Today's Tidbit... Speaking Loudly and Loudspeakers

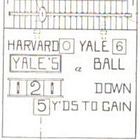

Football around 1900 involved two teams playing in close formations, often running the ball up the gut, so much of the game looked like a continuous goal-line stand. Players did not wear numbers, it was not uncommon for both teams to wear jerseys of the same color, and referee's signals did not exist, so fans often struggled to know who did what on the field. To enhance the fan experience, Arthur Irwin invented the football scoreboard, which was used in the stadium and at remote locations so fans could follow along with the game. By linking numbers posted on the scoreboard to players' numbers printed on scorecards, fans had a better idea of who did what.

Not every stadium could afford an Irwin scoreboard or the cost of all the people needed to follow the play on the sideline, transmit the information to the scoreboard, and update the scoreboard information following each play, so most stadiums stuck with the human voice or did nothing.

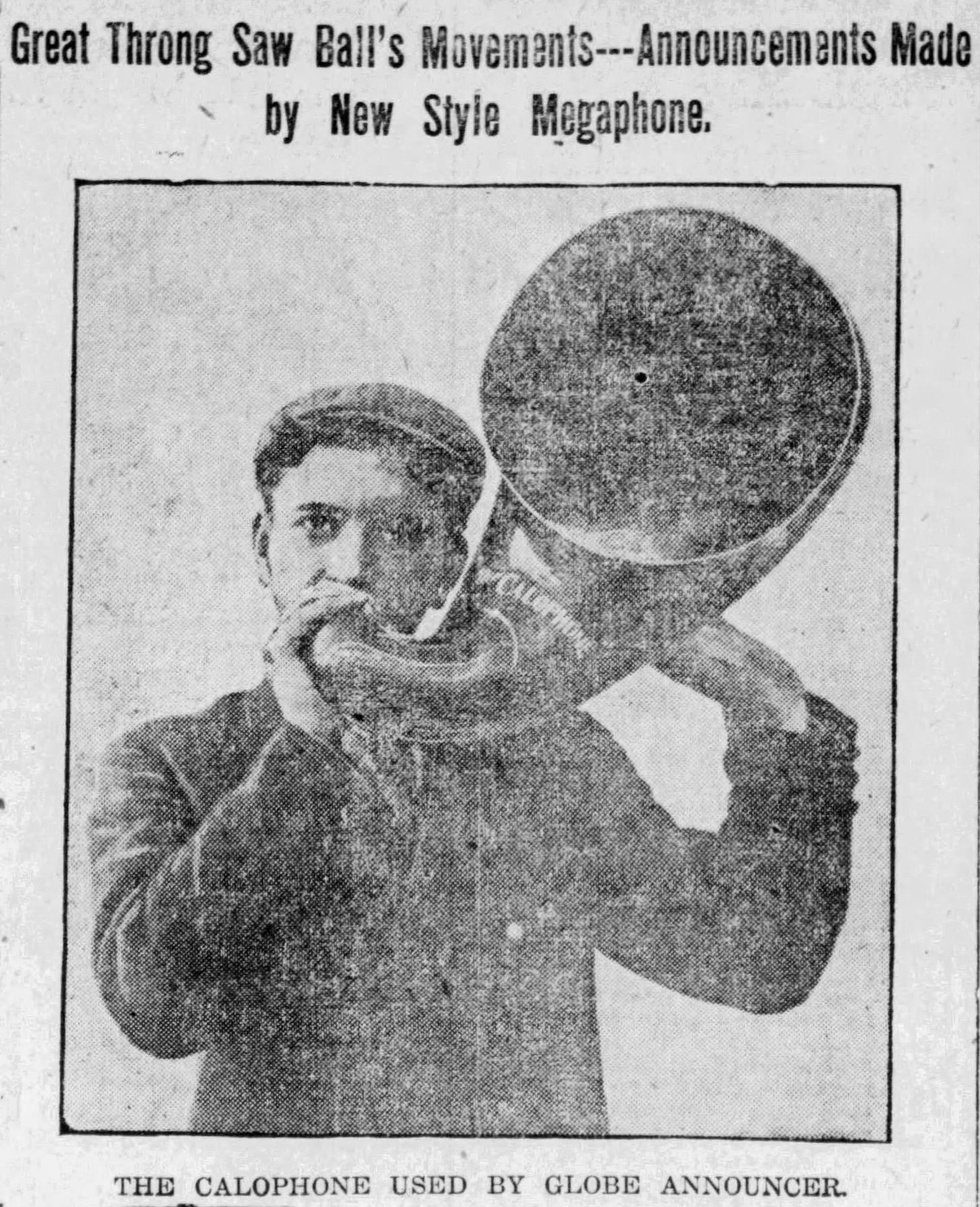

Other than some annoying neighbors, the human voice has limits, so the folks running stadiums supplemented the human voice with megaphones, and the earliest known to do so for a football game was at the University of Pennsylvania in 1893. A handful of other stadiums followed, and megaphones found use in subways with announcers in raised booths informing travelers which train was on which track. The nation's best minds sought to improve the megaphone and the delivery of sound, with the Calophone, a conch shell-shaped device, helping deliver the play-by-play of the 1906 Harvard-Yale game in New Haven to fans gathered outside the Boston Globe offices.

However, even the biggest and best megaphones had their limits, and a critical limit was their not being omnidirectional. They primarily cast their sound in the direction the announcer faced, limiting who could hear the message without the announcer repeating it in several directions.

The nation's best minds not working to improve the megaphone had their eyes and ears on the emerging telephone industry, which captured sound at one location, transformed those sounds into electric pulses, and sent them over copper wires in patterns that produced sound at the other end. Besides the standard telephone use, efficiency experts applied the technology in large auto factories, hotels, and train cars so the announcement could be made once and heard in many locations. Messenger boys running around hotels shouting guests' names and conductors passing through train cars announcing the next stop soon became a thing of the past.

The auto manufacturers appear to have been the first to apply the new technology to inform spectators at a sporting event when they installed 18 "transmitting diaphrams" at Brighton Beach Motordrome to make announcements during a motor race. Charles Ebbett, owner of the Brooklyn Dodgers, tested electric "enunciators" at Washington Park late in the 1912 season, while Charles Comiskey installed 69 enunciators at Comiskey Park in 1913 so fans throughout the stadium could hear the announcements and enjoy a bit of opera played between innings.

People stopped calling the electrical devices enunciators around 1920 as "loudspeakers" came into fashion. "Loudspeaker" and radio were synonymous early on, but by the mid-1920s, "loudspeaker" took on its current meaning and started to be installed in football stadiums. It's possible loudspeakers were used for football games played at Comiskey Park or other baseball fields that installed them, but the first mentions I found of enunciators or loudspeakers at football games were in 1923 and 1924.

The massive stadiums built during the stadium building boom of the 1920s required changes in announcement technologies, and they made that happen using the increased power of loudspeakers. The Rose Bowl installed loudspeakers in time for the 1924 game, and like many stadiums, it installed them on posts between the field and the stands.

Likewise, the 1924 version of the Los Angeles Coliseum, 24,000-seat Brookland Stadium at Catholic U., Minnesota's Memorial Stadium, and Missouri's Rollins Field all had loudspeakers installed. There were likely others.

Stadium loudspeakers went through their teething stages but eventually became commonplace, affecting other aspects of football, including playing The Star-Spangled Banner before games. Playing the anthem at sporting events did not arrive until WWI and then largely faded out, primarily because only a limited number of stadiums had loudspeakers, and the technology allowed only a limited range of sounds. As a result, playing the anthem required a marching band or similar, unassisted by the speaker system, to make it work.

Improvements in volume and sound quality following WWII allowed the use of prerecorded renditions or solo artists to perform the anthem, and it became common to play the anthem before most sporting events.

Click Support Football Archaeology for options to support this site beyond a free subscription.

My maternal grandfather was a reserve fullback on Washington's squad that tied Navy, 14-14-, in the 1924 Rose Bowl game, referenced in the post as the first Rose Bowl with loudspeakers installed.