Today's Tidbit... Separating the Ladies and Gentlemen

Ordinarily, images of the crowds at football games are interesting because they indicate who attended games and the fashions they wore. The two RPPCs we'll review today are from the 1909 Oberlin-Heidelberg game and show us several other aspects of football crowds from the first decade of the twentieth century.

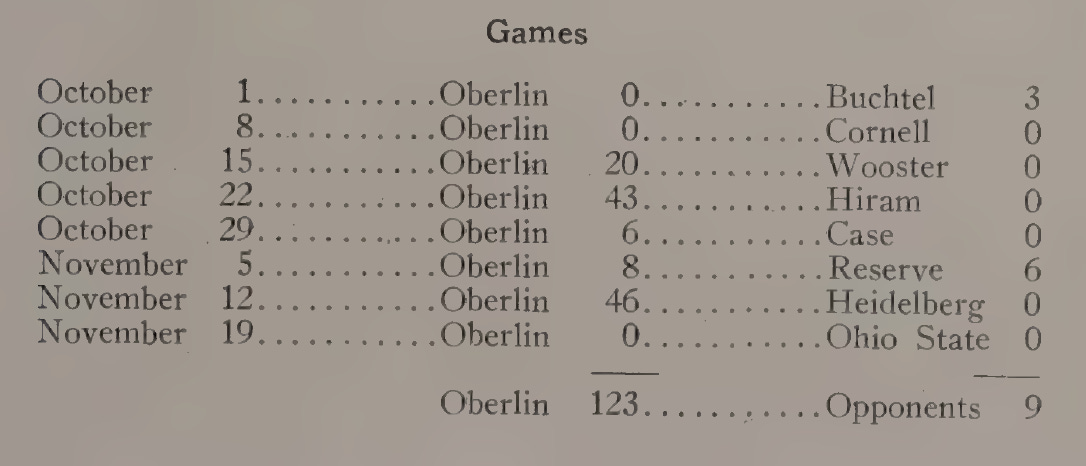

The image below shows Oberlin at home during the 1908 season, playing an unknown opponent. This image is not remarkable, but it shows that Oberlin football attracted good crowds during that period. They also played good football, as demonstrated by their 1909 record when they dominated most small-college opponents while tying Cornell and Ohio State.

Now, let's look at the crowd during Oberlin's second-to-last game with Heidelberg that season. The first shot shows a portion of the bench and those seated behind the fence near one of the 45-yard lines. The fans represent a wide age range; almost everyone wears a hat and tie. Overwhelmingly white, at least three college-age Black men are in the crowd. That was not the norm at most stadiums, but Oberlin was among the first U.S. colleges to admit Black men, and there were Black players on Oberlin's football team since at last 1891.

So while the stands were segregated by race at many locations, they were not at Oberlin. However, despite being the oldest coeducational liberal arts school in the U.S. and the second-oldest continuously operating coeducational institute of higher learning in the world, Oberlin's stands were largely segregated by gender. Segregation by gender was not unusual at the time, particularly among students.

The image below shows a section of the crowd -near the 5-yard line- occupied chiefly by women. Men are at the top, and a few mixed in here and there, but most people in the section are women, presumably students at Oberlin.

Many schools of the time were all-male or all-female, and some that were coeducational commonly separated their student cheering sections by gender. Northwestern, Texas, and Kansas did so to ensure the men in the crowd cheered lustily rather than turning their lustful attentions elsewhere.

A side effect of separating the men and women was the desire to have someone encourage the women's section to support their team, just as the male cheerleaders did with the men's section. The result was the election of Elizabeth Morrow to lead the Kansas women's section in chants in 1914, which made her the nation's first female cheerleader.

Football Archaeology is reader-supported. Click here to buy one of my books or otherwise support the site.