Today's Tidbit... Taking A Position on All-American Teams

One way to look at the history of football is by reviewing the positions named to the game's All-America team, which began when Caspar Whitney identified the nation's top players at each position for the 1889 season. Whitney named eleven players representing three schools: Princeton (5), Yale (3), ), and Harvard (3). The eleven players included two ends, tackles, guards, halfbacks, and one center, quarterback, and fullback. That is how things remained until 1949 or 1950, depending on who you ask.

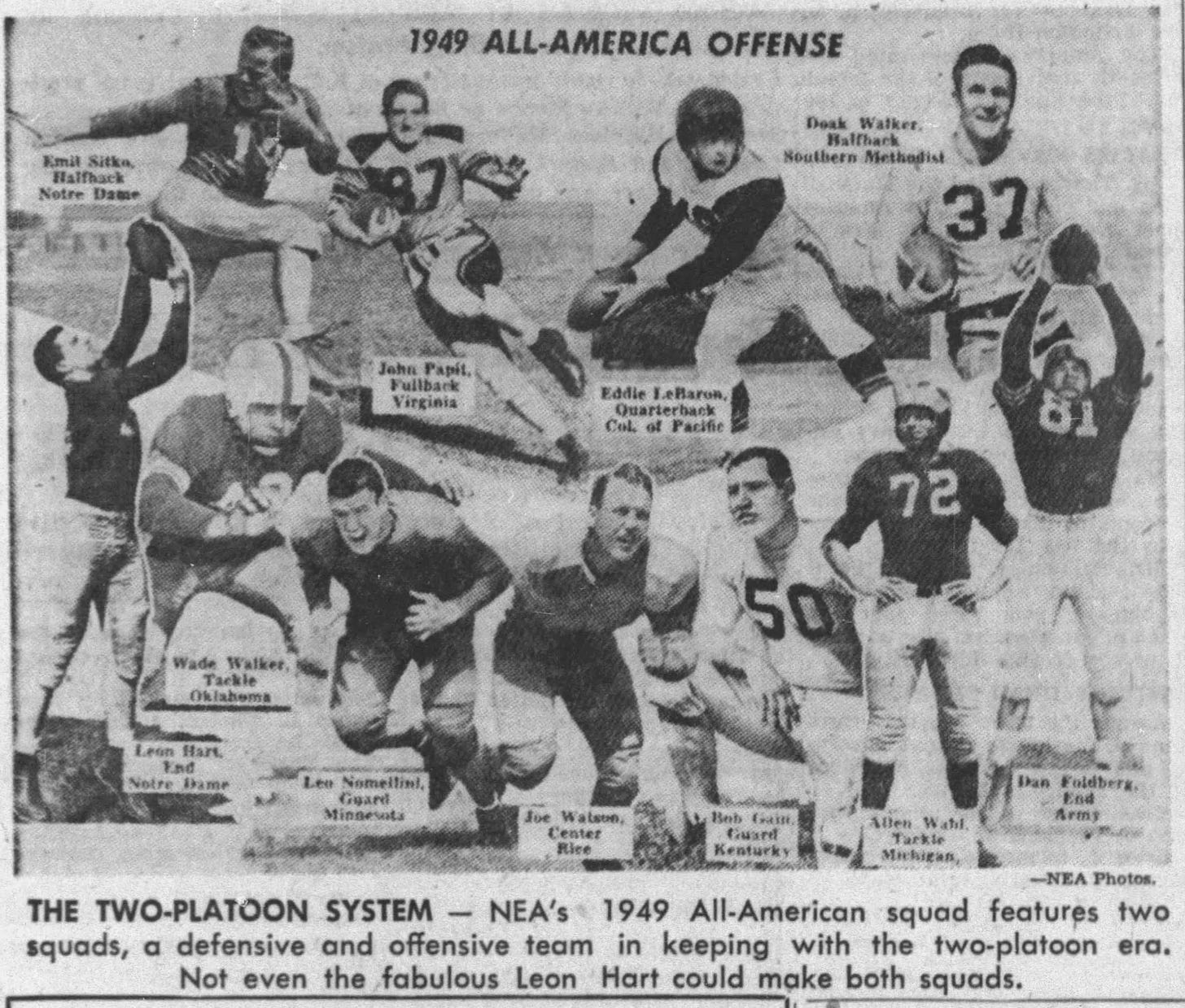

Football stayed a single-platoon game until 1945, so the All-America team did not need more than eleven players. Until then, some players earned their spots for their offensive prowess, others for their defense, and others because they punted or kicked the ball well. The onset of platooning led the Newspaper Enterprise Association (NEA), one of the top news syndicates, to name separate offensive and defensive All-Americans in 1949.

The offensive players manned the same positions Whitney identified seventy years earlier, but which positions comprised the defensive All-Americans team in 1949? The NEA named a 6-2-3 defense with two ends, tackles, and guards, two "line backers," two halfbacks, and one safety.

The Associated Press (AP) named offensive and defensive teams in 1950, as did the United Press International (UPI) in 1951. However, college football's return to single-platoon football in 1953 meant the All-American teams also returned to singularity.

College football slowly eased its substitution rules in the 1950s, with the pace picking up in the early 1960s. By 1964, the All-American team returned to two-platoon affairs, but the positions evolved somewhat. For example, NEA's offensive team lost a back but gained a flanker, so the team had two ends, one flanker, two tackles and guards, one center, one quarterback, and two running backs. Meanwhile, the defense shifted to a 5-3-2 look with two ends, two tackles, one middle guard, three linebackers, two halfbacks, and a safety. The following year some players earned All-American team status as tight ends.

The influx of soccer-style kickers in the 1960s spotlighted the game's specialists. That led The Sporting News, which was not recognized by the NCAA as naming an official All-American team, to become the first to name kickers and punters to their team in 1966. Others followed suit, though the AP specialized in ignoring specialists until 1981.

With the increased variation in defenses, the mid-1980s saw the end, tackle, and middle guard positions collapse into a general defensive line category on some teams. The change allowed the naming of the best defensive linemen to the team regardless of the scheme in which they played or the amount of high-end talent at a particular position. Also joining the fray was another special teamer, the return specialist.

The 1990s saw more All-American teams separate cornerbacks from safeties. Still, like other situations in which independent organizations made of writers, coaches, and others seldom were they consistent in their approaches.

Despite the explosions in offensive and defensive approaches over the last twenty years, the team structures have seen little change. This lack of movement makes more sense on the offensive side of the ball because the rules dictate seven men on the line of scrimmage, with the outermost being eligible receivers, so seven of eleven offensive positions are significantly defined by the rules.

That is not the case with defenses, where the rules do not dictate alignment and function. The shape-shifting defenses that now play two to four down linemen, hybrid linebacker-safeties, or six defensive backs may require future All-American teams to alter the number of players chosen by "position." Perhaps fewer defensive linemen will become All-American while the number of defensive back increase. As has occurred in the past, individual players will likely redefine particular roles in the future, and the All-American teams will catch up a few years down the road.

Football Archaeology is reader-supported. Click here to buy one of my books or otherwise support the site.