Today's Tidbit... Stanford Propelled By Airplane Drill

Football is a physical and inherently dangerous sport, so coaches have long sought ways to train their athletes and prepare them for the rigors of the game without risking injury in practice. Football equipment, such as tackling dummies and blocking sleds, allows teams to train without one athlete injuring another.

Approaching practice with a safety mindset was especially important at Stanford in 1919 since they dropped football after the 1905 season, playing rugby instead. Football returned in 1918 as part of the Student Army Training Corps program, but 1919 was their first varsity football season in 14 years. Evans had coached Colorado in 1916 and 1917 after a successful stint coaching Owensboro High in Kentucky after playing at Millikin (IL).

The Cardinal started the season 4-1, giving up six total points to the USS Boston, Oregon State, St. Mary's, and Santa Clara. In the second week of the season, they lost to the Olympic Club of San Francisco 13-0.

Stanford had two weeks to prepare for the Big Game with Cal., to whom they lost 67-0 in 1918. Cal also dropped football in 1906 but restarted in 1915, giving them a several-year advantage over Stanford in attracting and training football players. They also had one of the stars of the coaching profession, Andy Smith, as their mentor. Smith's California Bears also had a bye week before meeting Stanford, so the battle was on to see which coach could dream up the most innovative practice plans to prepare their team for the Big Game. However, no matter what Andy Smith had dreamed, he could not approach Evans in the innovation department.

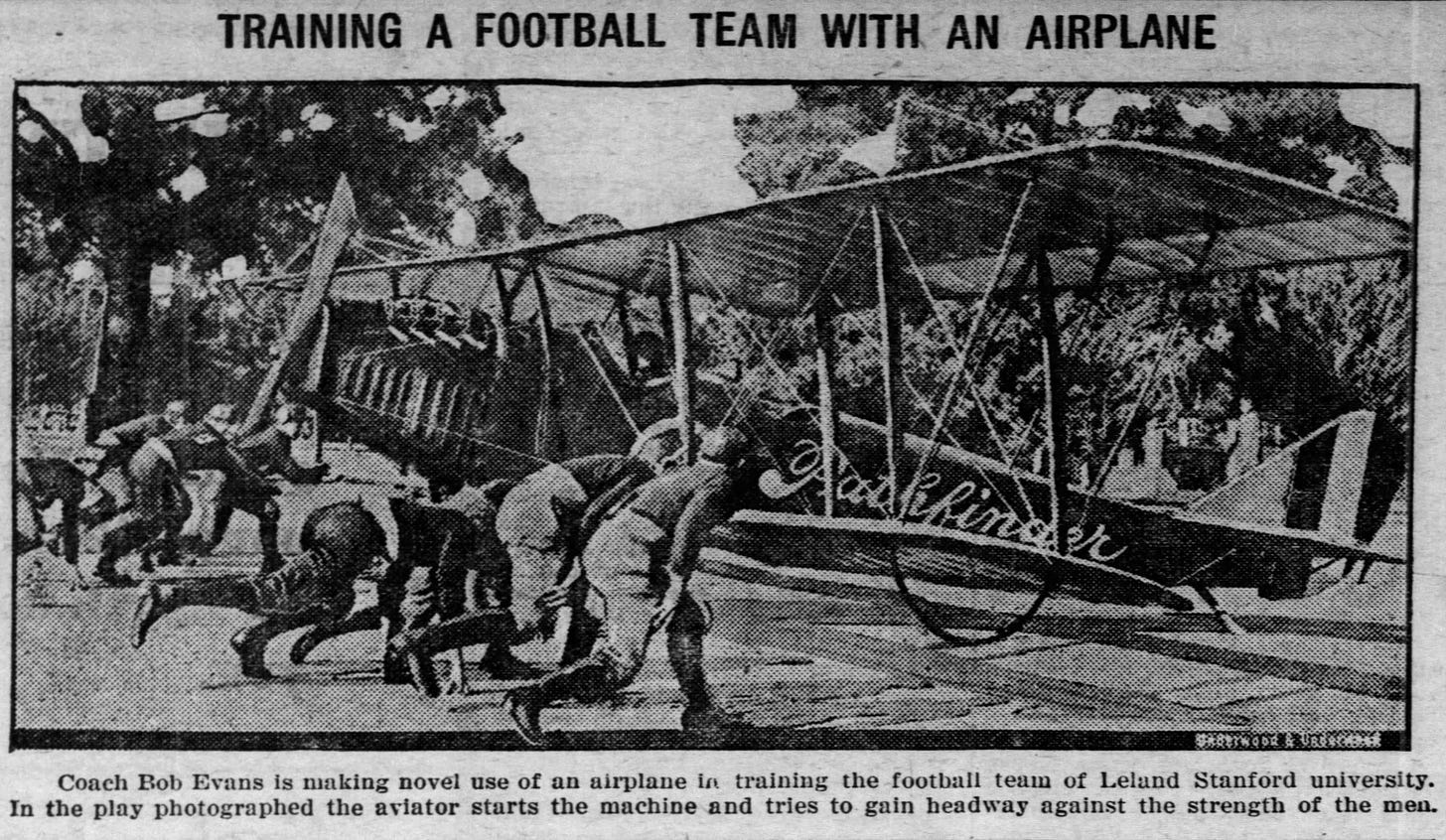

Evans developed a practice plan to condition his players like never before, even if it killed them. He did so with the help of an airplane and pilot, which he rented from the Pathfinder Aerial Transportation Company several afternoons each week. Each afternoon, the Pathfinder plane circled the stadium and landed on the gridiron at Stanford Field.

Once in place, the team executed two drills. In the first drill:

...the big machine is placed in motion, propellor started and the players placed along the wings. The aviator attempts to press forward against the strength of eight or ten men, but in the majority of the cases is unsuccessful.

'Stanford Grid Team Is Using Aeroplane To Do Training for Big Game,' San Francisco Bulletin, November 17, 1919.

The second drill integrated fumble recovery and tackling when:

The ball is thrown in under the machine while the propellor is going full speed and the ball is swiftly thrown by the current along the ground.

One player remains directly in back of the plane, while the others stand several yards in the rear. As the ball comes out the player near the plane grabs it and starts a dash down the field. His teammates then fall, very unceremoniously on the first player and the tackle is completed.

According to Evans, his Stanford players showed significant improvement after he initiated the drill, and he confidently predicted the airplane drill would become a standard element of football practices moving forward.

... the training does more good than harm and there is no question in my mind but what airplane training will soon become a big factor in the conditioning of players for battles such as we expect from California.

Stanford lost to Cal 14-10 and then to USC 13-0 on Thanksgiving.

Evans coached Stanford's basketball team that winter and the baseball team the following spring, and that appears to have been the end of his coaching career.

Likewise, his airplane drill never took off, or at least no high-flying coach admitted to using it in their practices.

Football Archaeology is reader-supported. Click here to buy one of my books or otherwise support the site.

Stanford really had to "wing" it with practice drills. Great story