Today's Tidbit... Right- and Left-Handed Footballs

Balls are round, so we consider them equally appropriate for the right and left-handed among us. There are exceptions, of course. Bowling balls are handed for the right or left due to the opposable thumbs that some credit for many of the accomplishments in our sometimes-advanced civilization.

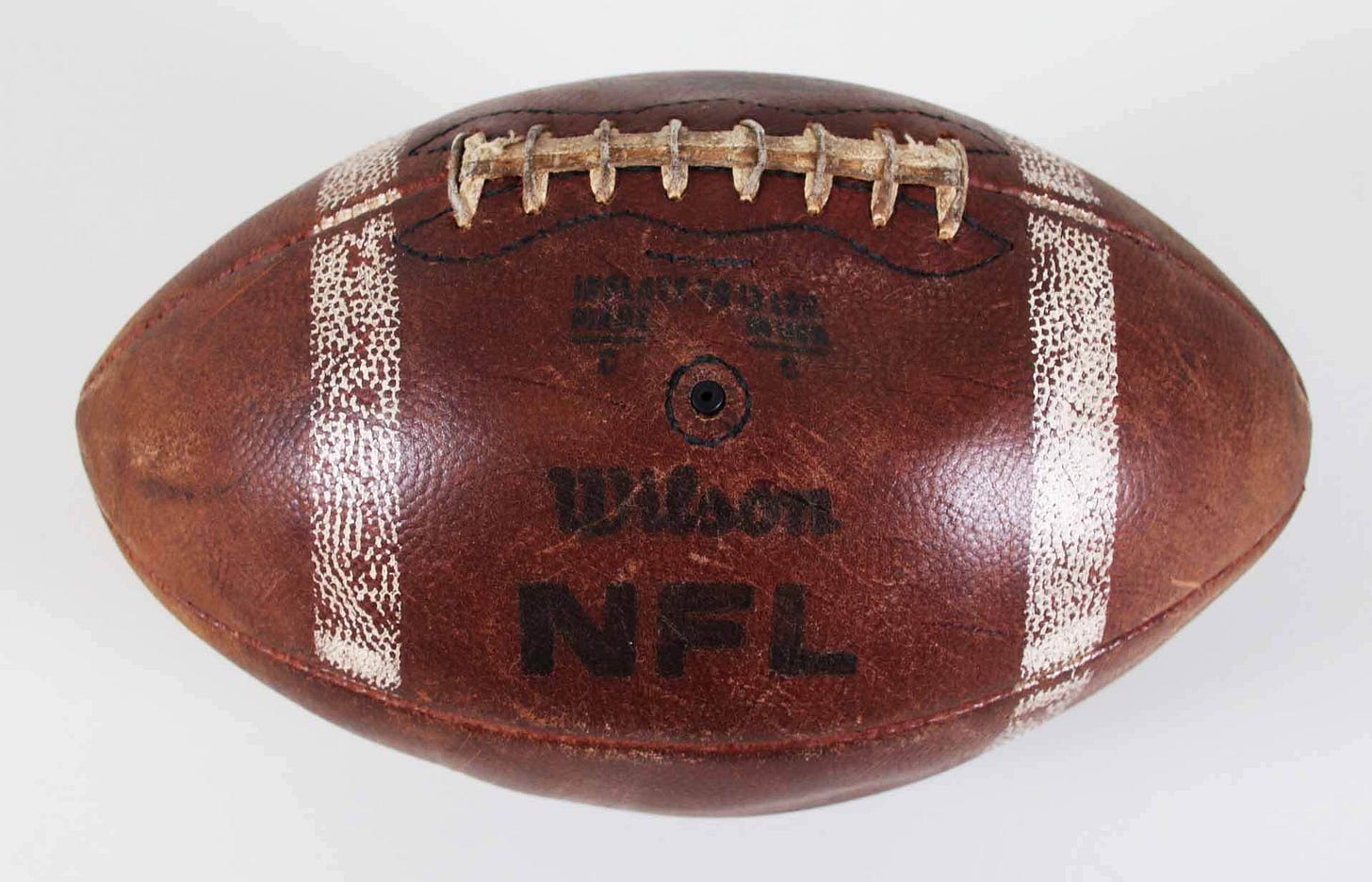

But bowling balls are not the only balls that have shown handedness. Footballs were right and left-handed for a time due to our opposable thumbs. I previously wrote about footballs being painted white or yellow starting in the early 1900s and gaining stripes in the 1930s due to the poor lighting conditions for night games. I have yet to cover the location of the stripes directly and how they led to right- and left-handed footballs, so here goes.

When the football first earned its stripes, the positioning of the stripes sometimes varied. Most models had 1-inch-wide stripes set 2.5 inches from the tip of the ball. Others had the stripe or stripes positioned differently. For example, MacGregor had their stripe positioned about 4 inches from the tip and overlapping the laces. Even their double-striped ball had the inner stripe in that position.

MacGregor might have moved the stripe closer to the tip since that is where they belong on red-blooded American footballs, but the more likely reason is that passers disliked paint on the laces because it made the ball slippery. Of course, that created more significant problems for the white or yellow balls.

During the 1950s, everyone settled on the tan ball with white stripes starting 2.5 inches from the tips, but those two white stripes encircling the ball still caused problems for quarterbacks whose thumbs rested on the stripes on the bottom of the ball.

Otto Graham complained about the thumb-on-paint problem as early as 1950, but no one did anything about it until the knife-wielding John Brodie began scraping the paint off the 49ers' night game footballs in the 1960s. (The NFL used balls without stripes for day games and tan balls with white stripes for night games until 1976.) Brodie's actions led the NFL to change its paint pattern by placing a gap in the stripe on the bottom panels where a right-handed quarterback's thumb rested. The broken-stripe pattern applied to both bottom panels because quarterbacks could grip one end of the ball or the other.

Unfortunately, the NFL's solution did not anticipate the arrival of Ken Stabler and Bobby Douglas in 1969 and 1970. Both were left-handed quarterbacks. While it does not appear that Bobby Douglas concerned himself with the striping, Stabler followed John Brodie's lead and scraped the paint off the ball where a left-handed quarterback's thumb rests. (Another version of the story indicates the Raiders' equipment manager did the scraping.) The situation led the Raiders' general manager, Al Davis, to persuade the NFL to order balls appropriate for left-handed quarterbacks. The NFL did so during the 1970 exhibition season by eliminating the stripe on the panel where a right or left-handed quarterback’s thumb rested and marking the left-handed balls with an "L." Thereafter, the officials ensured that right-handed balls were on the field for righty quarterbacks and left-handed balls were available for lefties.

The NFL solved the stripe problem for good in 1976 by eliminating the night game ball, and they have gone stripeless ever since.

Conversely, the NCAA approved tan balls with full white stripes in 1965. Then, the NCAA allowed the use of balls with stripes on two, three, or four panels in 1974 and required striping only on the two top panels beginning in 1975.

The final point about football striping is that the quarterbacks who play football in Canada seem not to be as affected by the fully painted stripe as their American counterparts since the white stripes encircle Canadian footballs.

Football Archaeology is reader-supported. Click here to buy one of my books or otherwise support the site.

Very interesting!