Today's Tidbit… The 1933 Rules Committee And The Future of Football

Regular readers of this site and other intelligent people know that American football has often faced conflicts over the game's direction. Today, the primary disputes in college football are player safety and money. Some see targeting and other rules intended to eliminate dangerous hits as at odds with the aggressive play they consider central to football. Likewise, college football’s transfer portal and NIL move the game into territory many do not like. Regardless of where you stand on either topic, both revolve around fundamental beliefs about how the game should be played and the rewards for doing so.

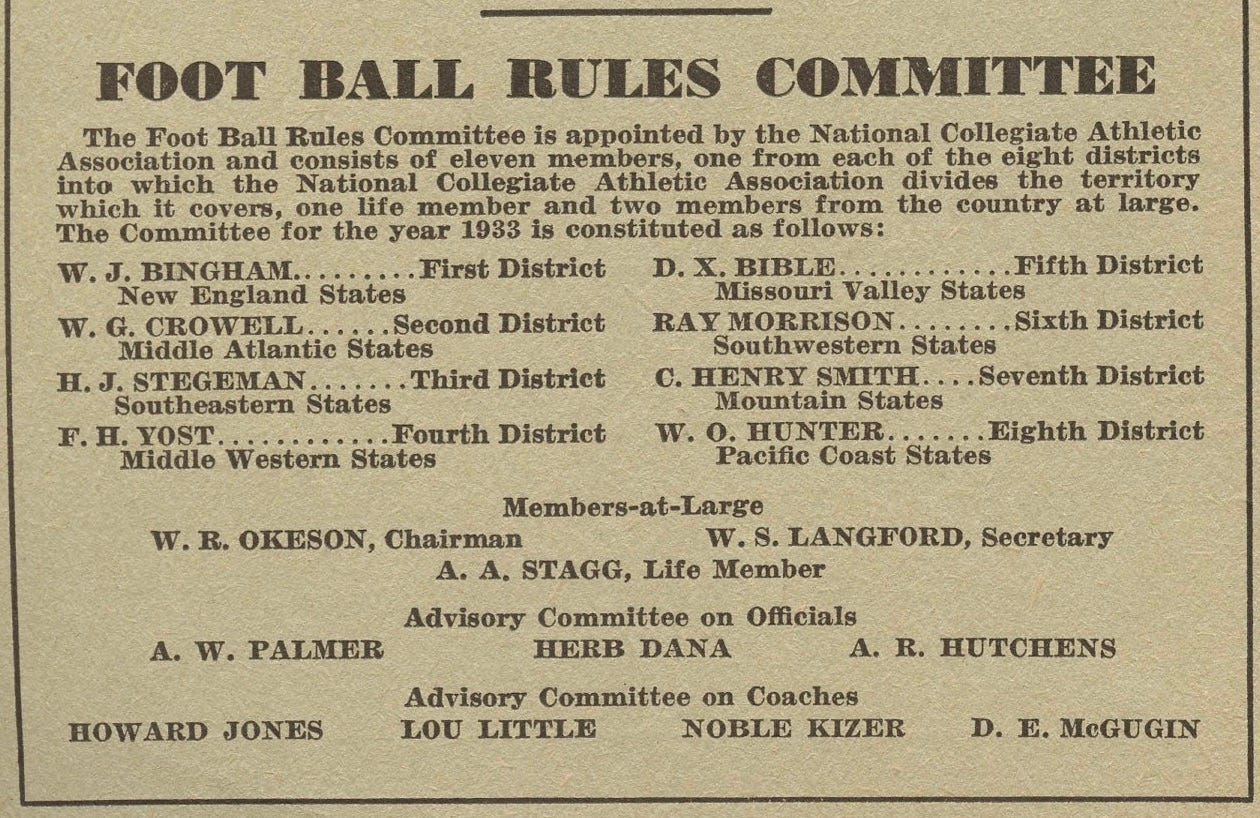

Like others before and after, the 1933 rules committee and coaches generally faced battles over core beliefs about the game, with theirs concerning the balance between offense and defense. Many wanted to tilt the rules in favor of offensive play and increase scoring, and the conflict was exemplified by the fight over penalties for incomplete passes. Starting in 1926, teams could legally throw only one incomplete pass in a series of downs. A second incompletion resulted in a five-yard penalty. Although the rule seems silly now, its intention was to keep trailing teams from flinging the ball around the field and earning a “cheap” touchdown. They believed real teams earned touchdowns the old-fashioned way - by running it and playing the punting-field position game.

Some, like Columbia's Lou Little, wanted stiffer punishment for the ball flingers, seeking to increase the penalty for the second incompletion from five to ten or fifteen yards. On the opposite side were those pushing to eliminate the penalty for incomplete passes. Not only that, but Northwestern's Dick Hanley wanted passers to be able to throw the ball from anywhere behind the line of scrimmage, eliminating the rule requiring passers to throw from at least five yards back of the line of scrimmage.

Pop Warner came at the problem from a different angle. Never a big fan of the forward pass, he hoped to improve football by enhancing the running game, proposing they limit defenses to six men on the line of scrimmage. Presumably, Warner’s rules would allow offenses to more easily run the ball, as God and Walter Camp intended.

As it turned out, none of those rule changes made it through the 1933 rule-making process. However, the penalty for throwing a second or third incomplete pass in a series of down went away the next year, and the requirement that passes were thrown from at least five yards behind the line of scrimmage disappeared in 1945.

Still, the 1933 committee moved forward with one significant rule change. They added inbound lines, aka hash marks, which ensured teams no longer snapped the ball while pinned against a sideline. Adding hash marks proved a more significant change than the committee anticipated, but approving the hash mark rule signaled growing support for liberating offenses, and football increasingly shifted to a more wide-open, higher-scoring game. Soon, Dutch Meyer and other coaches in the Southwest took advantage of these rule changes to introduce more sophisticated passing offenses to the game.

The shift in orientation to liberalize offenses in the 1930s produced a more exciting, crowd-pleasing game. Looking to make money, the professional game took this approach to heart while the colleges continued battling over whether football was a money maker or a learning experience for the players. The orientation difference helps explain why the NFL came to dominate the spectator side of the football industry beginning in the 1950s.

Football Archaeology is reader-supported. Click here to buy one of my books or otherwise support the site.

Thanks. It was fun to work on.

This one is especially well-written, Tim! Terrific work...