Today's Tidbit... Offensive Formations in 1955, Part II

This the second in a series showing elements of Everybody’s Football, a Massachusetts Mutual Life advertising premium from 1955. The book explains various elements of the game as it existed at the time. Previous stories from the volume include:

The first story in the series covered the Single Wing, Notre Dame Box or Shift, Double Wing, T Formation, the Split T and Wing T. Today, we cover the Punt Formation, Short Punt, Triple Wing, and the Spread.

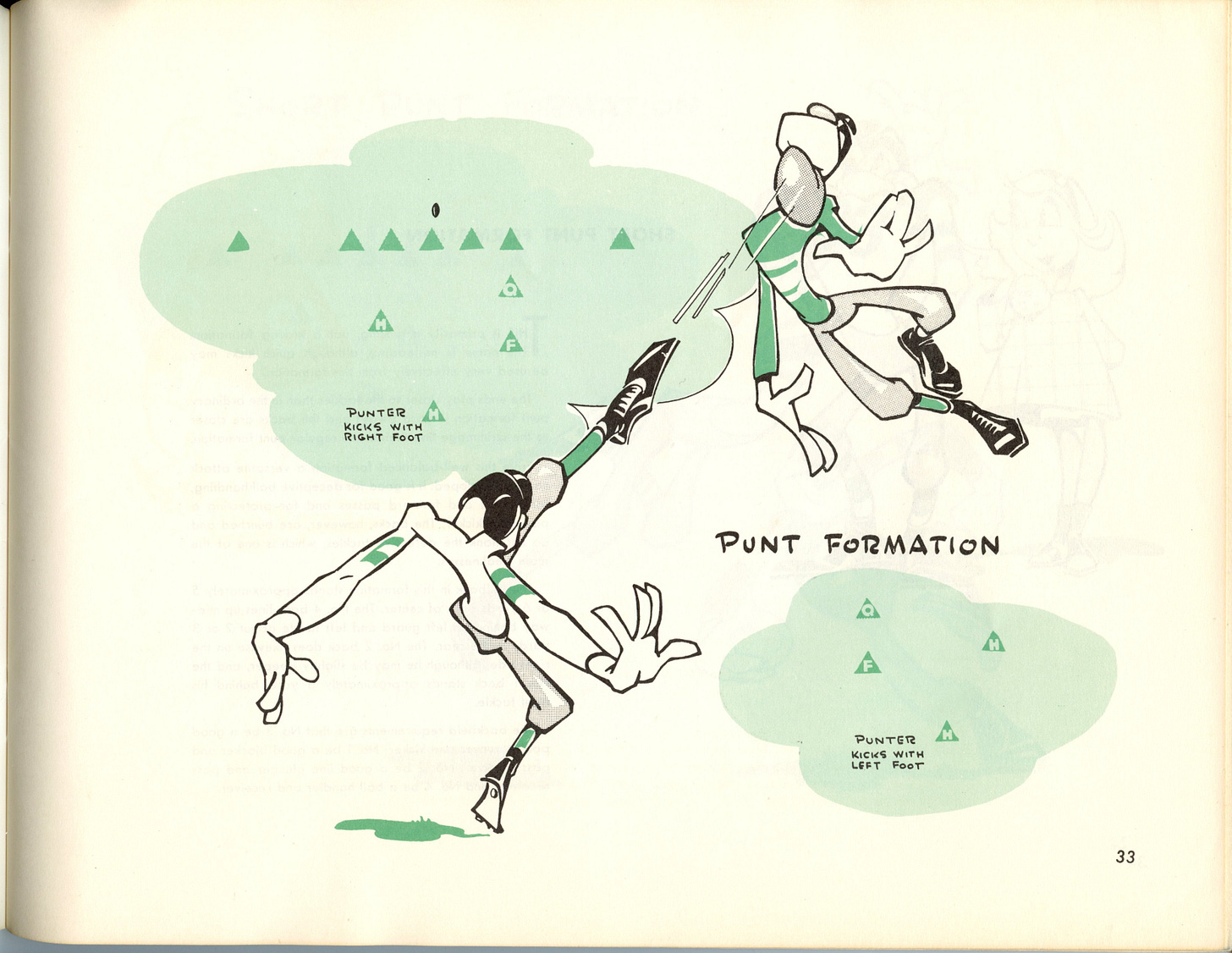

Few of us today view the punt as an offensive formation, but we live in a football world dominated by the forward pass. Today, we view punting as an acknowledgement of offensive failure, but that was not always so. Before unleashing the forward pass in the 1950s, punting was one of the primary methods of moving ball down the field. Teams punted earlier and often, especially if their defense was stronger than their offense.

As noted in the description, the punt formation protects the kicker, while spreading the gunners to give them the opportunity to cover the punt and deny the return.

The description also mentions the return kick, which allowed the team receiving the punt to immediately punt it back to the punting team, a topic covered in a 2023 Tidbit.

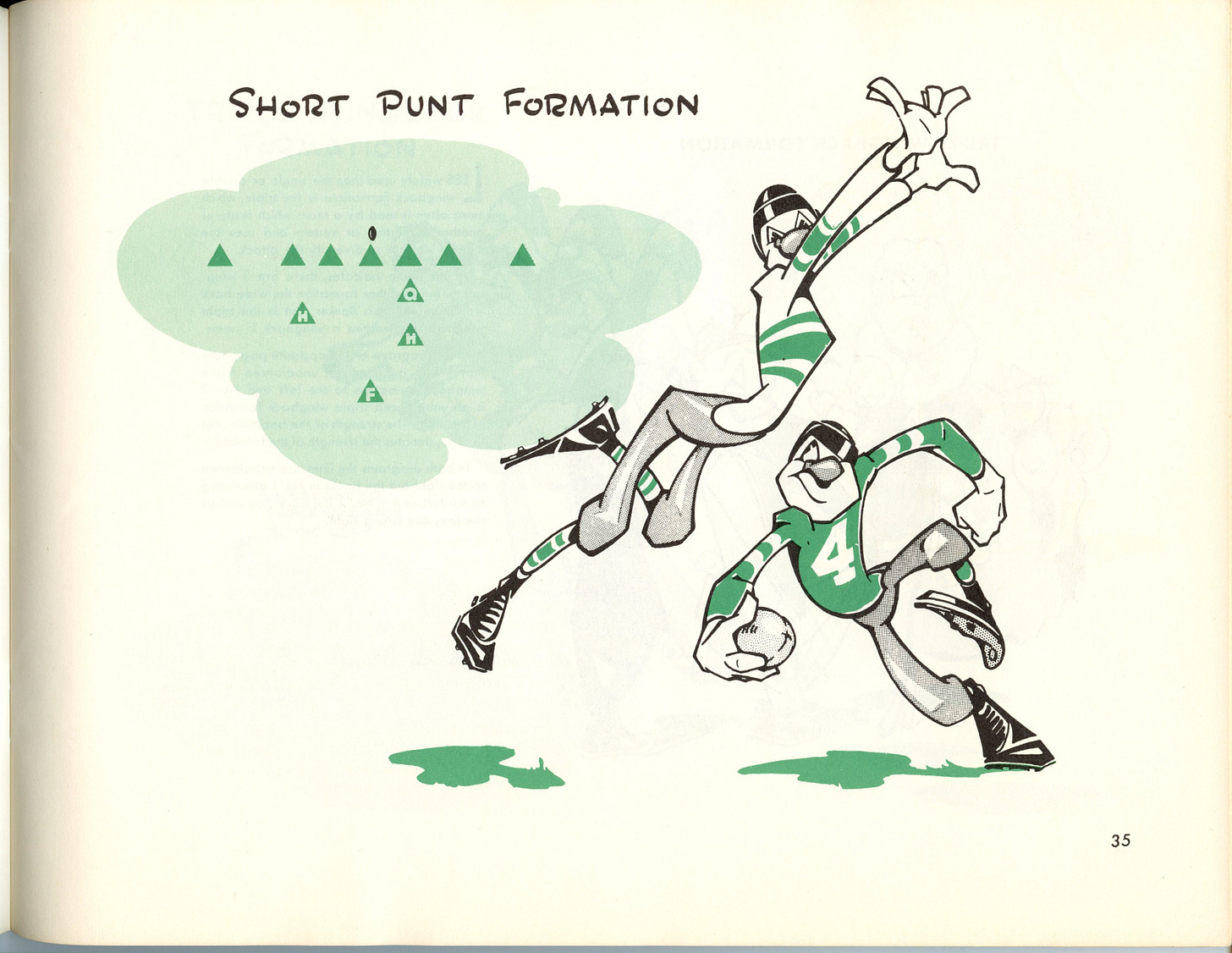

The short punt formation was popular in the early days of forward passing. In fact, it was the primary passing formation for St. Louis U in 1906 when they taught the football world how to throw and catch the ball. Michigan used the short punt extensively under Yost, as did others. A compact version of the punt formation, it allowed teams to run, punt, drop-kick, or pass effectively, so it kept defenses guessing in the days before offenses figured out how to pass block effectively.

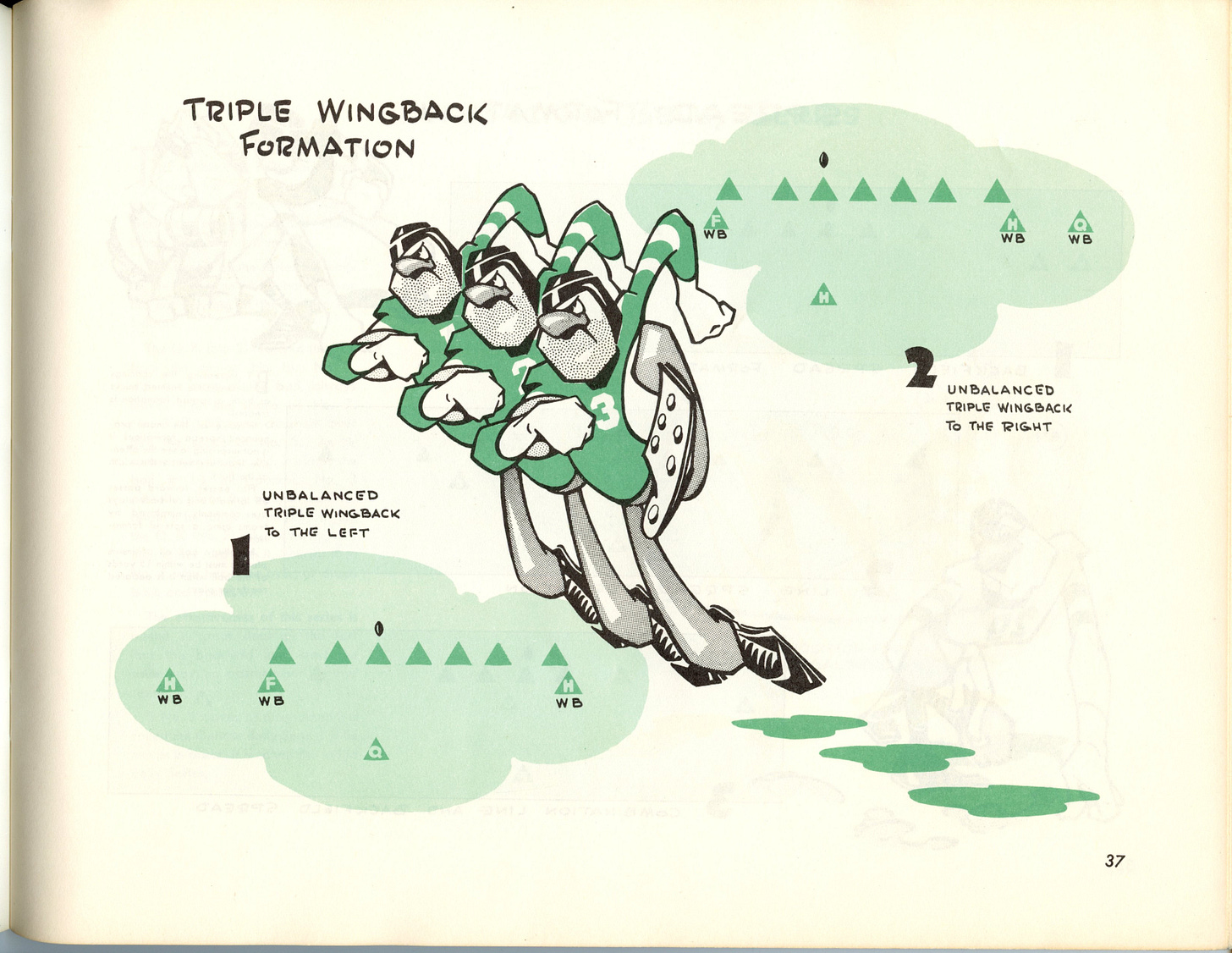

The Triple Wing made the cut in the 1955 volume, though it saw little use at the time. Devised by Tuss McLughrey at Brown in 1932 and picked up Stanford the next year, the Triple Wing was both a power running and pass offense.

Today, we consider the Triple Wing to be an empty backfield formation, though we spread the wings and ends further from the interior linemen. They struggled with spreading out their receivers in the 1930s since the need some for pass protection. They often used misdirection or its threat to keep defenders at bay. Since passers had to be at least five years behind the line of scrimmage then, the direct snap to the quarterback allowed limited quick passing plays, though none like we enjoy today.

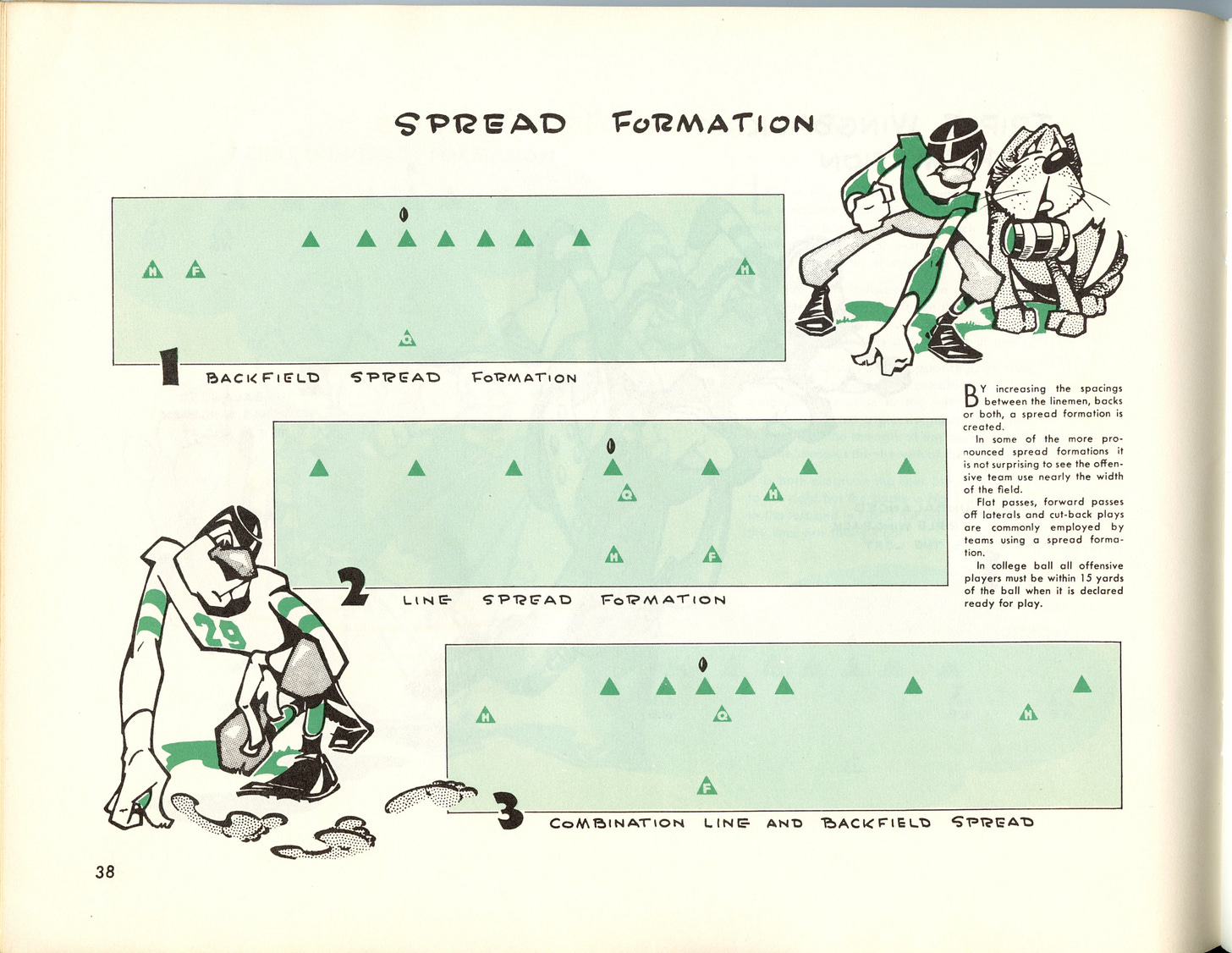

The last passing formation in the book was the Spread, which gained popularity with the San Francisco 49ers in the early 1960s and the Dallas Cowboys in the 1980s.

The Spread was born during the third year of the forward pass, when Idaho surprised its opponents with a crazy formation midway through the season. It then went dormant with teams employing it occasionally to surprise their opponents.

The college rules hampered the use of the Spread since all offensive players had to be within 15 yards of the ball at the snap. (The rule prevented shoestring and lonesome end trick plays that left a player standing near his team’s sideline who darted downfield for a pass following the snap.) Nevertheless, teams spread their linemen and their backs on occasion, sometimes catching the defense napping and winning games as a result.

There are a few more sections from Everybody’s Football that I’ll share in the coming weeks. I’m hoping to get back to more frequent tidbitting as I’m nearing completion of my next book, which covers the surprising story of the first decade of the forward pass. Look for it to be available early in the football season.

Football Archaeology is reader-supported. Click here to buy one of my books, donate, or otherwise support the site.

So fascinating. Great stuff