Today's Tidbit... Harvard's Kicking or Graduates' Cup

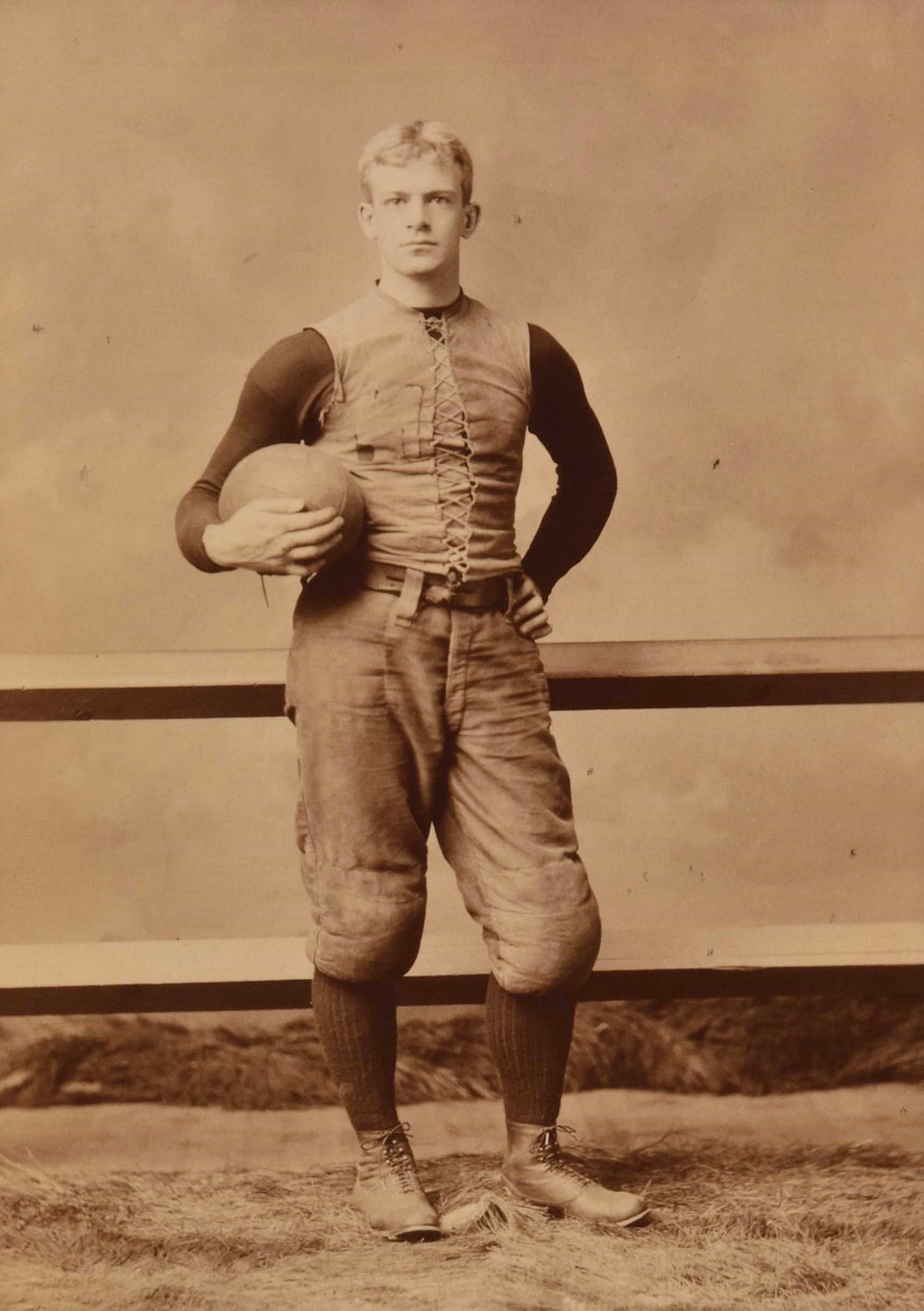

Arthur Cumnock was Harvard's football captain in 1890 and is best remembered as the inventor of the nose guard, a forerunner of the face mask. As captain, Cumnock was the first to train his team during the spring (giving us spring practice) and to practice tackling indoors using what became known as a tackling dummy. (Amos Alonzo Stagg developed a similar device that year while captaining Yale.)

As someone consumed with improving his team, Cumnock sought a way to improve the state of drop and placement kicking at Harvard and worked with several Harvard alums to create the Graduates' Cup. The alums donated $250 for a silver cup with gold lining. Unfortunately, I could not locate an image of the cup, but it was ten inches tall and ten inches across at the mouth and was to be awarded each year to Harvard's best kicker, as determined by contest. The plan was for each year's winner to have their name engraved on the cup and, after ten years, the player scoring the most points in a given year was to take possession of the cup.

Cumnock and the alums created a detailed set of rules for the contest, which the team captain oversaw. The competition involved attempting three drop kicks from the 25-, 35-, and 45-yard lines and three placement kicks from the 30-, 40-, and 50-yard lines. Kicks made from the 25- and 30-yard lines earned two points. Those booted from the 35- and 30-yard lines earned three points, while more distant kicks brought four points.

Up to 25 players participated each year, so the 450 kicks sometimes took a few days to complete. J. A. Dennison was the surprise winner of the 1889 contest, sealing the victory by making three successive kicks from the 35-yard line.

Bernie Trafford, who captained the team in 1891 and 1892 and made five field goals against Cornell in 1890, won the next two years. The 21 points earned in 1890 was the highest point total in the early years, putting him in a position to take home the cup after a decade of contests.

Under Trafford's supervision, they held the contest in 1892. Unfortunately, a newspaper article provides details of the first day's events but not the second, so that year's winner is unknown.

Information about the Graduates' Cup is missing for the next quarter century as the next contest report came in 1916. It may be that someone found the cup in a storage closet and decided to restart it, but they held the competition once again, with Ralph Horween declared the winner.

Horween went on earn to All-America status in 1919. He and his brother Arnie, who captained the 1920 team, played in Harvard's only bowl game, a 7-6 win over Oregon in the 1920 Rose Bowl.

Unfortunately, the Graduates' Cup trail goes cold again after 1916. Perhaps America's entry into WWI led Harvard to forego the contest in 1917, but it will remain a mystery until someone again picks up the scent of Harvard's kicking cup.

Football Archaeology is reader-supported. Click here to buy one of my books or otherwise support the site.