Today's Tidbit... Getting A Kick Out Of The 1914 Rules

Although the 1914 football rules included fourteen rule changes, most were of a modest, technical nature that did not significantly alter the game. However, that does not mean the rule changes were uninteresting. Two of the changes affected the kicking game, making it more rational while also prompting one to ask why they created the old rules.

The first rule change related to kicked balls hitting the goal posts, and stemmed from an incident in the 1913 Harvard-Yale game, best remembered for Harvard's Charles Brickley kicking five field goals in a 15-5 Crimson win. Yale scored one field goal and benefitted from a Harvard safety, which led to the rule change.

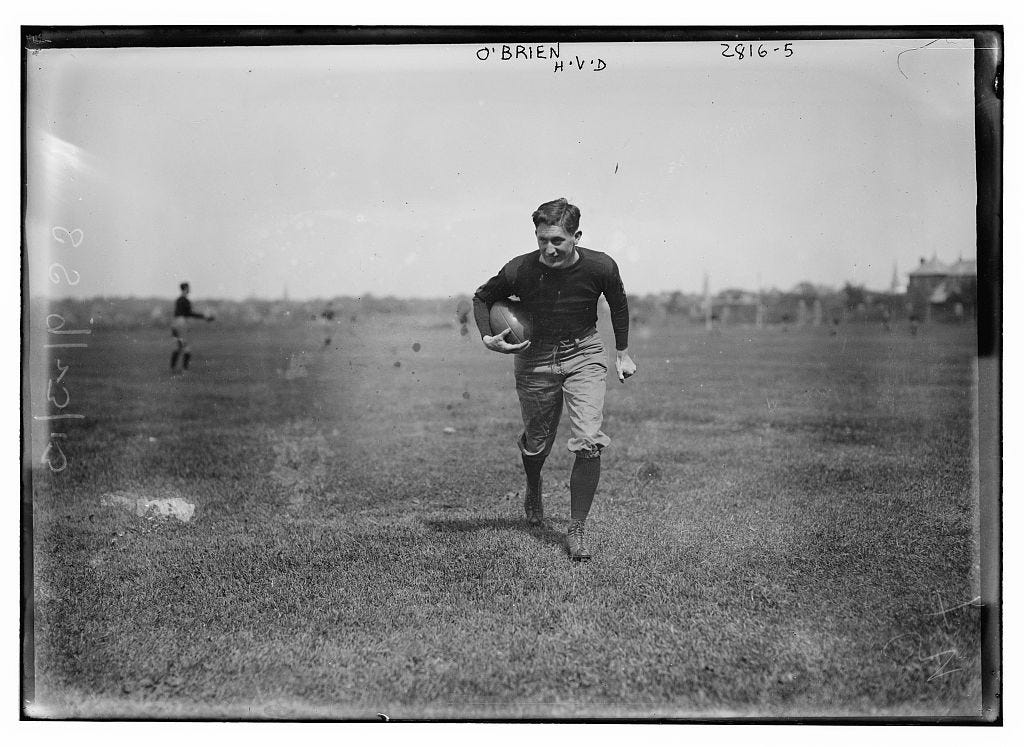

Following the first of Brickley's field goals, Yale kicked off to Harvard, as the team scored upon was responsible for kicking off in those days. Yale booted the ball well enough that it struck the goal posts and bounded back onto the field. Frank O'Brien of Harvard, in a moment of confusion, picked up the ball, stepped behind the goal line, and downed it, thinking the play resulted in a touchback. It did not, and W. S. Langford, the referee, awarded Yale two points.

O'Brien's confusion stemmed from the convoluted rules of the time. Field goal and extra point kicks that hit the goal posts and did not bounce over the crossbar were dead balls. Likewise, punts and forward passes hitting the goal posts became dead balls. Kickoffs, which seldom traveled far enough to strike the goal posts, remained live upon hitting the goal posts.

Of course, since the rules were sufficiently confusing to cause an error by a Harvard player, the rule makers of 1914 chose the consistency route and made kickoffs striking the goal posts dead as well.

The second kicking-related rule change is more bizarre. In the mid-1890s, many fouls resulted in a loss of possession rather than a distance penalty, but things were beginning to shift toward distance penalties.

Teams focused more on field position than possession at the time, and having the team scored upon perform the kickoff meant the scoring team often found themselves deep in their territory.

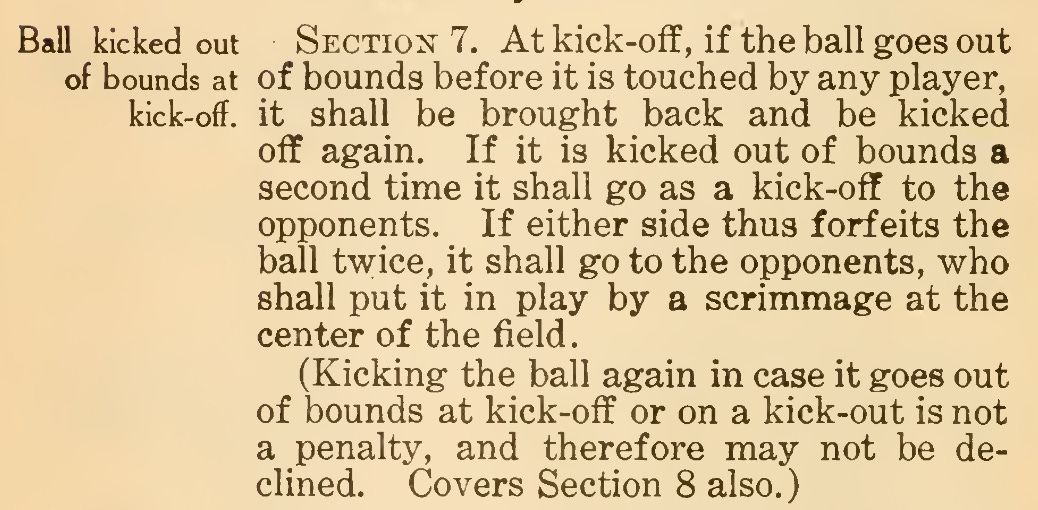

Similar logic led to a kickoff rule, whereby if Team A's kickoff went out of bounds without being touched by a Team B player, Team A would return to midfield to kickoff a second time. If the second kick also went out of bounds, Team B then kicked off at midfield. If their kick went out of bounds, they also kicked off a second time from midfield.

If Team B's second kickoff also went out of bounds, then Team A received the ball and put it in play at midfield.

The 1914 rule change streamlined much of that nonsense. Now, if Team A's kickoff went out of bounds, they returned to their 40-yard line and kicked again. If Team A's kick went out of bounds a second time, Team B put the ball in play at their 40-yard line.

Oddly, at the time of the rule change, no one on the committee recalled ever hearing of an instance of four straight kickoffs going out of bounds, yet the rule had been on the books for 20 years. Ultimately, they simplified the rules while also giving Team B possession and a favorable field position.

Football Archaeology is reader-supported. Click here to buy one of my books or otherwise support the site.