Today's Tidbit... Football and Graflex Cameras

Football is a lot more than the game played on the field. Among other things, it is also about the technologies that have allowed fans of different eras to experience and develop a love for football, even when unable to sit in the stands to watch a game. Many of our favorite memories come from games we did not attend, and some of our favorite "pseudo-memories" involve images or films of games that occurred before our time. So it makes sense to review certain technologies that have given us the opportunity to see games we did not see in person.

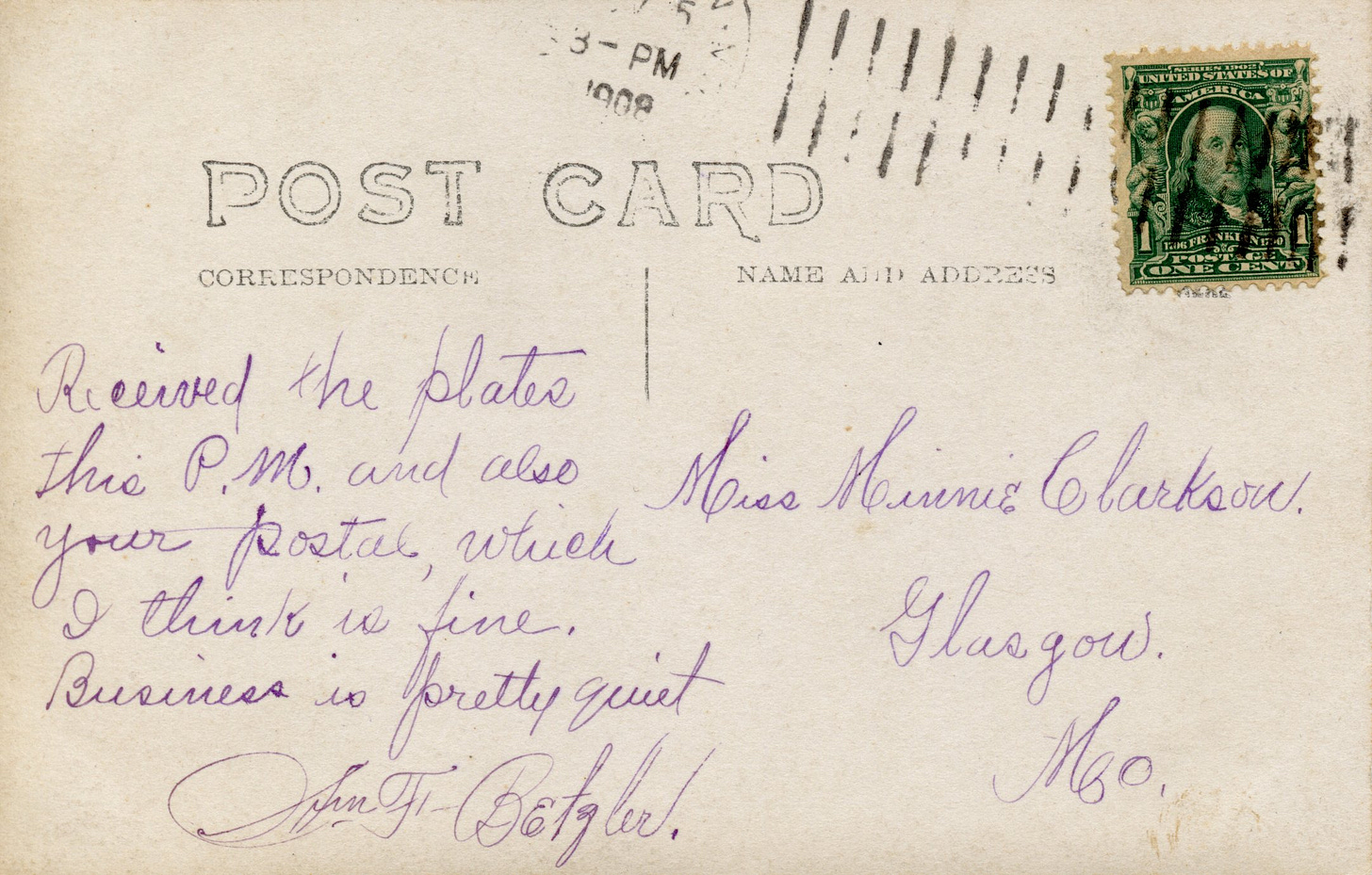

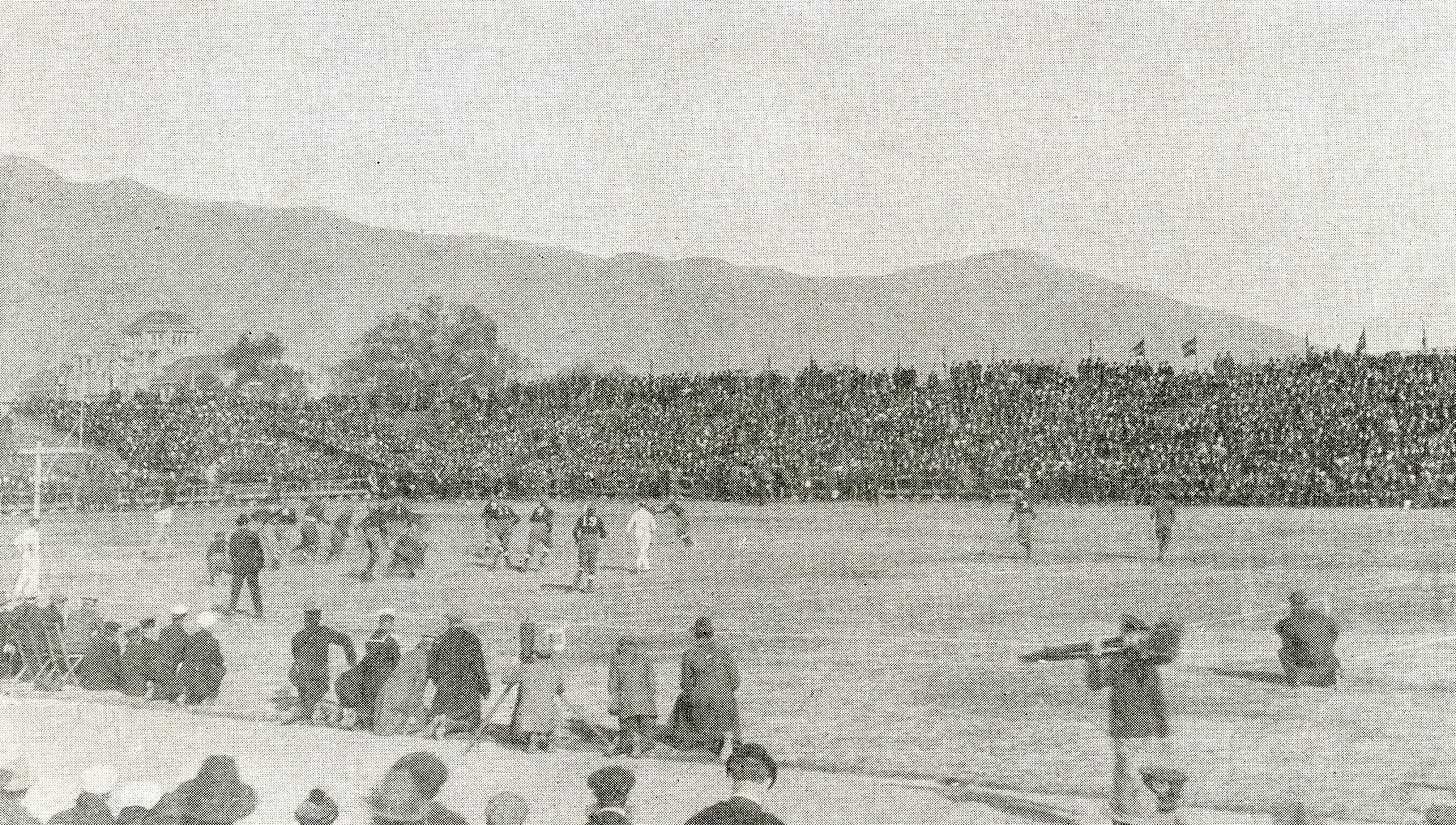

One of those technologies receives a mention on the postcard or RPPC above, which shows nameless Missouri high school teams in 1908. Unlike the era's many posed images of high school teams, it's a game-action image, though it has nothing special to recommend it other than the note written in the upper right, reading:

Taken after 5 o'clock and no sun, with The Graflex Camera.

Much of what we know about football in days gone by comes from books, magazines, and newspapers. We also learn from viewing the period movies and photographs that became increasingly available as photographic technologies advanced.

The scarcity of photographs of local high school games is difficult to grasp today, especially when grandmothers can watch youth, high school, and small college games played a time zone or two away via a simple computer click. New photographic techniques and cameras in 1908 gave folks of that era more access to images than previously available, so it seemed appropriate to figure out what was special about Graflex cameras and why someone might mention it on the front of a 1908 postcard.

As described in previous Tidbits, the first two decades of the 20th century were the high point of the postcard boom. Whether someone hired a photographer or took the picture themselves, they often had the local photography studio print the image on postcard stock. These images were Real Photo Postcards (RPPCs) and were the social media posts of the era.

The back of the postcard shows the RPPC went to Miss Minnie Clarkston of Glasgow, Missouri, a town that sits northwest of Columbia. Period newspapers show she operated a photographic studio there and occasionally attended Missouri photographic conventions. She appears to have relocated to a new town in central Missouri every several years, often buying an existing studio. She purchased her Glasgow studio in 1905. The local news tells us it was burgled in April 1908, after which she purchased a gun before leaving town for Fulton, 70 miles to the southeast, in 1909.

Determining the sender took more sleuthing since half the postmark is missing, making the originating post office unreadable. Deciphering the sender's signature was challenging, but searches for "Betzler" showed that Norma Betzler of Carrollton, MO, attended some of the same photographer's conventions as Miss Minnie. In addition, Norma Betzler's younger brother was William F. Betzler, who ran photo studios in Missouri and Ohio throughout his career. The "Wm. F. Betzler" signature on the RPPC has more flourishes but generally matches the one on William Frederick Betzler's WWI Draft Registration form, so I think we found our man.

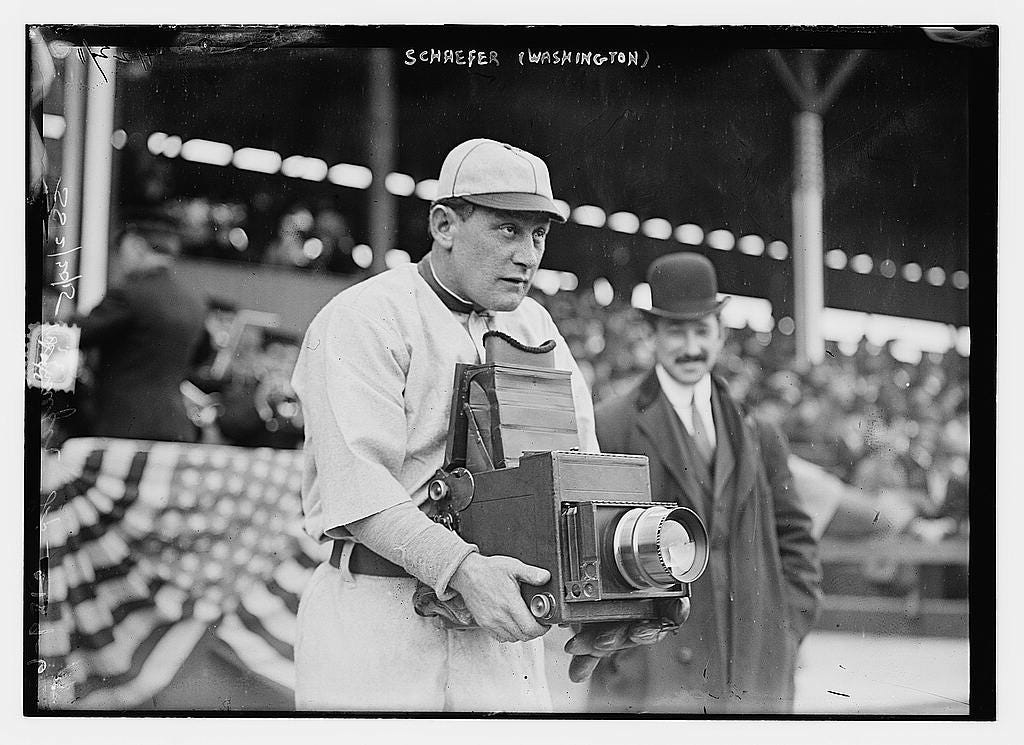

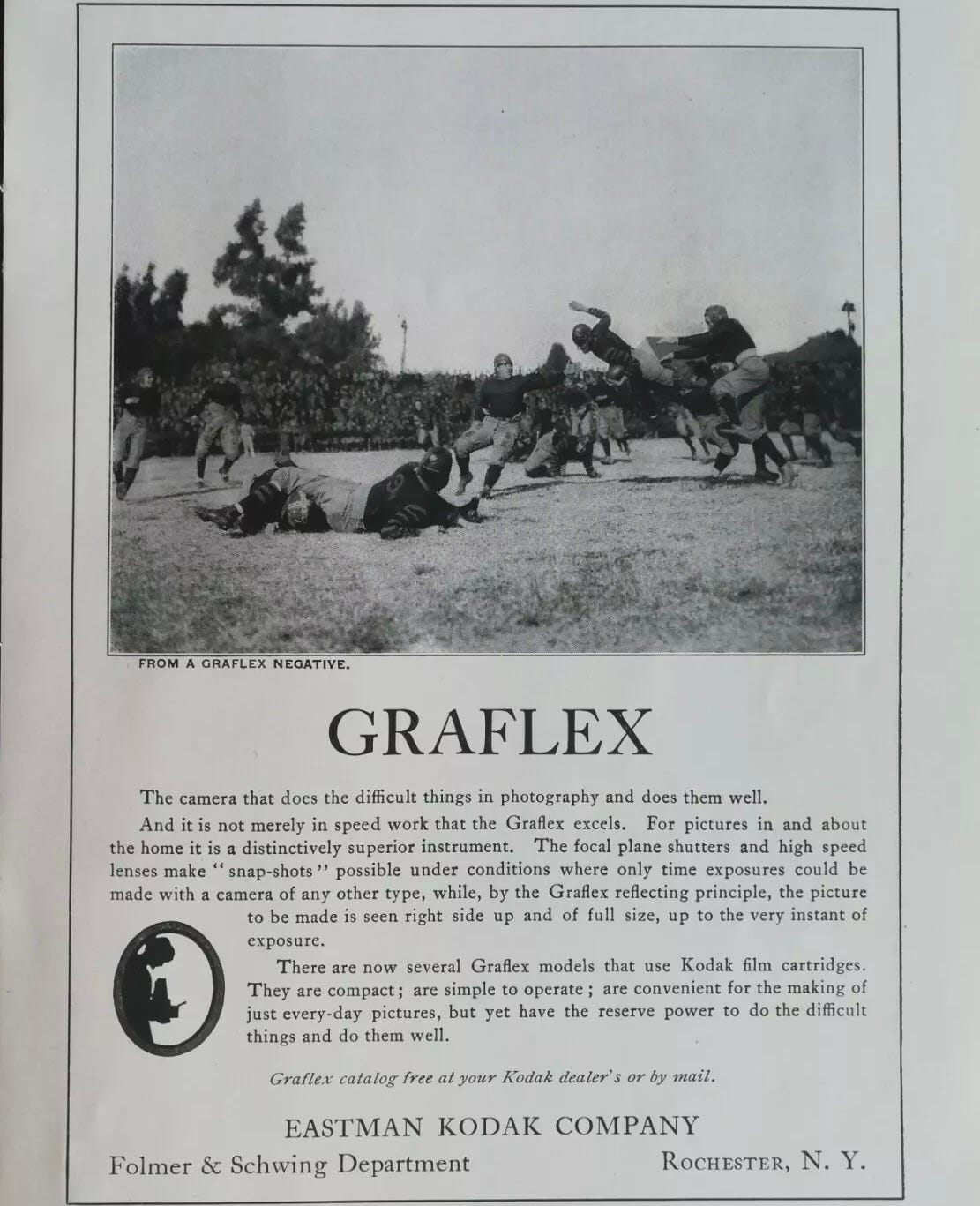

Having identified the sender and addressee, what was the deal with the Graflex camera? I know little about photography, but I learned that Graflex cameras were the standard for photojournalists and many art photographers during the first half of the 20th century. The original model, the Press Graphlex, came out in 1902 or 1907 (sources vary), so it is fair to assume that William Betzler used the Press Graphlex to take the image shown on the RPPC, which means that a small-town photographer shot a small-town high school football game in October or November 1908 using one of the top cameras of the day.

The image and messages show that William Betzler was demonstrating to Miss Minnie that the Graflex could take compelling action photos in low light conditions (after 5 o'clock on a cloudy fall afternoon). The same capability would make the camera valuable for decades for other games and events.

It seems that the Press Graphlex was a highly capable camera. Its wide-angle lens, fast shutter speed, and workings allowed photographers to quickly take a picture upon arriving at a crime scene or moving along a football sideline. In addition, its wooden box and overall construction gave it a sturdiness that worked for photojournalists in the field.

Like most, I was unfamiliar with Graflex cameras until researching this story. However, Graflex cameras likely captured many of our favorite football, baseball, and news images from the first half of the 20th century. So, while this is not your typical football story, the evolution of technologies and the media have played an essential role in how we consume and enjoy the game of football.

Football Archaeology is reader-supported. Click here to buy one of my books or otherwise support the site.