Today's Tidbit... Red Grange’s Forgotten Big Day

If you asked most football fans to identify the game Red Grange rushed for the highest number of yards in his college football career, most would say it came in 1924 when he gained 402 all-purpose yards against Michigan. That day began when he returned the opening kickoff 95 yards for a touchdown. As was common then, Michigan chose to kick off rather than receive after each Illinois touchdown, which allowed Grange to produce touchdown runs of 67, 56, and 44 yards in the game’s first 12 minutes. He had another rushing touchdown in the second half, threw a 20-yard touchdown pass, and intercepted two passes that afternoon. The Michigan game marked his highest all-purpose yard total in a college game, but his 212 yards rushing was not his top performance day. At least, that is believed to be the case, though the inconsistent statistics of the mid-1920s make it challenging to confirm.

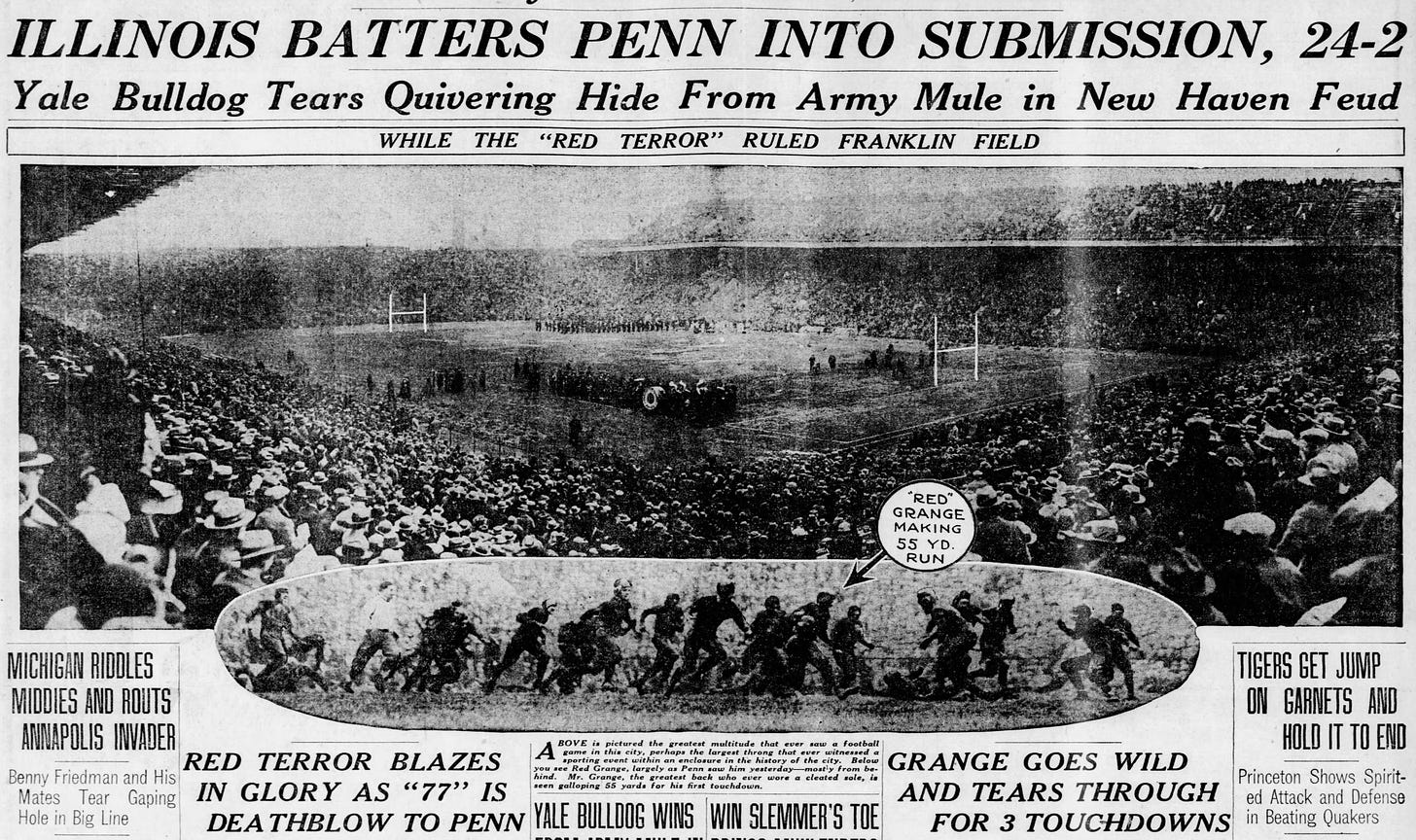

Some claim that Grange’s highest rushing total came when he picked up 237 yards against Pennsylvania during his senior year. Penn was 5-0 entering the 1925 game at Franklin Field in Philadelphia, having beaten two minor foes, plus Brown, Yale, and Chicago. Meanwhile, Illinois had not looked strong, beating Butler but losing to Nebraska, Iowa, and Michigan, so their 1-3 record left the Quakers looking forward to stuffing the Illini and Grange in a game played on a muddy field following a significant snowfall.

Other than playing at Syracuse in 1909, the Fighting Illini had not played farther east than Oberlin, Ohio, which lies west of Cleveland, and Grange had never been closer to the sunrise than Columbus, Ohio. Like now, the good people of Philadelphia graciously welcomed visiting teams, and while they certainly knew of Grange and his exploits, the tales of his talents were difficult to believe. The occasional newsreel showing his runs did little to convince them otherwise. Of course, it took only a few minutes of seeing him in action to change their minds.

The 63,000 fans in attendance were the largest crowd to attend a sporting event in Philadelphia up to that point, boosted by two trainloads of Illinois fans whose journey was delayed outside of Pittsburgh due to a wreck along the line. Penn agreed to start the game 10 minutes late, but the Illinois fans still missed the early action.

The game began with Grange returning the opening kick 30 yards, but the Illini soon punted, and then the Quakers followed suit. The excitement started on the first play of Illinois’ second possession. To that point in the season, Illinois typically ran to the strong side of its unbalanced Single Wing. When Penn’s defense overshifted to the strong side, Grange took the direct snap and ran to the weak side, finding a massive hole and cutting back across the grain as he ran untouched for a 55-yard touchdown run. The College Football Hall of Fame claims it was a 65-yard touchdown, and that he matched it with a second 65 touchdown run, plus a 13-yard touchdown run. The newspaper descriptions of the following day disagree about those distances, while agreeing that when Penn kicked off after Grange’s first touchdown run, he returned the second kick 65+ yards.

His third touchdown of the day came on a flea flicker, which was the original name for what we now call a hook and lateral. Ironically, the play combined elements of both plays. Coming near the end of the third quarter, Grange set up as the holder on a field goal attempt, with Britton, the left half, as the kicker. Upon receiving the snap, Grange tossed the ball back to Britton, who threw a strike to Kassell, the left end. Meanwhile, Grange was running left, and as Kassell caught the ball, he flicked it to the sweeping Grange, who ran untouched for the touchdown to make it 24-2 in favor of the Illini.

Given the lack of standardized statistics and rules, it is unclear whether Grange’s flea flicker yardage counted toward his rushing or passing totals. (They are passing yards today.) Grange left the game in the fourth quarter, but most accounts credit him with 36 carries to that point. The Chicago Tribune’s Harry Cross credits him with 363 yards on the day, though that likely includes the 95-yard kick return.

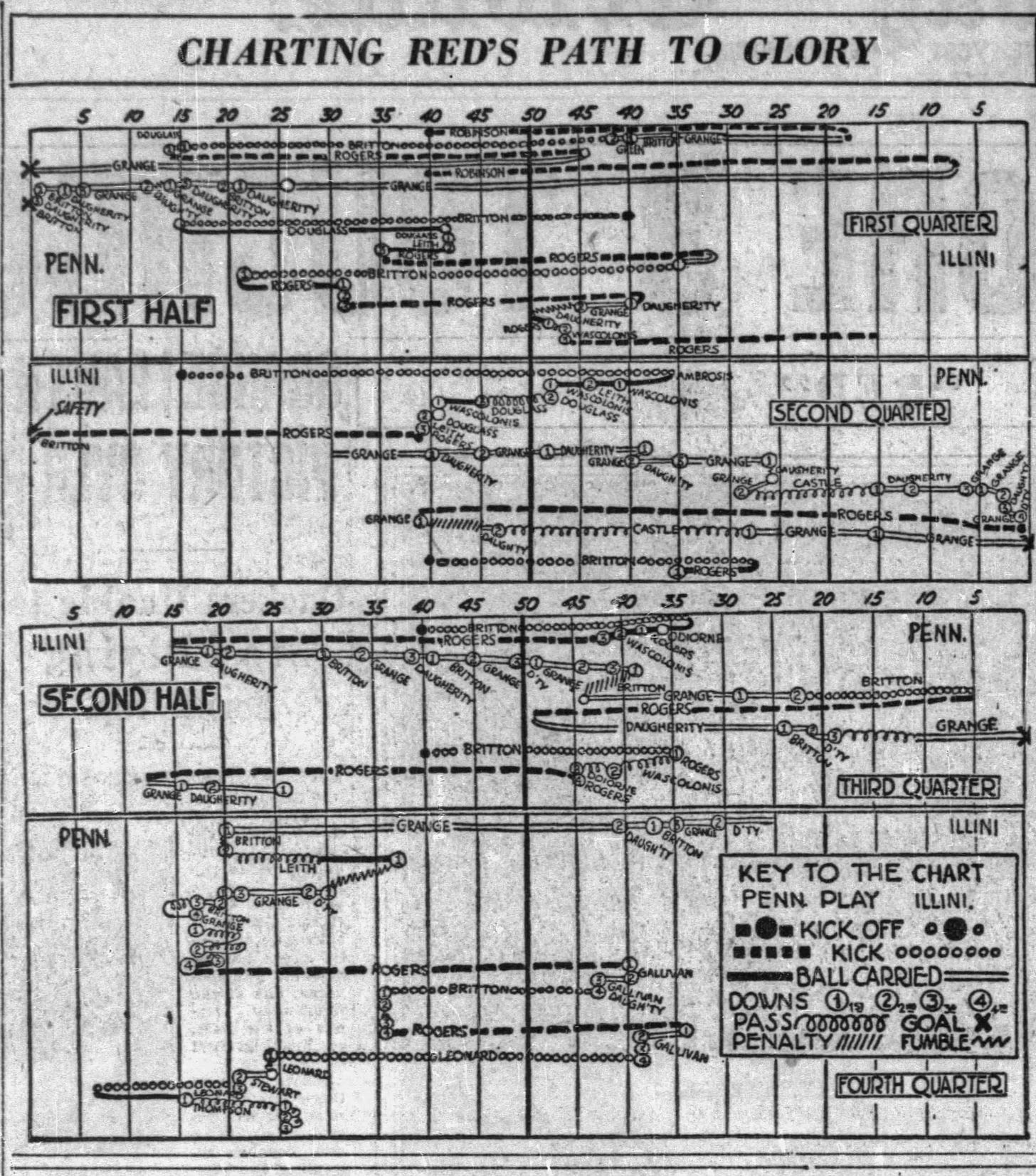

The Philadelphia Inquirer had Grange at 320 yards. That inconsistency led me to count Grange’s carries and yards based on the Chicago Tribune’s play chart published the following day. The ball carrier is sometimes not identified, and the yardage per carry is an estimate. However, I came up with 24 touches, 200 yards rushing, 12 yards receiving on passes, and 84 yards returning, for a total of 296 all-purpose yards, which differ from the newspaper totals.

Feel free to review my counts, as I may have missed some runs, but the old stats just were not trustworthy. Of course, questioning Grange’s stats on a given day does not detract from his performance and career. Instead, he delivered an incredible performance against Penn, as well as his performances against Michigan and Chicago (notably his 300 all-purpose yards) in 1924, all of which occurred in an era when offensive yards were scarce, reinforcing the incredible talent he brought to the game.

Football Archaeology is reader-supported. Click here to donate a couple of bucks, buy one of my books, or otherwise support the site.

Who wouldn’t want one or more of these books in their library? Get them here.

Love it! The Galloping Ghost and first football legend along with maybe Jim Thorpe… Achieved all time mythical status that few ever see.

A question: How do we count Grange's yardage after receiving the pitch on the flea flicker? Rushing yardage? Yardage after catch?