Today's Tidbit... Football Training Camp In The 1910s

It is that time of year. College football training camps are opening nationwide, almost all filled with hope, if not optimism, since we are one month from launching a new season. Most camps are held on campus nowadays, though some venture off for bonding and other purposes.

Still, the modern training camp differs from that of the 1910s. Today, athletes remain on campus and condition year-round. Even the freshmen arrive months before fall classes start to get into the flow. Players work with ten on-field coaches, all of whom are full-time employees, as well as strength and conditioning coaches, analysts, and trainers, and teams start camp with their offenses fully installed or nearly so. Training camp hones football skills rather than preparing teams to do so.

"Training camp" was first tied to college football in the late 1890s. At the time, the season began in the third or fourth week of September when classes were in session, and teams often did not start serious football training until a week or two before their first game, which is much of the reason big-time teams scheduled lesser foes early in the season. Before regular practice began, however, many teams held training camps that received their name because they occurred at remote locations where the teams often camped in tents. Resorts with permanent cabins hosted some camps, but many were found on land owned by an alum with open spaces, hiking trails, and a swimming hole.

Part of what is striking about newspaper accounts of training camps in the 1910 era is the lack of preparedness on multiple levels. For example, in 1908, Mount Union's athletic director was still deciding whether to take the team off campus one week before the start of camp. In 1910, Texas A&M head coach Charlie Moran ran training camp as a one-man show. His only assistant, the former Yale player L. H. Andrew, did arrive in College Station until camp ended. The 1914 Oregon team could only hold their training camp after a late effort by local merchants provided $800 in funding. Who could have imagined local business owners donating big money to the Webfoot program?

And then there were the players. Depending on the school, some players spent the summer working on farms or performing other physical work, but most did not otherwise physically prepare for football. They did not lift weights or engage in any form of directed conditioning, so the entire point of training camp was to acclimate their bodies to the rigors of football practice that began once they returned to campus.

The typical camp activities consisted of a morning hike or run and two or three hours in the afternoon of signal drills, passing and falling on the ball, calisthenics, and punt and kickoff coverage. Like most, Texas did not take football gear to their camp in 1913, other than a few footballs. The yearbook summary below mentions that Texas' 1913 training camp was also an opportunity to haze the freshmen, a practice that could shift from goodhearted fun to abhorrent, as events at Northwestern show.

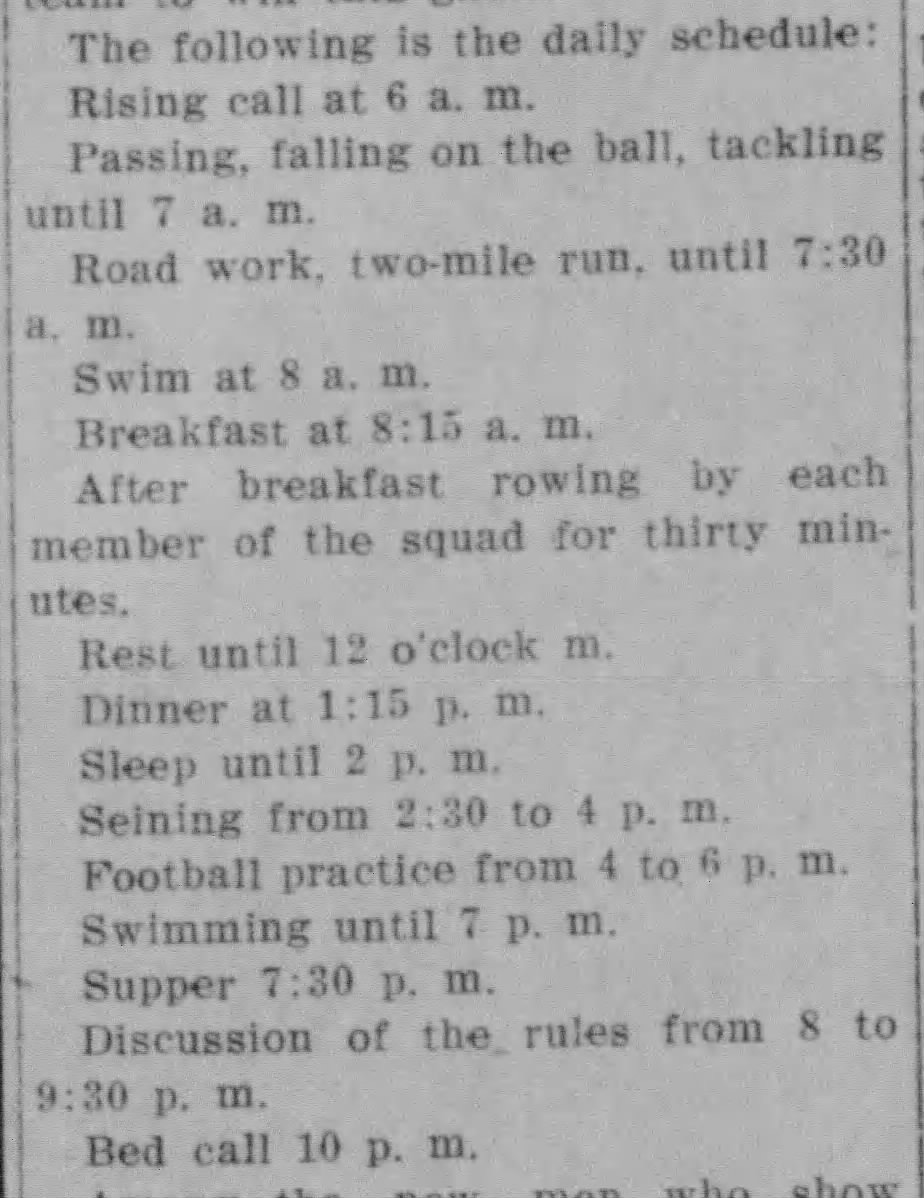

Further west in Texas, A&M employed a camp schedule that included an hour-and-one-half of seining, which, best as I can tell, involves catching fish with a long net. Seining may have been their term for a scheduled swim, but it points to the relaxed nature of the camps.

Camp schedules included classroom time to cover offensive and defensive plays and new rules. Overall, however, the pace at camp was far more relaxed and geared toward team building rather than football play. The real work began only after returning to campus.

Football Archaeology is reader-supported. Click here to buy one of my books or otherwise support the site.

I love your articles and look forward to them daily. Thanks!