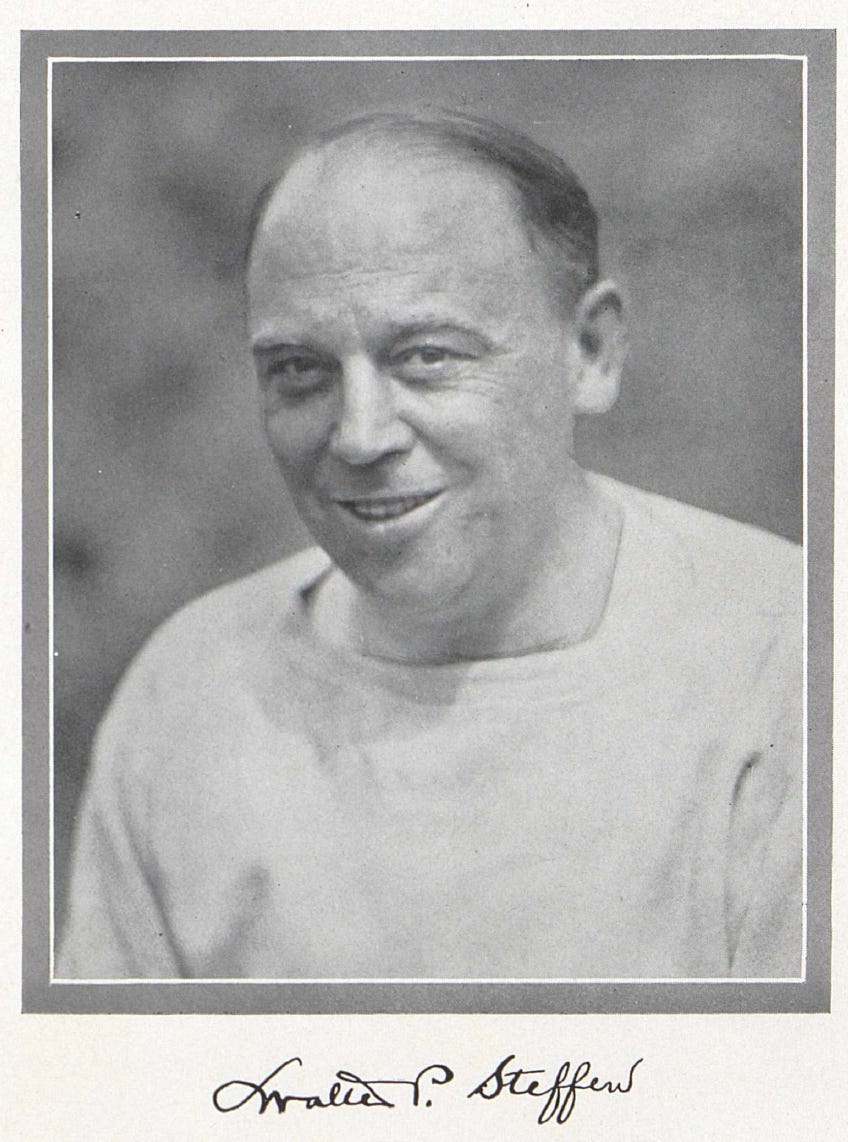

Today's Tidbit... Judging Walter Steffen's Coaching Career

Walter "Wally" Steffen is among the underappreciated football figures who helped shape today's game and did so in ways impossible to replicate today.

Steffen played at North Division High in Chicago before joining Amos Alonzo Stagg's Chicago Maroons. He was a halfback in 1906 when his fellow backfielder, Walter Eckersall, earned All-American honors at quarterback. Steffen replaced Eckersall for the next two years and became the fourth Western player named to Walter Camp's All-American first team.

He spent the next several years assisting Stagg while attending UChicago's law school, and after passing the bar, he worked as an Assistant U.S. Attorney and a Chicago alderman. This job allowed him enough freedom to become Carnegie Tech's head coach in 1914. From 1914 through 1921, Steffen lived in Pittsburgh from September through Thanksgiving to coach football, returning to Chicago on occasion. However, Steffen was elected a judge for the Superior Court of Cook County in 1922, a role that did not allow him to spend three months in Pittsburgh each fall. Instead, Robert Waddell trained the team during the week while Steffen was in Chicago. Steffen then traveled to Pittsburgh or the away game location each weekend for games.

One way or the other, being the "Commuter Coach" worked despite upgrading the Tartans' strength of schedule during the 1920s. His 1926 team, for example, beat three lesser opponents plus Pitt, Detroit, and West Virginia and gave Notre Dame their only loss of the season when Knute Rockne famously skipped traveling to Pittsburgh so he could watch the Army-Navy game in Chicago.

To show the 1926 win was not a fluke, an undefeated Carnegie Tech went to two-loss South Bend late in the 1928 season and gave the Irish their third loss and Rockne's first loss in South Bend since taking over in 1918.

Part of Carnegie's strength came from Steffen's primary offensive innovation, the spinner, in which the player receiving the snap turned 180 degrees, his back to the defense when he faked or gave the ball to one back or another running left or right. John Heisman claimed to have invented the spinner in 1910, but he did not make it central to his offense, and it goes unmentioned in his 1922 Principles of Football.

Steffen began using the spinner in 1924 with his star fullback, Dwight Beede, who would invent football's penalty flag in 1941. The spinner quickly became a standard component of offenses nationwide until the Modern T arrived in the 1940s.

As the 1930s dawned, Steffen remained the formal head coach, but he increasingly served in an advisory capacity while Waddell was the field coach, and he announced plans to retire after the 1932 season. Being a Chicago alum and a Chicago judge, he and Fritz Crisler were among those thought likely to replace Amos Alonzo Stagg when his term at Chicago ended after the 1932 season. Steffen was not interested in the Chicago job, and he turned down Texas in 1933, as he increasingly suffered from poor health before passing away in 1937.

Steffen had more success than most of his peers despite being a part-time coach, managing an 88-53-9 record in 18 years on the Carnegie Tech sideline. Nevertheless, he is best known for having given Rockne two of Rockne's twelve losses in his 13 years coaching the Irish. (Fred Dawson of Nebraska matched that feat, while Howard Jones beat Rockne once at Iowa and twice at USC.)

Today, Steffen is largely forgotten. Carnegie Tech's, now Carnegie Mellon's, shift to DIII football has not helped his legacy. Still, as a former All-American and a notable coach for nearly two decades, he deserves his spot in the College Football Hall of Fame.

Football Archaeology is reader-supported. Click here to buy one of my books or otherwise support the site.

Great write up on this important figure in gridiron history. That first image is so crisp for being almost 100 years old that it looks 3D.