Today's Tidbit... Getting Your Signals Crossed

Teams getting their signals crossed has been in the news lately—maybe you heard about it. A different group of high schoolers, seen below, got their signals crossed around 1910. They played when only a few teams had ever worn numbers on their jerseys, yet some of the guys have addition or multiplication signs on their chests.

The quarterback, fullback, and left halfback have plusses on the front. A close look shows the left end, tackle, and guard have plusses front and back, while the rest of the team is blank, other than the tall guy in the back wearing the multiplication sign. Maybe there was some logic for who wore what on their chests, but I'm guessing someone screwed up.

Beyond uniform mixups, most references to crossed signals of the era relate to misunderstanding the signals or play calls. Teams did not huddle before the early 1920s. When one play ended, they quickly lined up for the next play, at which point the quarterback called out the signals. Like today's audibles, the opponent could hear the signals so teams encoded the play call in a series of five or eight numbers. A number in the 20s might mean the next number indicated the play to run. The following number might tell the team whether to snap the ball two, three, or four numbers later. Since college teams might have 50 or 60 plays named only by number, each player had a lot to memorize.

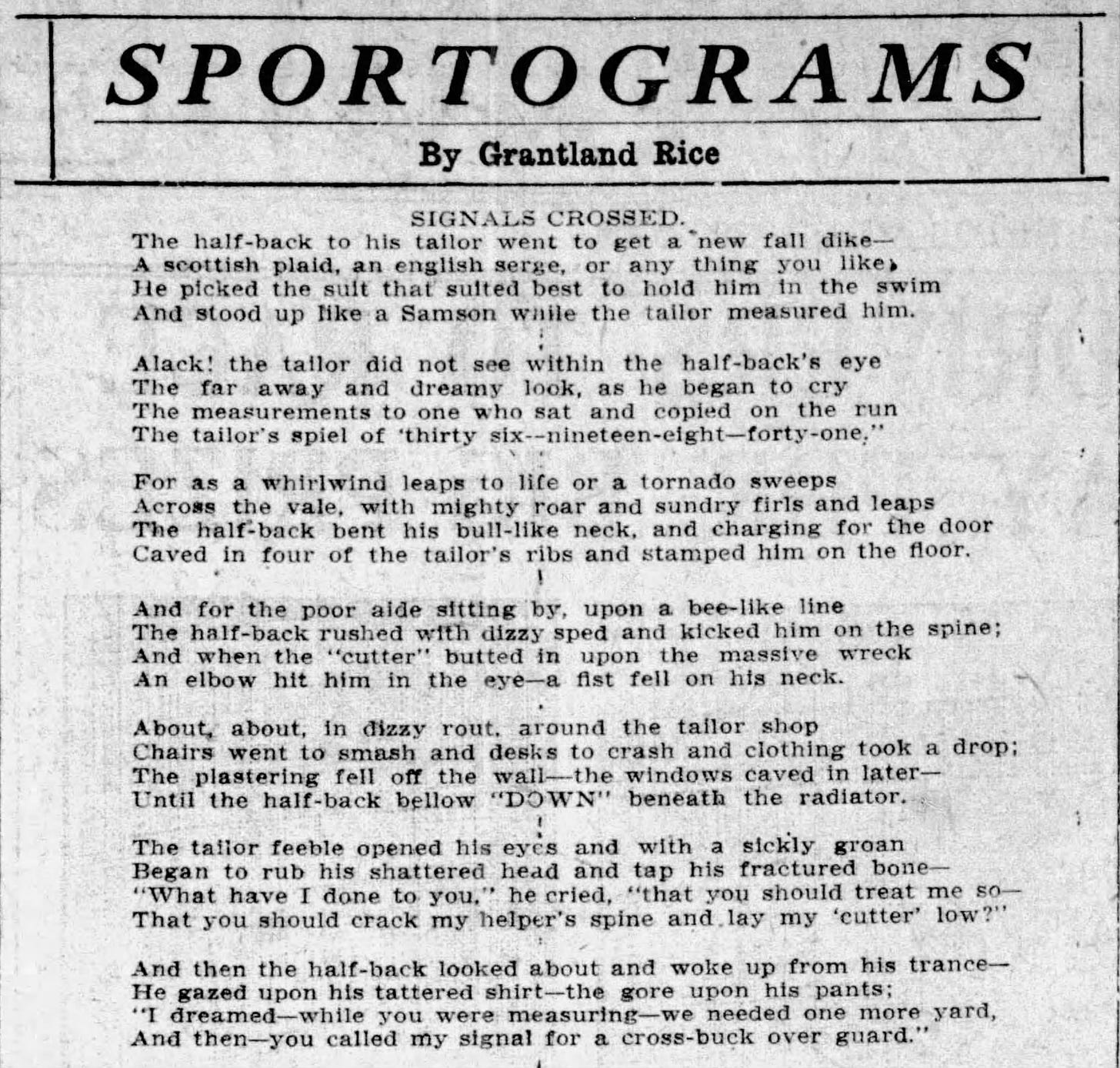

Mistakes were common, leading Grantland Rice, who played football and baseball at Vanderbilt, to write a poem, Signals Crossed, in 1909.

While not Rice's finest work, it provides an amusing example of what happens when signals get crossed. In this case, a halfback a tailor was measuring for a suit hears a series of numbers called out and reacted inappropriately to the situation.

Grantland Rice invented the story described in the poem since no one in real life would use signals or Signals in situations they shouldn't, right? Yeah, it could never happen.

Click Support Football Archaeology for options to support this site beyond a free subscription.