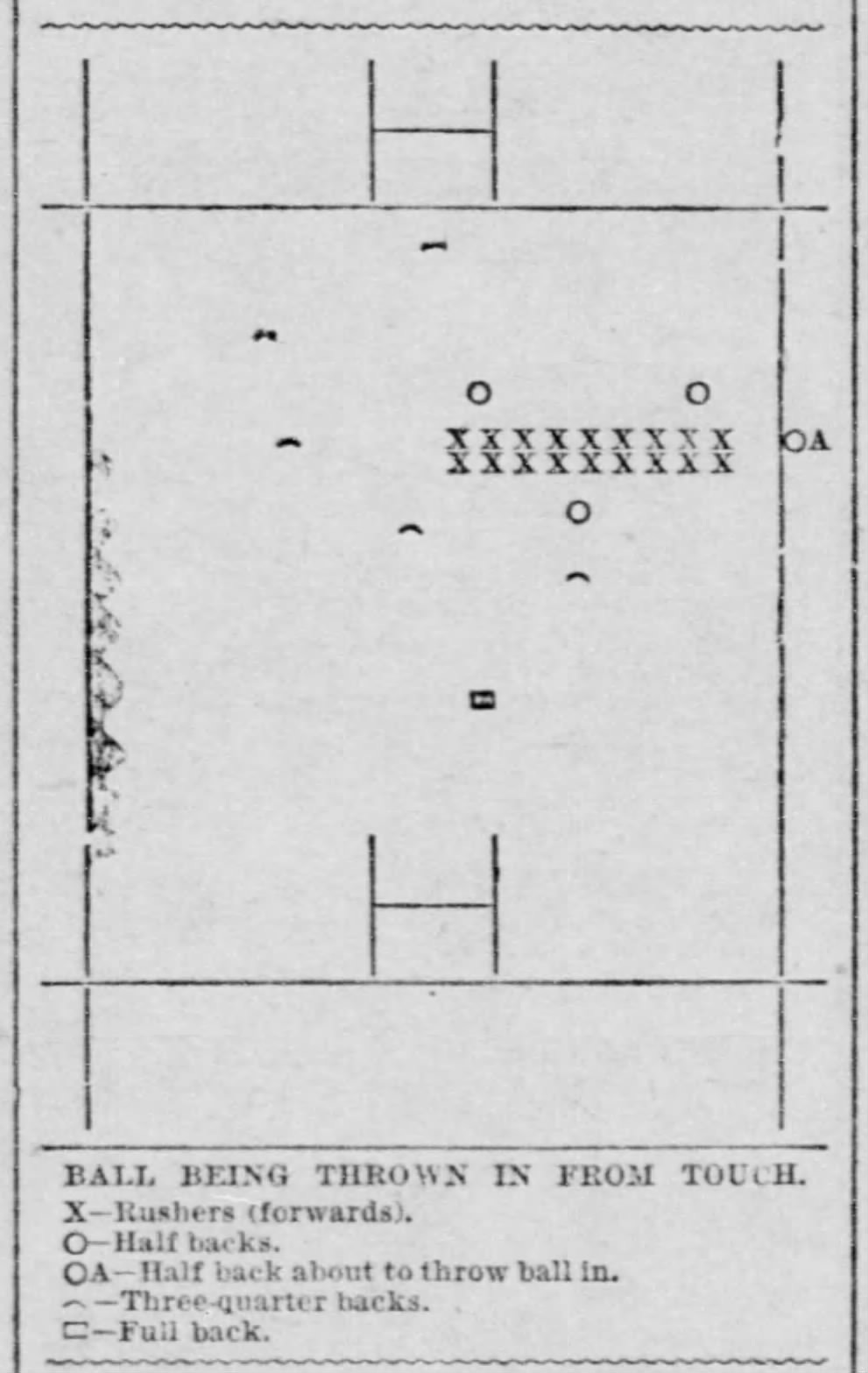

Initially, football teams had five methods to bring the ball back into play from out of bounds. The first method (shown in the illustration) was to throw the ball back to a teammate, who then ran or punted it.

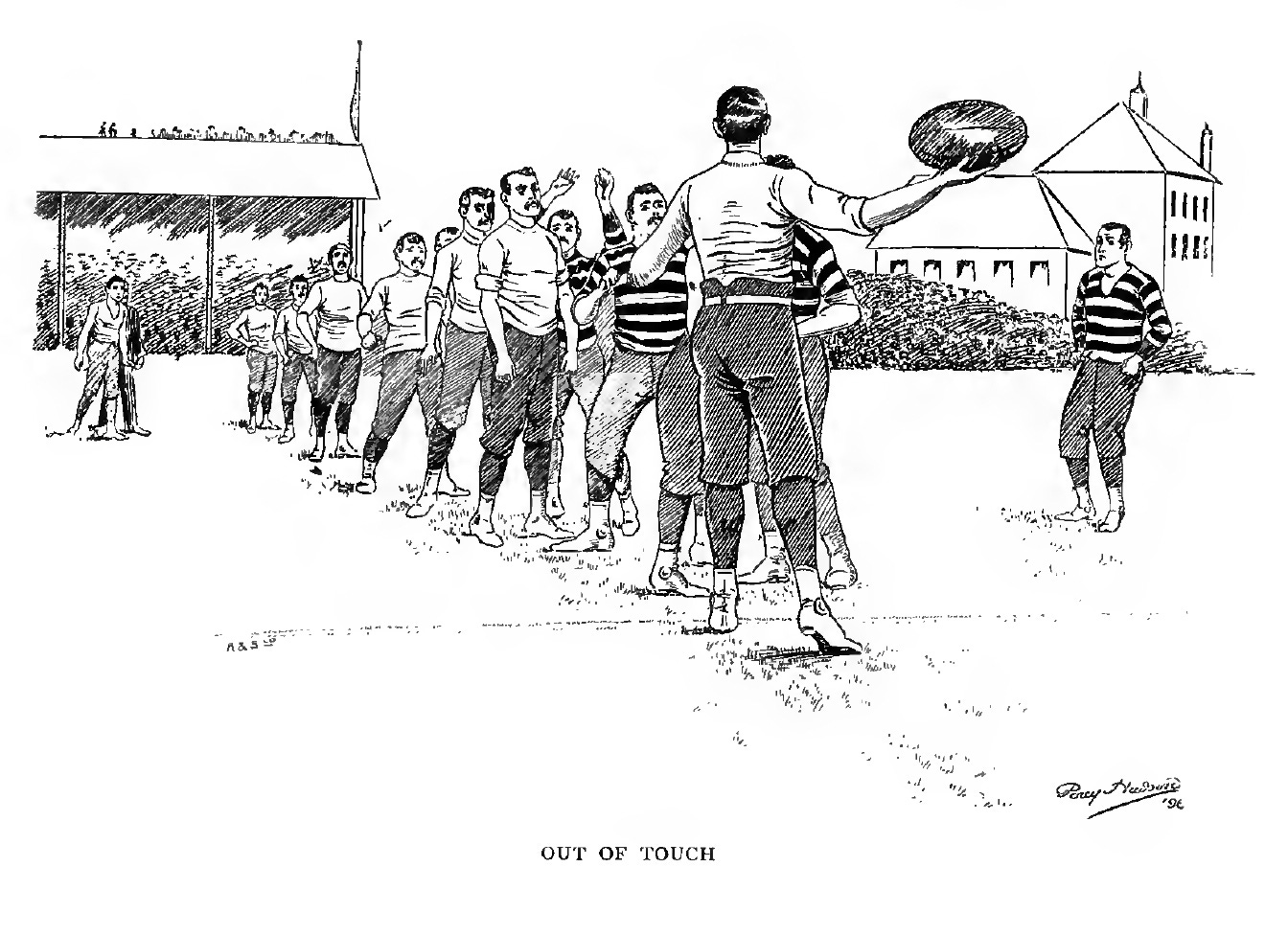

The second option was the "fair," which involved throwing the ball onto the field at a right angle from the sideline and between the two teams lined up across from one another. (The fair or "line out" remains part of rugby today.)

The third option allowed the player to put the ball back into play by touching it down on the field before re-entering the field of play to run with or lateral the ball.

The rule-makers of 1894 eliminated the first three options, leaving us with two approaches. The fourth option, an uncontested punt from out of bounds, was removed from the books in 1904, leaving only one option.

Under the final option, the player could walk the ball five to fifteen yards in from the sideline after announcing how far from the sideline he planned to walk. The offensive team then ran a scrimmage play at the spot where he placed the ball.

Walking the ball back onto the field worked reasonably well, though some team centers insisted that they should do the walking and placing. For many coaches, players, and fans, the problem was not balls that went out of bounds but those that did not. That is, when a play ended one foot, one yard, or five yards in from the sideline, the next play started at that spot, constraining play calling on the next play. It also constrained play calling in the red zone since teams avoided being stuck along the sideline when trying to attempt a field goal.

Of course, the fair and its siblings are long forgotten since the introduction of hash marks 10 yards from the sideline in 1933. Since then, the hash marks have moved closer to the middle of the field, but the underlying logic and process remain the same as football's hash marks continue functioning into their 90th year.

Football Archaeology is a reader-supported site. Click here for options on how to support this site beyond a free subscription.

For those of you who want to see the evolution of hash marks check out this article from last year. https://jamesleegilbert.substack.com/i/135759304/hash-marks

Nice that James doesn't confuse "hash marks" with Lockney Lines. Despite Tim's best efforts, many people still seem to refer to the "Lockney Lines" (invented by my father, John Lockney) as "hash marks."