Today's Tidbit... Starkey Seminary and the Binghamton Snowbank

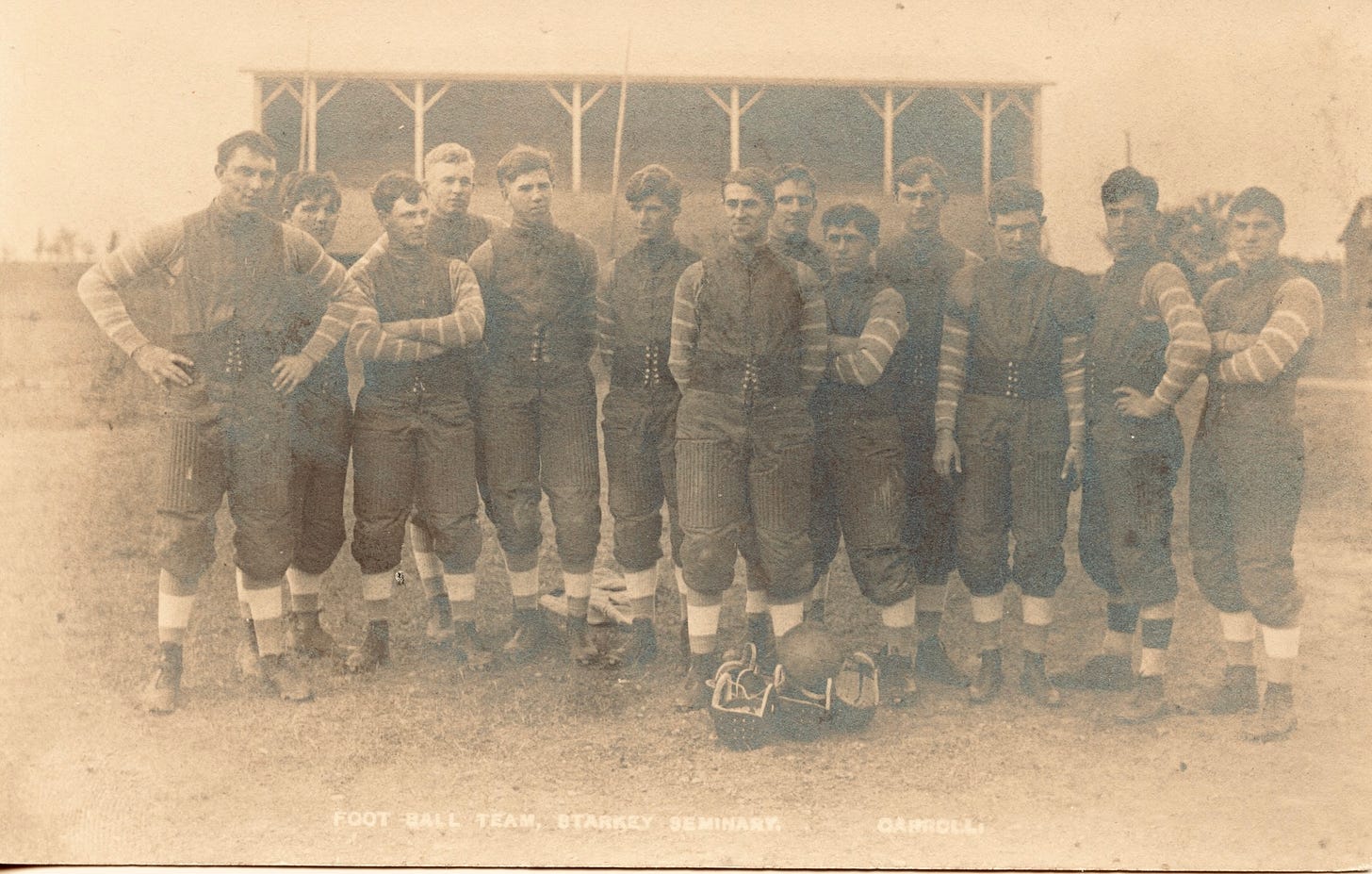

Sometimes, giving 110 percent provides benefits. Recently, I gave 110 percent, even 115 percent, effort when I saw an RPPC for sale that showed an undated but c. 1905 football team representing Starkey Seminary, a school on Seneca Lake in New York's Finger Lakes region. The school closed in 1936, in the aftermath of its endowment disappearing in the 1929 stock market crash caused by greedy billionaires and inadequate regulation.

Before losing the endowment, the school was well funded, as shown by the quality and consistency of the football team's uniforms. Every player has the same striped-sleeve jersey, identical vests, and elastic cummerbund to prevent opponents from grabbing the top of the pants when tackling Starkey players. Everyone also has the same socks except the second guy from the right.

So, what was the Starkey Seminary, and who were these guys? Before bidding on the RPPC, I searched a bit and almost immediately found a 1907 newspaper article showing the same image as the RPPC, so I knew who they were when I bid, but I did not dig further until I won the item. Still, I figured if giving 115% effort resulted in a lucky identification, giving 120% effort when researching the team might reveal a story worth telling.

As best I can tell, Starkey Seminary had about 300 secondary students, including boys and girls. Like many schools of the sort, some students were postgraduates, including athletes, who took an extra year to improve their scholastics before applying to college. Sharkey's postgraduates were a point of contention among the high school opponents they beat.

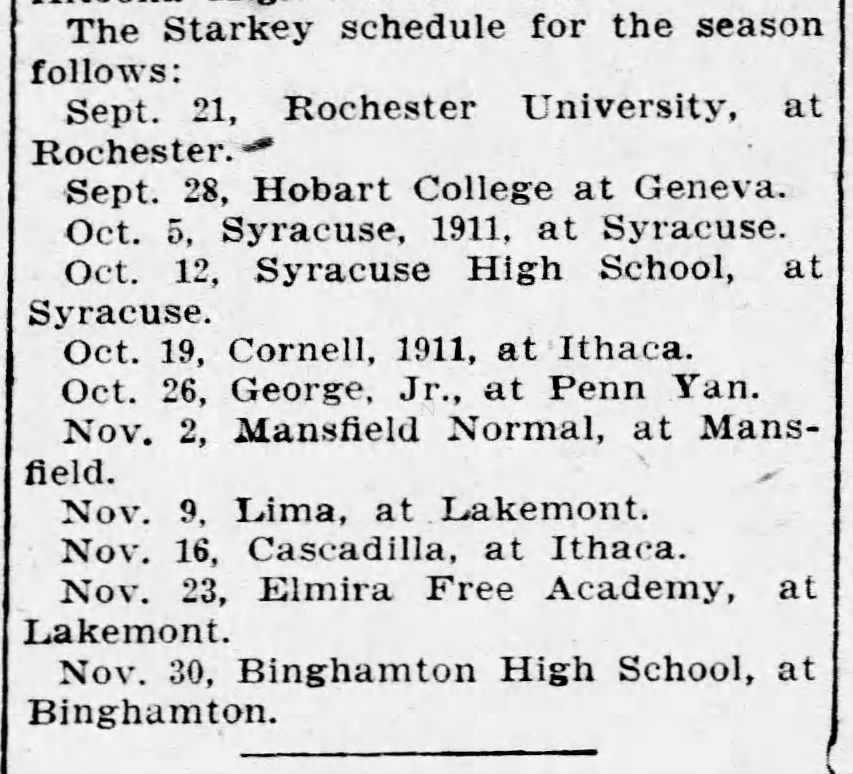

Being located in the middle of nowhere, Starkey traveled across western and central New York State, even Pennsylvania, to find competitive opponents, and they scheduled aggressively.

Starkey's schedule had them opening the season playing two college teams, and they had Mansfield State in the seventh game. They also had games with the Syracuse and Cornell freshmen teams, plus six high school teams from larger cities in the area. As often occurred at the time, games were canceled by one team or the other, and they picked up a few substitutes.

According to the available news reports, Starkey suffered their first loss when Hobart scored on a fluke play to win 6-0. The next reported game saw them travel to Ithaca to face Cornell's freshmen team, who they beat 5-4 by throwing a "double forward pass," the period term for a forward pass following a reverse in the backfield

Starkey then beat an All-Corning team 38-0. Corning, a city near the Pennsylvania border, likely fielded a team that included recent high school graduates and others. A loss to Rochester West High followed before they met their rival Elmira Free Academy, who they beat 23-0.

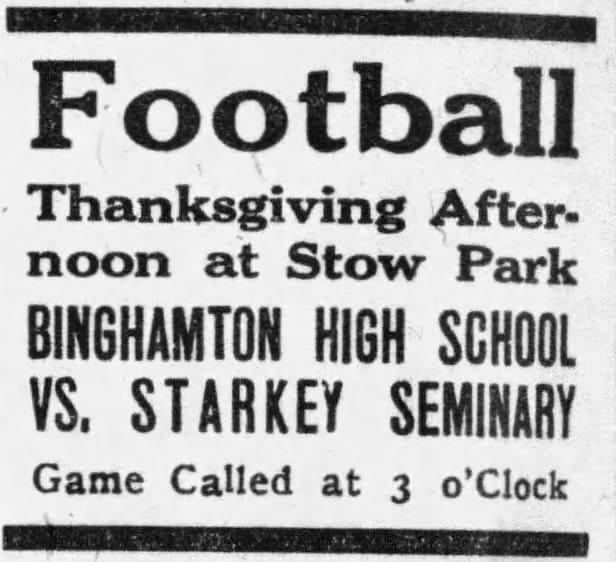

The season ended with a Thanksgiving Day game against Binghamton High, which was undefeated in 1906 and 1907.

As happens in central New York State, it snowed in Binghamton the day before the game, and since they played the game in 1907, football fields did not yet have end zones, and forward passes could not legally cross the goal line. So, when the Binghamton grounds crew shoveled the field, they tossed the snow just past the goal line, creating a big snow pile there.

During the game's first half, Starkey moved the ball inside Binghamton's 5-yard line, literally allowing the snow pile to come into play. Binghamton's stingy defense kept Starkey from scoring on third down, so possession went to Binghamton. Opting to get themselves out of trouble, Binghamton chose to punt, which meant their punter had to stand behind the snow bank, receive the center's snap, and punt the ball down the field. Apparently, Binghamton had a pretty good punter, since he caught the ball and booted it nearly forty yards downfield, keeping Starkey from scoring in the first stanza.

Despite Binghamton's special teams' ability to punt over snowbanks, Starkey enjoyed good fortune from their kicking game late in the second half when a Binghamton player nearly blocked Starkey's 25-yard field goal attempt. Thankfully, the ball avoided the flying Binghamtonian and headed toward the goal before striking the crossbar and bouncing over to give Starkey a 4-0 victory. (Here’s a similar story about punting from behind a barbed wire fence.)

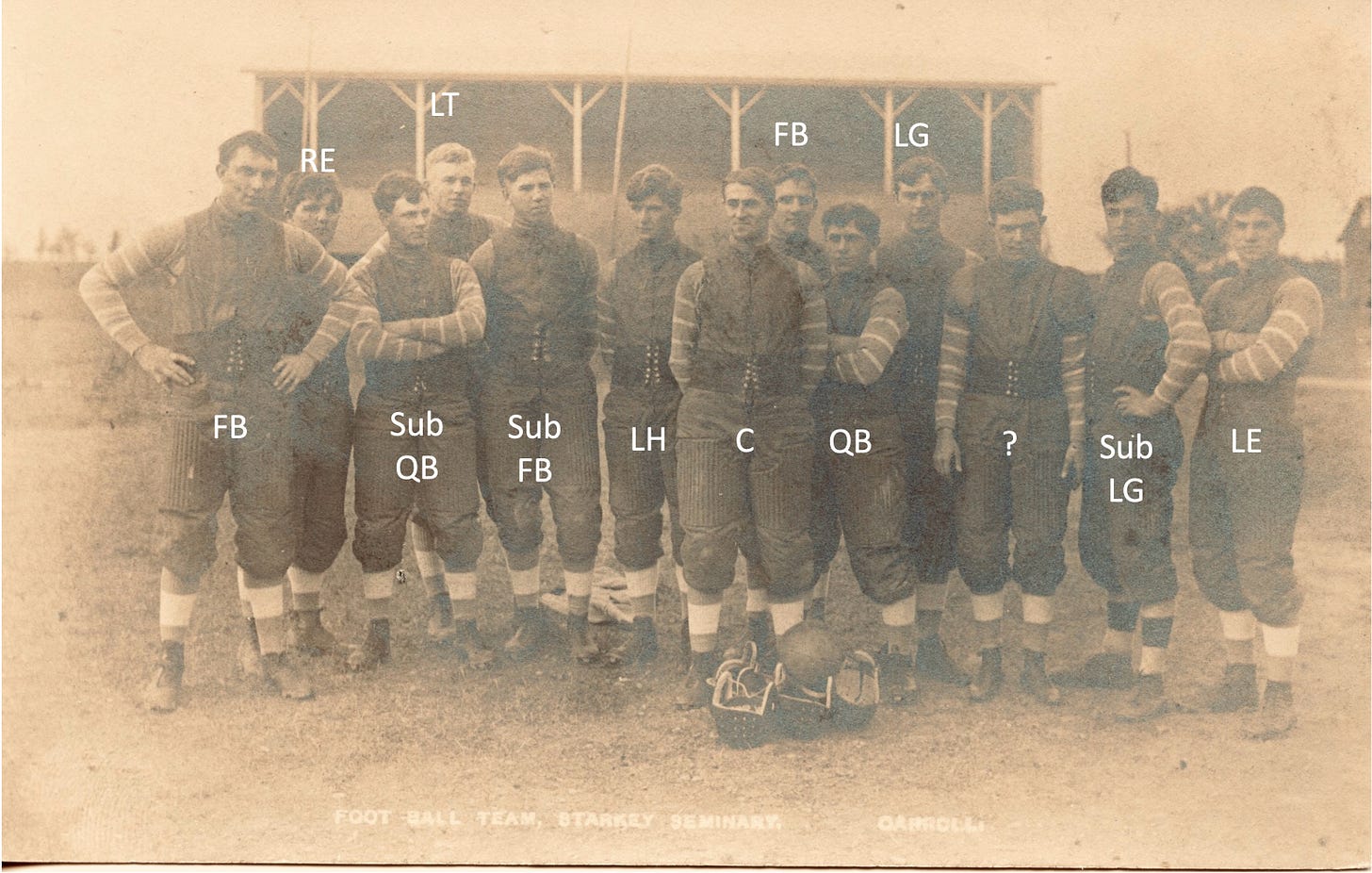

To end this story, I decided to identify the position of each pictured player. The table below shows the players listed in order (left to right) and their starting or substitute positions (in gray). Bashford started every game but is not in the picture, while Robinson is pictured but did not play.

Five players' names were spelled inconsistently, as was common in days before mimeographs, photocopiers, and computer printers. Back then, reporters learned players' names verbally and scribbled them down as they heard them, leading to misspellings and inconsistencies, which are the bane of those tracking football players 100+ years later.

My fourth blog post ever in 2017 discussed the challenges inconsistent names caused when tracking the 178 men I identified as part of the 1918 or 1919 Rose Bowl teams. The story is supposed to be humorous and remains among my favorites.

Take a look if you have the time.

Note: Last week I said that I would hold a drawing among paid subscribers for six $50 Homefield gift certificates. I notified the selected subscribers by email yesterday.

Click here for options on how to support this site beyond a free subscription.