Today's Tidbit... The Flying Wedge and Horse's Neck

Lorin Deland, a Bostonian and student of military tactics, borrowed from military tacticians of the late 1800s by creating football plays using miniature figures set up on a tabletop football field. One output of his tabletop generalship was the Flying Wedge, which remains among the game’s most famous designed plays. Harvard sprung the Flying Wedge on Yale when they kicked off to start the second half of their game in 1892.

Harvard had run many inside wedges from scrimmage during the game’s first half, but the Flying Wedge brought real momentum to the game. At the time, the norm was for teams to retain possession when kicking off. Like today’s soccer teams which open the half with one player kicking the ball to a teammate, football halves of old opened with the kicker dribbling the ball a few inches, picking it up, and tossing it to a teammate who ran with it.

Harvard's Flying Wedge expanded on that approach by aligning two groups of five players behind and to either side of the kicker. On signal, they ran toward the kicker, who dribbled the ball, picked it up, and gave it to a teammate who ran behind the wedge running full speed toward Yale.

The first Flying Wedge worked beautifully until the runner fell after gaining fifteen yards. Harvard was forced to punt that possession. When they regained possession, they used the Horse's Neck, a "series" of plays designed by Deland. A series is a set of plays with similar movements, so each play looks like the next, and disguising which player receives the ball. For example, the Wing T's backfield movements are identical for the dive, sweep, and waggle, regardless of who gets the ball.

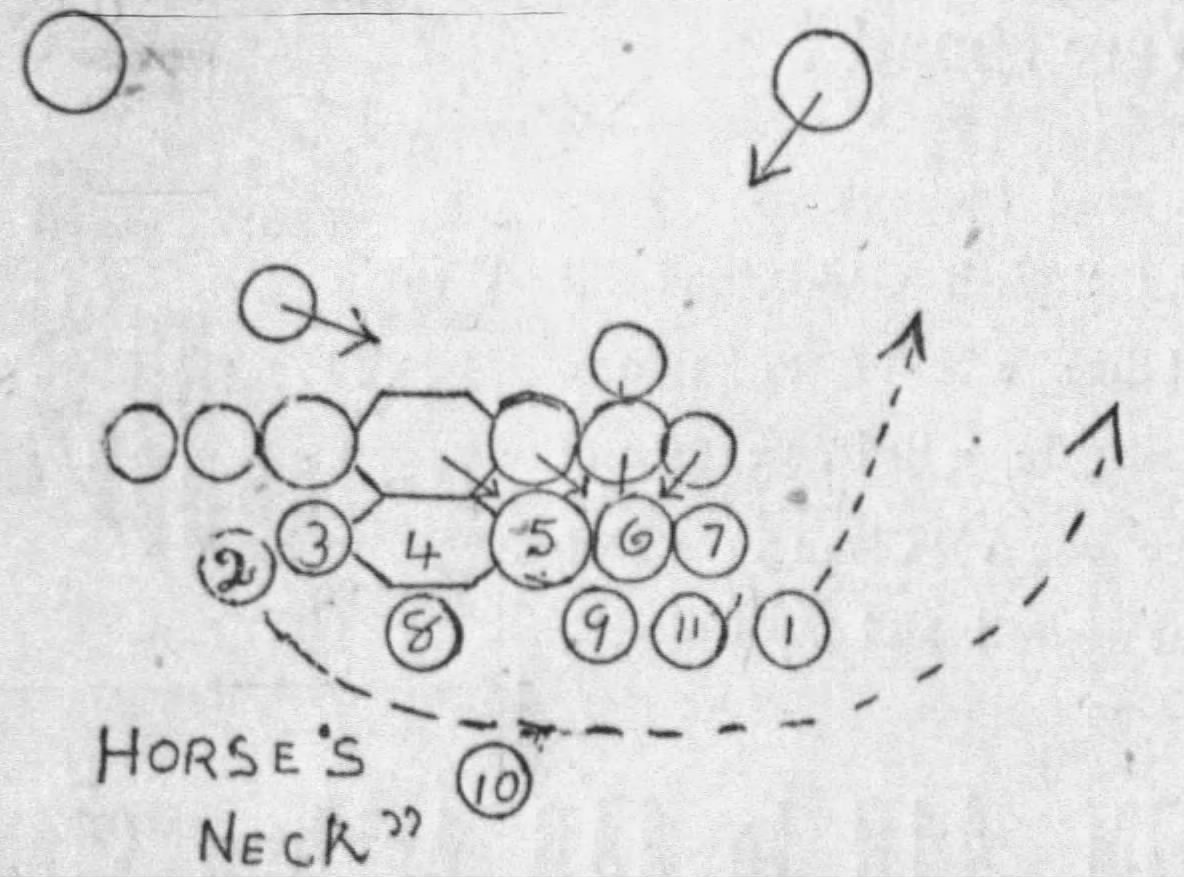

Series plays are fundamental now, but they had to start somewhere, and the Horse's Neck was among its beginnings. Here’s how it worked. The drawing below shows Harvard on offense over-shifted to the right, positioned to run yet another wedge to the right side.

Ignore the movement of the left tackle (2) for now because he stayed in the line and blocked in the version of the series they ran on first down. Harvard lined up as shown on first down, snapped the ball to the QB (8), who tossed it to the fullback (10), who ran into the wedge over the right tackle (6), gaining five yards.

On second down, Harvard lined up in the same formation and faked to the fullback running into the wedge once again. Frank Hinkey, Yale's aggressive four-time All-American end, flew inside to stop the wedge, only to find the fullback did not have the ball. Instead, it was in the hands of the left tackle (2), Upton, who swept around the right end for a 23-yard gain.

Running a sweep after faking a dive into a wedge may not seem ingenious nowadays, but it was a novel idea then. Ironically, among the players on defense for Yale that day was the Bliss brothers. They were the first to execute a “criss-cross” or reverse play in football while playing for Phillips Andover four years earlier.

The concepts behind plays like the Horse’s Neck and the criss-cross became mainstream because their threat forced defensive ends to spread out and stay home, lessening their ability to defend against the wedge and other mass plays. So, even during the height of football’s mass and momentum era, players and coaches recognized the value of disguise and deception, and we have little men on tabletops to thank for some of that.

Football Archaeology is reader-supported. Click here to buy one of my books or otherwise support the site.

Did I forget to mention that? More important things happened in that game than a silly Harvard-Yale final score.

All well and good…but Yale won 6-0.