Today's Tidbit... The Fundamentals of Kicking in 1923

Today, we'll examine Chapter VIII of The Fundamentals of Football, which covers drop kicking and place kicking. It provides several examples of techniques and strategies that made sense under a different set of rules than those that exist today.

Wilson published the volume in 1923 when footballs had more rounded ends than they did after the rule makers resized and reshaped the ball in 1929 and 1934. Drop kicking largely disappeared from football after those changes to the ball.

The Fundamentals of Football was part of the Wilson Athletic Library, which included seven other football volumes and another 30 or 40 volumes covering different sports. Major John L. Griffith, the Big Ten Commissioner, and George "Potsy" Clark, the Kansas football coach, wrote the volume. Griffith is also known for creating the Drake Relays while coaching at Drake.

In 1923, teams often attempted field goals and the point after by drop kick rather than placement kick. Griffith and Clark's coaching points for drop-kicking are not particularly technical. The advice comes down to:

Practice 30 minutes per day, which was easier said than done in the nonspecialist era.

Adjust your stance based on the number of steps you take.

Receive a good snap, so you remain in balance.

Drop the ball from as low a point as possible and kick it as it hits the ground.

Keep your eye on the spot on the ball you want to kick and strike it with your toe, not your instep.

Follow through.

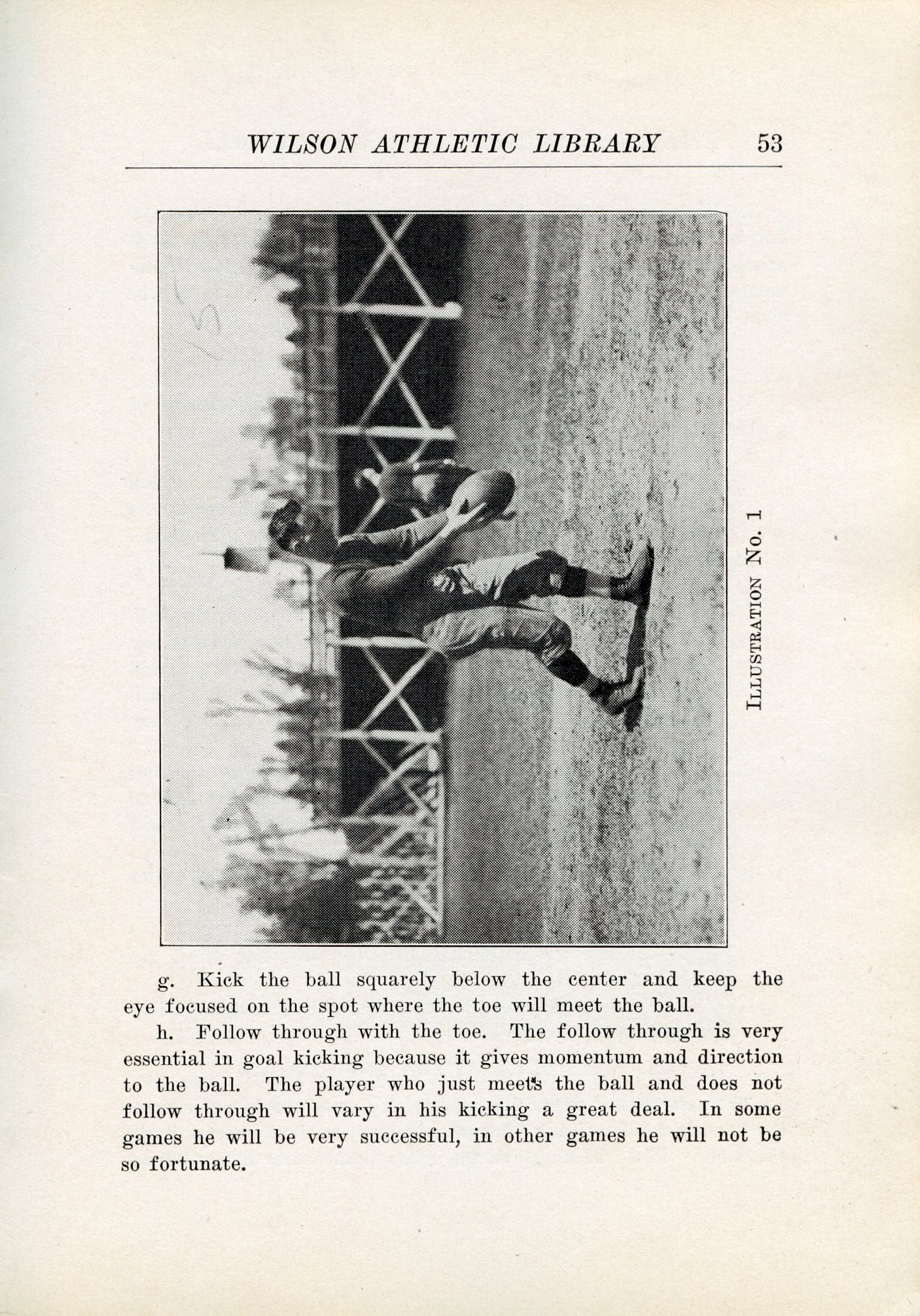

The advice for place-kicking was similarly straightforward.

Mark the placement spot.

Adjust your stance based on the number of steps you take.

Plant your left foot next to the ball and ensure you point it straight ahead.

Keep your eye on the spot where you want to kick the ball and strike it with your toe, not your instep.

Follow through.

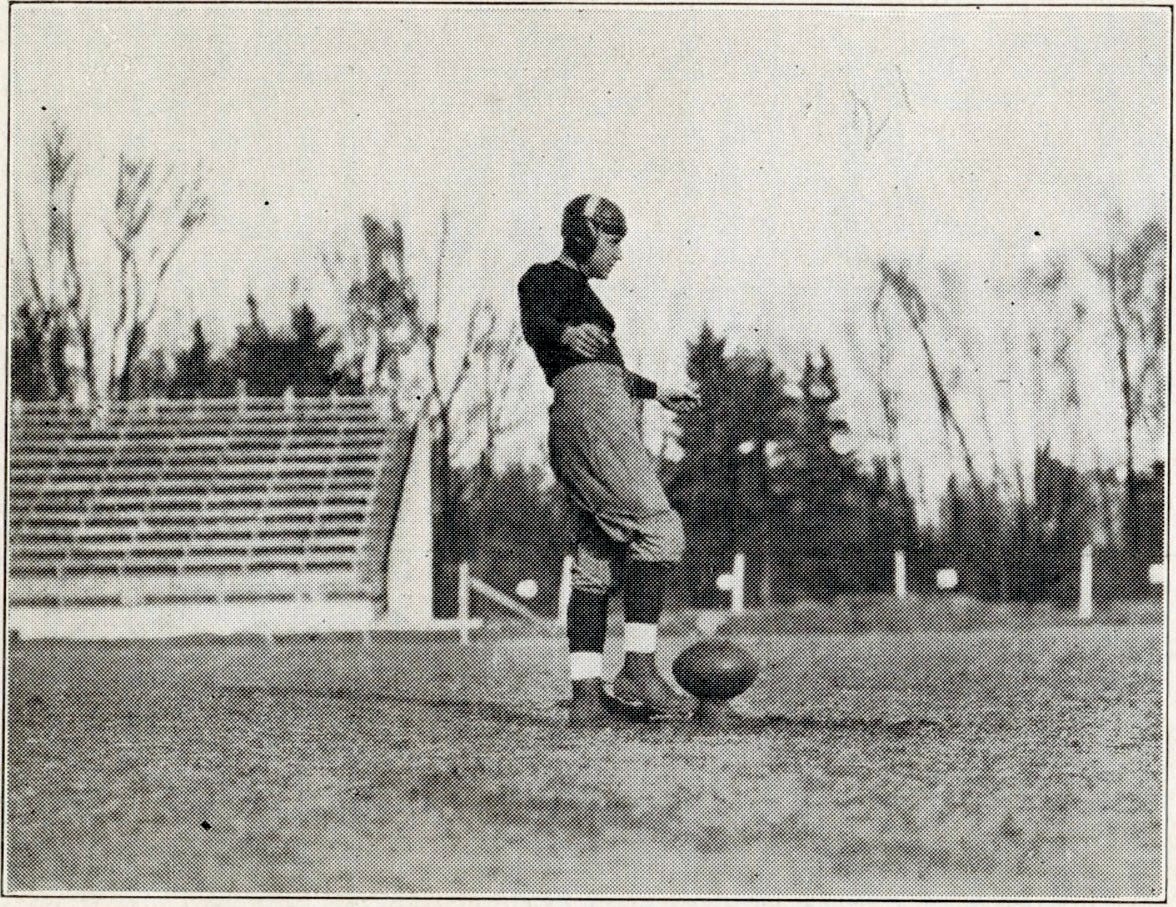

The most interesting coaching points came in their discussion of kickoffs. The rules did not allow artificial tees then, so kickers built the tee by gathering loose dirt on the field or quickly grabbing dirt from a bag they kept on the sideline. (The rules also did not require teams to snap the ball within a designated amount of time, so referees gave kickers reasonable time to build their tees.)

Griffith and Clark describe four approaches for teeing the ball—acute, perpendicular, obtuse, and horizontal—and argue that the horizontal approach is best. Rugby kickers still use the obtuse angle approach on their more rounded ball, but the acute or perpendicular approaches are nearly universal in football today, other than for onside kicks.

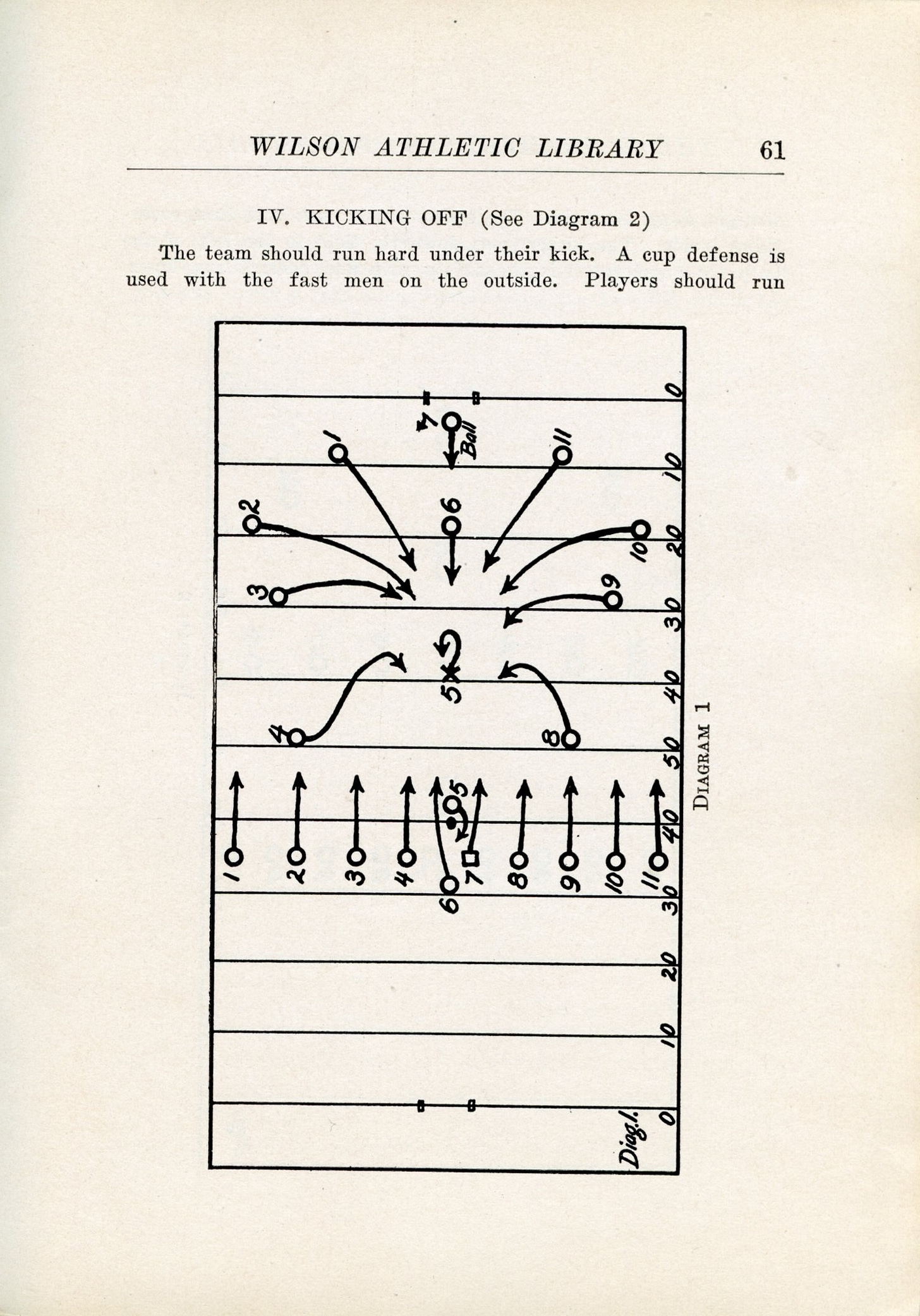

The kickoff technique largely mirrored the placement kick for field goals and extra points, so we will not repeat it. More noteworthy was their recommended receiving team alignment, which had only two players between the receiving team’s 40- and 50-yard lines, a positioning that is illegal today.

Through a series of steps described in Shooting Down the Flying Wedge, the number of players injured due to kickoff return wedges led to rules eliminating interlocked arms in 1910. In 1932, they also required teams to have five players between the 40 and 50-yard lines so the return team would have more difficulty creating a wedge. Other rule changes followed.

We'll cover some additional topics from this series in the future, especially when I get my hands on other volumes in the series.

Football Archaeology is reader-supported. Click here to buy one of my books or otherwise support the site.

I was moved to examine my copy of Leroy Mills' Kicking the American Football (1932), finding attached to the inside front paper a letter from the author to the first owner. Does 'Dick Hyland' ring a bell? ..