Today's Tidbit... Minnesota's Spinner and Their Ineffective Passing Game

We're taking a spin today, back to the days of the Single Wing and half-and-full spinners. The spinner arrived in football in 1924 when Walter Steffen, Carnegie Tech's coach, employed it with his quarterback Dwight Beede, who 20+ years later invented the penalty flag.

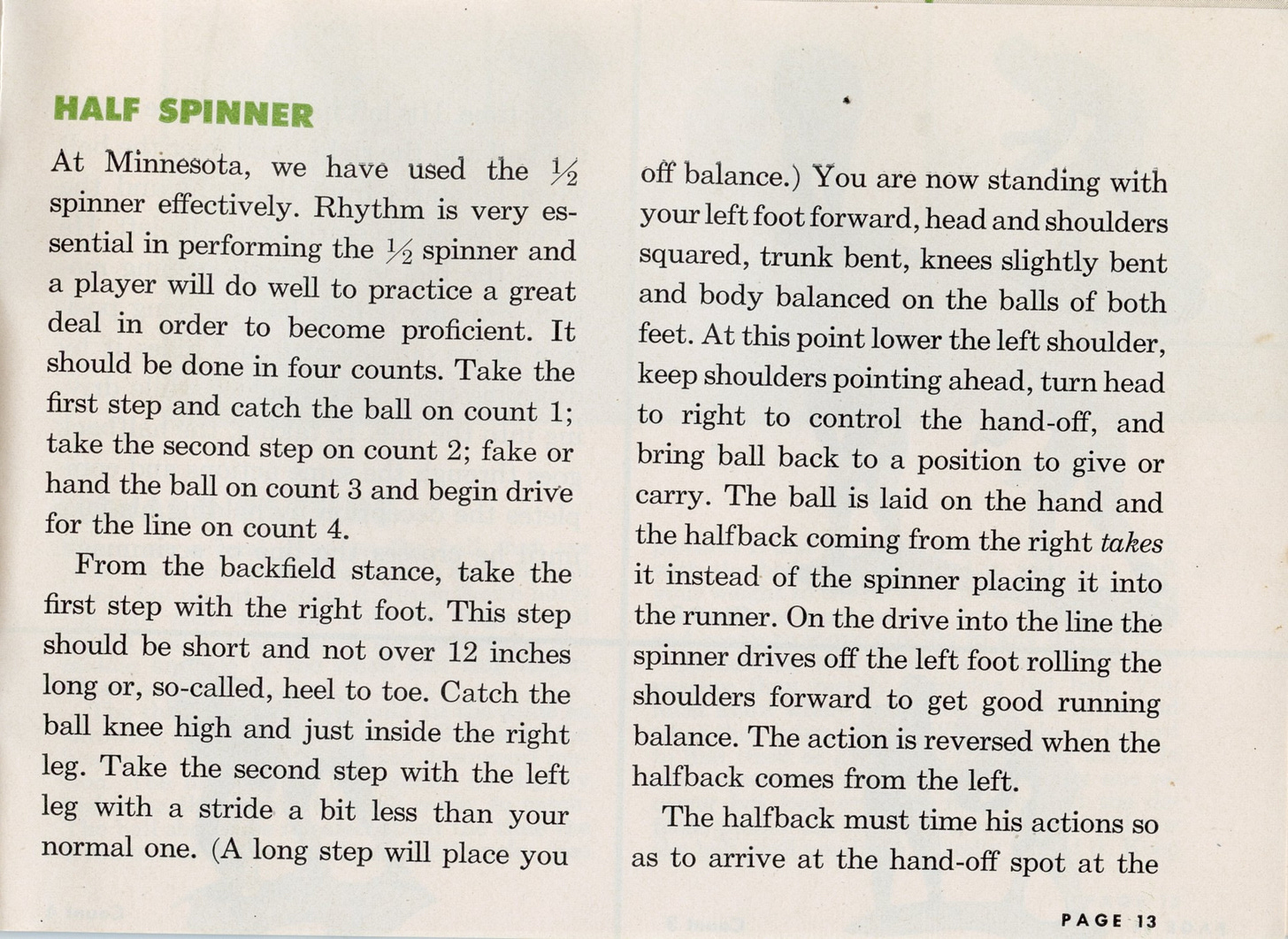

The spinner was a component of the backfield faking and misdirection in series plays in which each play looked like another. Minnesota coach Bernie Bierman shared his preferred half-spinner techniques in his Want To Be A Football Champion? pamphlet published as part of the Wheaties Sports Library.

While the half-spinner described in the pamphlet had the back receiving the snap and handing the ball to a teammate, on other plays, the back receiving the snap fakes the handoff, keeps the ball, and dives into the line of scrimmage or sweeps.

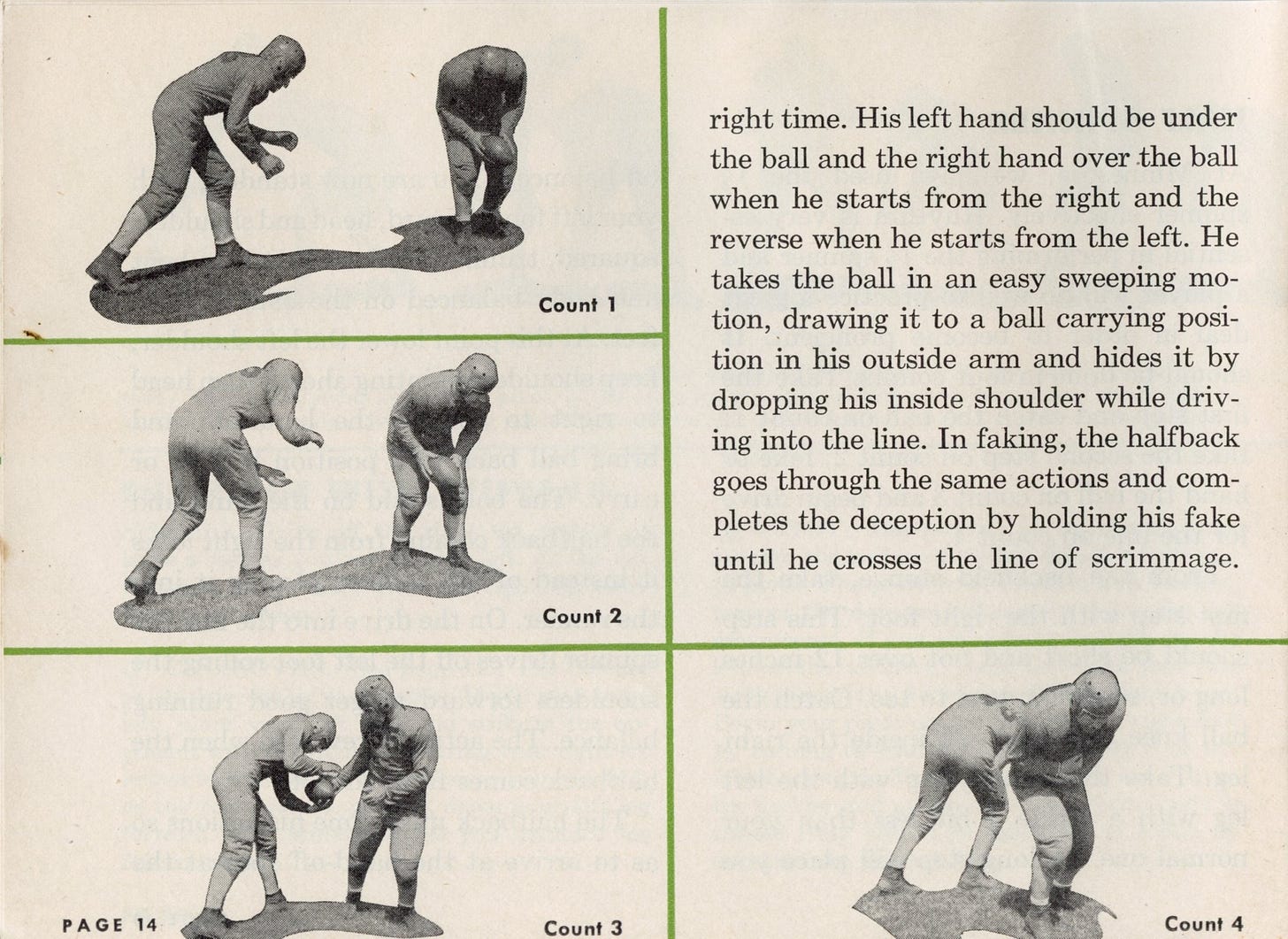

Bierman's pamphlet also shares six of Minnesota's Single Wing plays run from an unbalanced formation with the ends split four yards. The first three comprise a series in which the ball is snapped to the fullback.

On the first play, the fullback keeps the ball and dives off tackle following the guard's trap block. A version of this play is seen in the link below (@ 0:55), though the quarterback in the video starts under center before reversing out and sweeping opposite the fullback dive.

The second play shows similar action, but the fullback gives the ball to the spinning quarterback, who then reverses out and pitches to the sweeping tailback. The third play shows similar action as the second, but the sweeping tailback has the option to pass the ball, ideally to the backside end.

The first spinner play I found in the video had Michigan’s fullback executing the spinner, faking the handoff, and diving into the line with the ball.

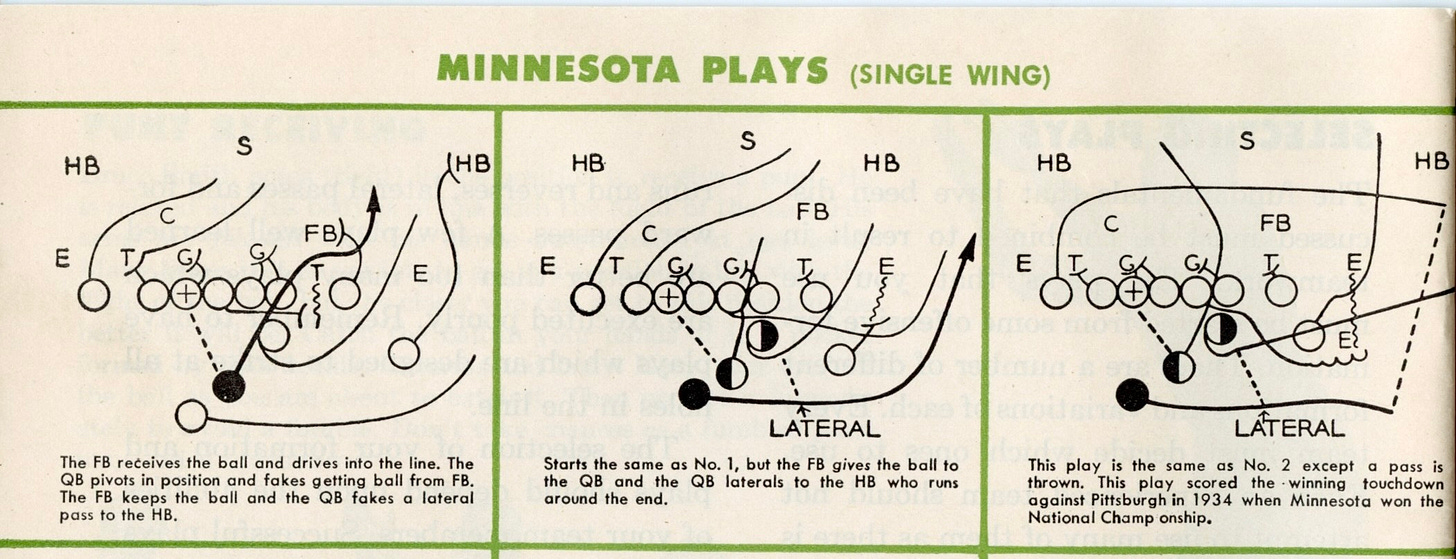

In the second set of the plays, the ball is snapped to the tailback. On the first play, he keeps the ball after faking to the right halfback, who sweeps left; on the second play, he gives the ball to the right halfback. The third play is a pass by the right halfback as he runs to the left.

One thing that is striking is the low quality of Minnesota's passing game (and others of the era). With his blockers unable to use their hands and arms in blocking, the passer is consistently under pressure, seldom has his feet planted, and often throws into coverage. See the two plays starting at 4:08.

A poorly executed screen pass at 6:24 also suggests it was going to be a long day for the Gophers.

Minnesota lost the 1946 Little Brown Jug game to Michigan 21-0. By then, the forward pass was 40 years old, yet it still had a long way to go to become as reliable a means of moving the ball as it is today. The 1946 season was the first year since 1909 that college football did not require the passer to be five yards behind the line of scrimmage when throwing. Cup protection was in its infancy, and it would not be until the late 1970s and 1980s that offensive players could use or extend their arms when blocking.

It's no wonder many coaches of that generation preferred running the ball over passing it.

Football Archaeology is a reader-supported site. Click here for options on how to support this site beyond a free subscription.

Tim, have you done a piece on the changes in the blocking rules? What I remember from late 50s to early 60s was hands on chest and elbows down. How did the rules evolve?

Would also be nice to see an update on the so far unsuccessful campaign to correctly label the "Lockney Lines." Broadcasters still call them hashmarks, which as you have written are something else, still exist, but preceded the Lockney Lines.