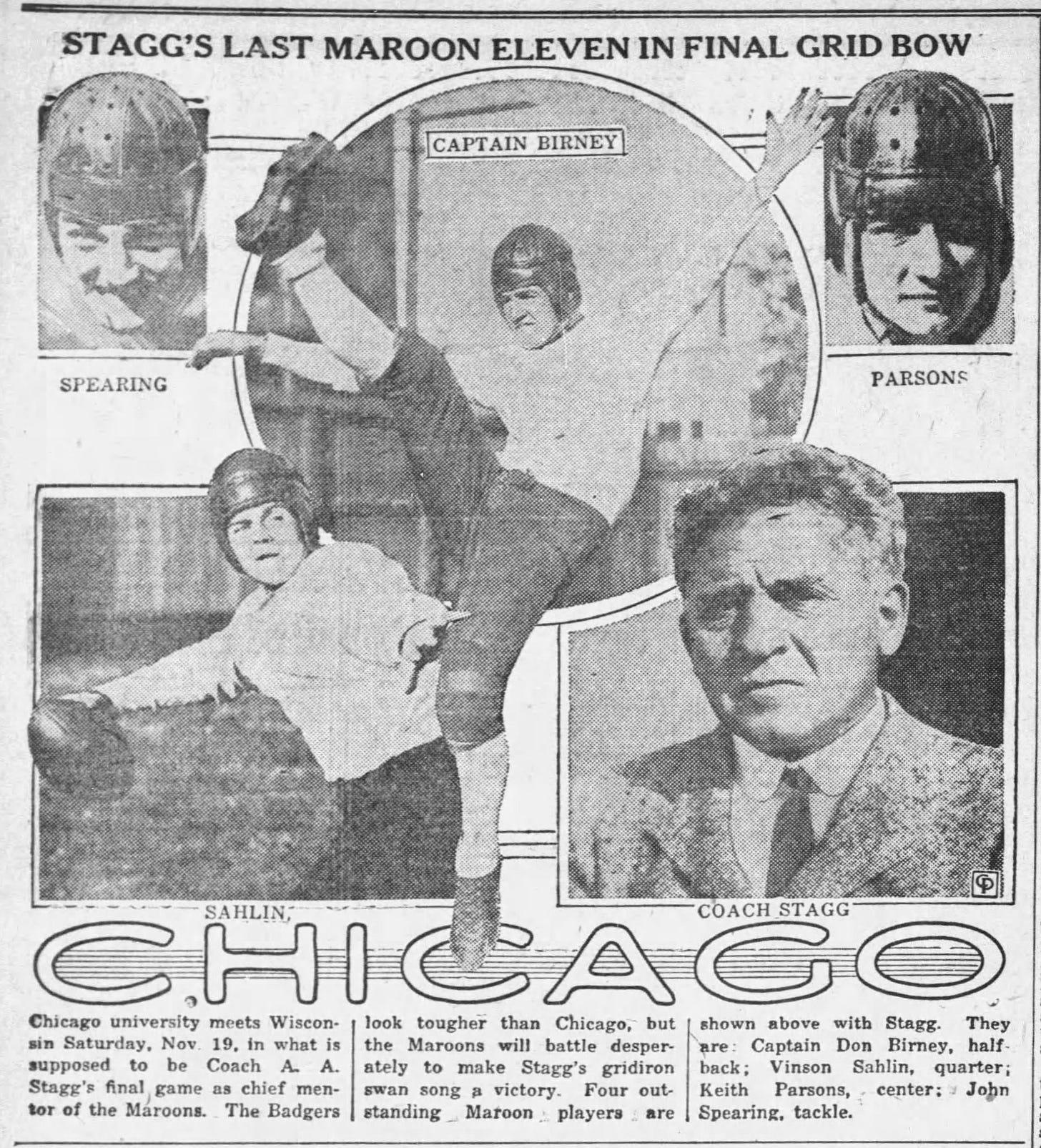

Today's Tidbit... Stagg's Last Game At Chicago

Walter Camp was born in 1859 and died in 1925 at age 65. Amos Alonzo Stagg came into this world in 1862, a few years behind Camp, and left it in 1965 at age 102, 40 years after Camp's death.

While both were pioneers of the game, Camp never saw hash marks, option football, WWII, or the rise of the NFL. Stagg saw all those things, plus plastic helmets, two-platoon football, and the start of football's broad embrace of Black players. Camp, the father of American football, witnessed only the game's first 50+ years, while Stagg, the uncle of American football, saw the first 90 or so.

Against that backdrop, we look today at Stagg's last game as coach at the University of Chicago in 1932. Stagg arrived at the Hyde Park campus in 1892, hired by the new university's president, William Rainey Harper, who had known Stagg while a faculty member at Yale. Stagg was the first world’s full-time physical education director and coach and was the model for all that followed him. Try as he might, Stagg could not beat back the hands of time or those of university president Robert Maynard Hutchins who viewed college football as a pain in the butt that interfered with the mission of the modern university. Hutchins deemphasized Stagg's budget and then struck with the dagger, forcing Stagg to adhere to university policy and retire at age 70 following the 1932 season.

Stagg was around for the Big Ten's founding and experienced a farewell tour during the 1932 season. His team started the season with a blowout of Monmouth (of Illinois), then headed to New Haven, where he tied Yale, his alma mater. Wins over Knox and Indiana left him at 3-0-1 in his final season, but Illinois, Purdue, and Michigan soundly beat his Maroons. To send him on his way, Illinois and Purdue, his oldest rivals, awarded him their school's letterman's blanket during their visits to Chicago’s Stagg Field. Michigan gave him a silver service the next week before Wisconsin gave him another blanket.

Sitting at 3-3-1, his final foe was a 5-1-1 Wisconsin team playing their best football in years under new coach Clarence Spears. Could Stagg pull off a final victory and earn a winning record in his 41st season on the Midway?

As the captains took the field, Stagg recognized the game's referee, Frank Birch, who had officiated Big Ten games since shortly after the forward pass came into fashion and had invented the referee's system of signaling penalties to the press and crowd.

As befitted Coach Stagg, the game proved to be one more field position-oriented, low-scoring game. The Badgers scored in the first quarter, leading one writer to note that "The Badgers scored in the first period with little difficulty." (If they had little difficulty, why didn't they score more than one touchdown in the first quarter?) Wisconsin missed the extra point attempt, so when the Maroons fought back, scored, and converted in the second quarter, they took a 7-6 lead. Even those who thought Stagg's best days were well in the past realized that he might pull off a final victory. Alas, a forward pass and lateral resulted in another second-quarter Badger touchdown and a 12-7 halftime lead.

Chicago fumbled a third-quarter punt on its 7-yard line, leading to another Badger touchdown, a missed conversion, and an 18-7 margin. Chicago was revitalized by a fourth-quarter punt return by Pete Zimmer, who eluded the Badger coverage and found himself running free when he tripped and fell on Wisconsin's 28-yard line. The Maroons had missed a sure touchdown and could not generate additional offense, so the score remained 18-7 until the final gun.

Stagg ended his final season at Chicago with a 3-4-1 record, leaving him with a 244-111-27 overall record, including 115-74-12 in the Big Ten, with 30 of those conference losses coming since his last championship in 1924.

Although Chicago had fallen under his reign, Stagg wanted to prove he could still coach, so he took the job at Pacific, where he coached another 14 years and, despite an overall losing record, won five conference championships by winning a handful of conference games against peer institutions in those years.

He then co-coached with Amos Jr. at Susquehanna for six years. Finally, he served as the kicking coach for a California junior college before officially retiring from coaching 26 years after Chicago gave him the boot and lost his last four Big Ten games.

Stagg was a fighter to the end. As he might have said, “Never give up, boys. Never give up.”

Football Archaeology is reader-supported. Click here to buy one of my books or otherwise support the site.