Today's Tidbit... Harvard's Jarvis Field

One of the beauties of college football is that campus stadiums largely stay in place. They are remodeled, modernized, razed, rebuilt, or have other terrible things happen to them, but they largely remain in the same spot. Pro stadiums move from the central city to the suburbs and back again. Pro franchises even relocate to new cities, sometimes moving across the country, while college stadiums remain right where they began.

The location of Harvard's on-campus football fields has shown some instability but considering that Harvard Stadium has been in the same spot since 1903, we can forgive a few early moves. Harvard's Jarvis Field hosted the first rugby match played in America in 1874, making it the grandfather, great-grandfather, or some level of greatness to all football fields since then.

Harvard Stadium and Jarvis Field are neighbors. The stadium sits on one side of the Charles River, while Jarvis Field sat on the other. The location of historic Jarvis Field is now the site of the Kennedy Graduate School of Public Administration.

Lucius Littauer donated the money for Harvard's Graduate School of Public Administration, later renamed for JFK. Today, one of the Kennedy School's buildings is named for Littauer. Fittingly, the five-term member of Congress played football for Harvard in 1878 and was the team's first coach in 1881, so he played and coached on the ground where an academic building now stands that is named in his honor.

As mentioned, Jarvis Field hosted the first rugby match in America in 1874, so the goal posts built for the game were the first to rise in America. By charging 50 cents admission to offset the cost of the banquets they threw for McGill, Jarvis was the site of the first admission fees to a proto-football game. (Morton Prince '75, then the Harvard Foot Ball Club secretary, claimed they collected enough money that the champagne flowed freely those evenings.) Tufts and Harvard played on Jarvis Field in 1875, making it the site of the first rugby match between American colleges.

Over time, Jarvis Field got a bit fancier. They built wooden bleachers that held several thousand fans and expanded those to extend the field's length.

Other notable events that occurred on Jarvis Field included:

The first Harvard-Princeton game, which occurred in 1877.

The second kickoff return for a touchdown ever came when Joseph Sears ran one back versus Penn in 1886 (per Parke Davis). (Note: Kicking teams in early football often dribble-kicked the ball, picked it up, and ran with it. Since they did not always kick to their opponents, there were limited opportunities to run one back.)

The first spring practice was held on Jarvis Field in 1889 under captain Arthur Cumnock's guidance.

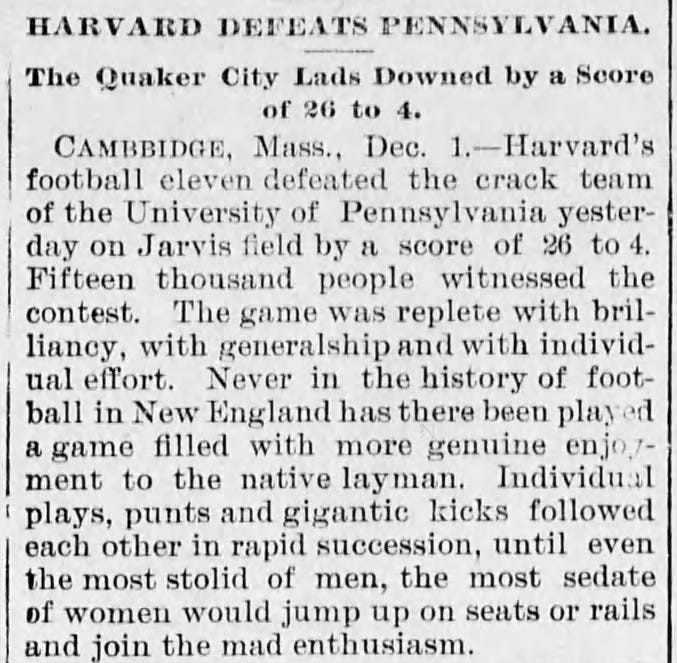

Things began changing in 1890 when an alum, Henry L. Higginson, donated 20 acres of swampy land across the Charles River for athletic fields to honor Harvard's Civil War dead. Soon after, alums acquired and donated other lots, and then funded dikes, drainage systems, and the fill to make the land suitable for athletic purposes. The last varsity football game at Jarvis Field came at the end of the 1893 season when Harvard beat Penn 26-4 with 15,000 fans in attendance.

They laid out a new gridiron across the river, played there in 1894 and 1895, and then relocated it on Soldiers Field before building Harvard Stadium.

After the football games crossed the river, tennis courts appeared on Jarvis Field in 1896, growing in number until they had 90 by 1925. Some courts disappeared in 1946 when they built family housing for returning veterans, and those gave way to the Kennedy School buildings.

So, Jarvis Field is no more, but the Crimson developed aspects of football while playing there that echo today. If old football fields like Jarvis Field could talk, what would you ask them?

Postscript:

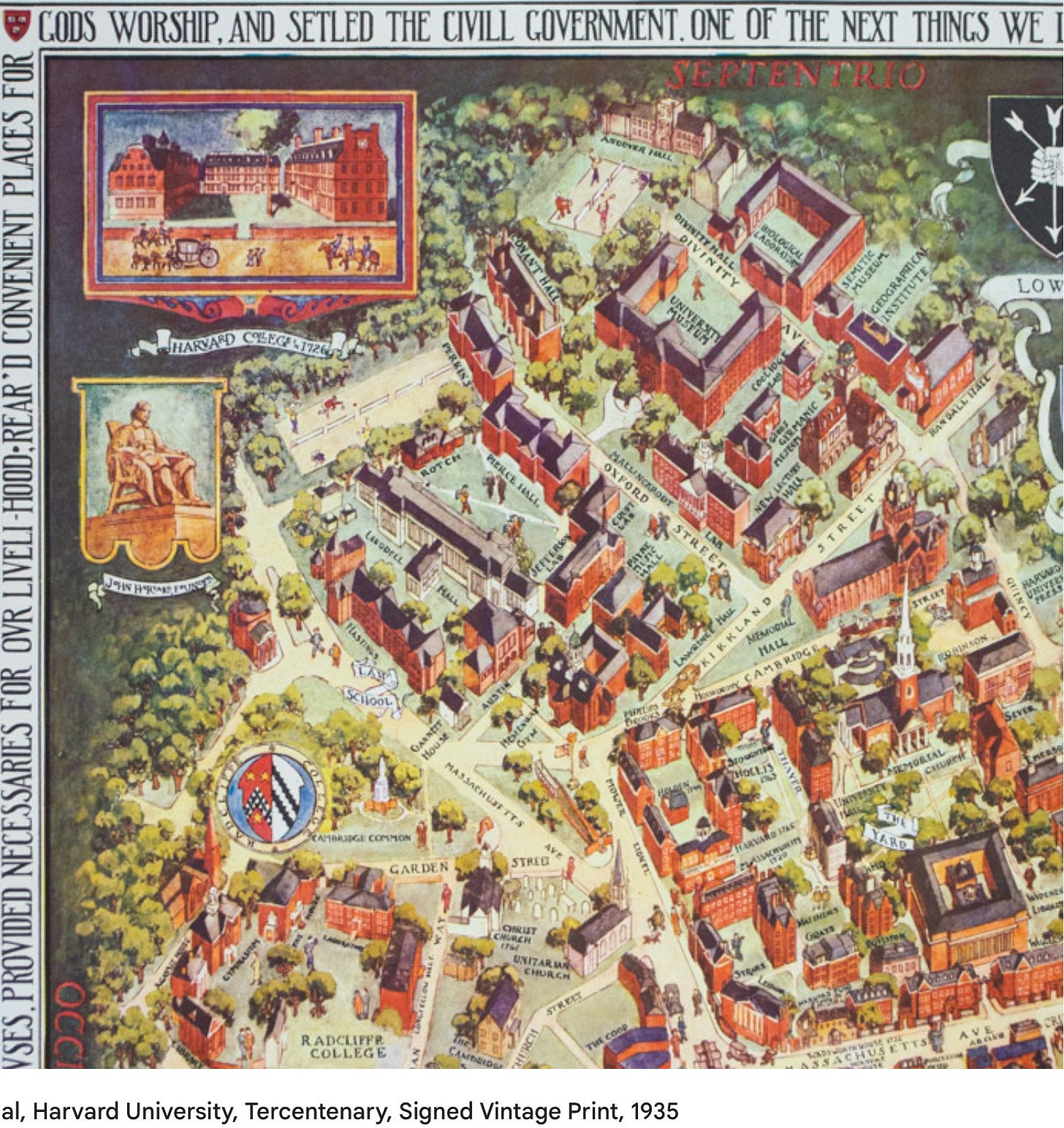

So, I relied on some bad sources, per the comments below. Jarvis Field was not where the Kennedy Schools not sits. It was part of the central campus. The 1935 map below shows tennis courts in the upper left and is the former location of Jarvis Field.

Click Support Football Archaeology for options to support this site beyond a free subscription.

Percy Haughton may or may not have invented the mousetrap, but he surely helped refine and popularize it. Here's what Percy said about the mousetrap, as quoted in (shameless plug alert!) my book "The Coach Who Strangled the Bulldog: How Harvard's Percy Haughton Beat Yale and Reinvented Football":

"Grantland Rice recalled that before one Yale game, he mentioned that the Elis had a big, hard-charging line. 'I only wish they were twice as fast,' Haughton responded. 'We'll let them through and then cut them down.'"

I’d ask what it was like seeing Percy Haughton engineer the very first trap play, appropriately called the “mouse trap.”