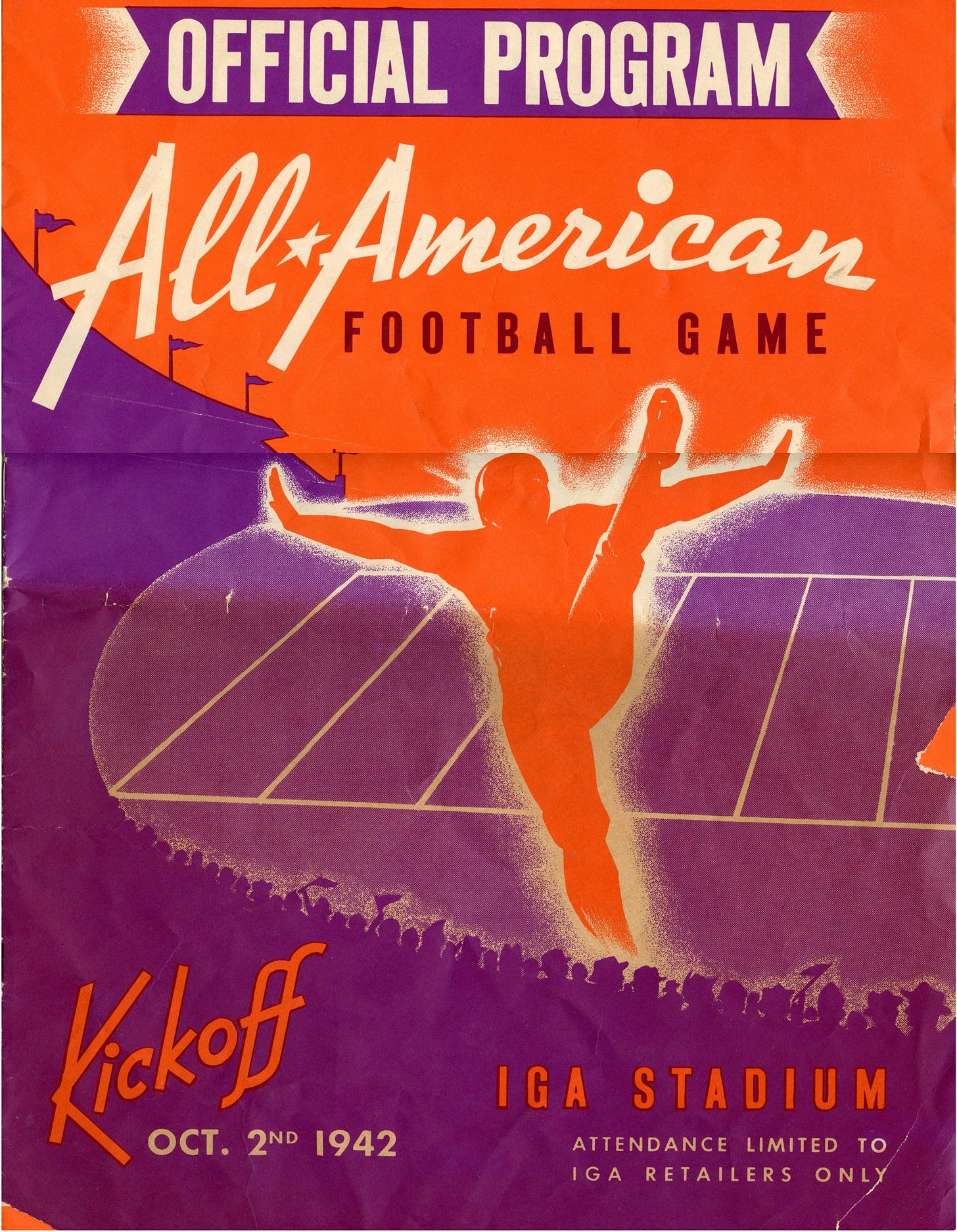

Today's Tidbit... IGA's Football-Themed Incentive Program of 1942

Football sells. It grabs headlines and attracts attention, so many businesses align themselves with specific players, teams, and leagues. Others avoid paying licensing, royalty, or endorsement fees by associating themselves with the sport in general, such as when the Independent Grocers Alliance or IGA developed a football-themed incentive program in 1942, hoping to promote the sale of various grocery products.

Since I worked for several decades for a marketing services firm that pioneered the sales incentive business, the IGA brochure seemed like a fun item to review in these dog days of summer. Plus, the brochure has fabulous period artwork that is worth sharing.

Wiki tells us that IGA had 3,000 independently owned retail locations in the U.S. in 1930 versus less than 800 today. Today, most IGA stores are in smaller towns that do not attract the attention of the regional and national behemoths. Still, IGA was among the nation's leading retailers in 1942, so any promotional contest they ran had a widespread impact.

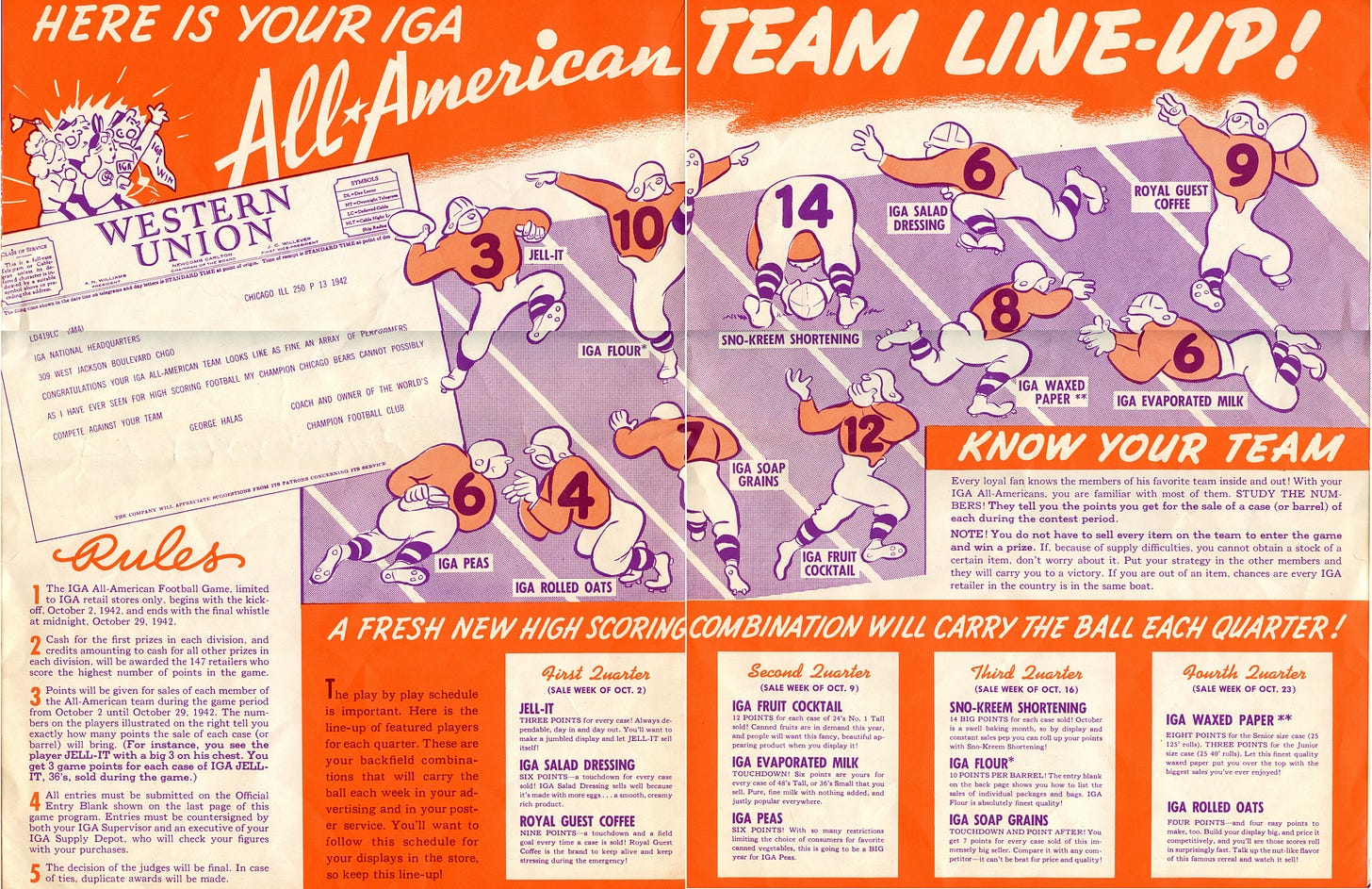

The primary purpose of a sales incentive program is to sell more stuff, and they work by incentivizing retailers to sell specific stuff, specific amounts of certain stuff, or the most stuff. Since some IGA retailers were larger than others, the contest had tiers. The little guys competed with the little guys and the big with the big, resulting in three competitive tiers based on the retailers’ annual purchase volume: Scholastics, Collegians, and Professionals.

We've all seen advertisements featuring Joe Montana or someone wearing team-colored gear that is sufficiently generic that the advertiser can avoid paying licensing fees. Although licensing was uncommon in 1942, the IGA brochure included a telegram from George Halas, the Chicago Bears owner and coach whose team won the 1941 NFL championship and lost in the 1942 title game. Halas was known to throw nickels around like manhole covers, so you can bet he was paid for the use of his name.

The contest kicked off in October, targeting different products each week (aka quarters). Retailers earned points by selling cases or barrels of those products during the contest. Those who earned the most points earned the biggest prizes.

How did the retailer increase sales of IGA flour or Sno-Kreem shortening during the correct week? Advertising. Even better, collective advertising, like the eleven retailers who banded together to pitch their All-American products in the October 15 issue of the La Crosse Tribune. Similar ads appeared across the country.

Price discounts, in-store posters, and the Brand Stand display enticed consumers to buy extra peas or flour that week.

Retailers were also encouraged to promote the contest in the store and use door-to-door selling, awarding local youths with War Stamps for racking up the sales. At least one retailer gave away footballs to the local kids earning the most points during the contest.

And there was paperwork. Retailers had to log the amount of product on hand at the start of the contest, the amount ordered during the contest period, and the amount on hand at the close of the contest to determine who might win the cash and warehouse credit prizes.

Now, some might think this story has nothing to do with football. In fact, it has everything to do with football, at least at the professional and major college level, where the sport is a business that succeeds by bringing in money. We may not like money's impact on the game we love, but it's nothing new. Just ask the IGA retailers and customers of 1942 or George Halas, who made a little NIL money back in the day.

Not that there is anything wrong with that. I do the same thing with paid subscriptions and the links below.

Football Archaeology is reader-supported. Click here to buy one of my books or otherwise support the site.

LOL< I love the picture painted in, "Halas was known to throw nickels around like manhole covers"