Today’s Tidbit... The Oliphant in the Room

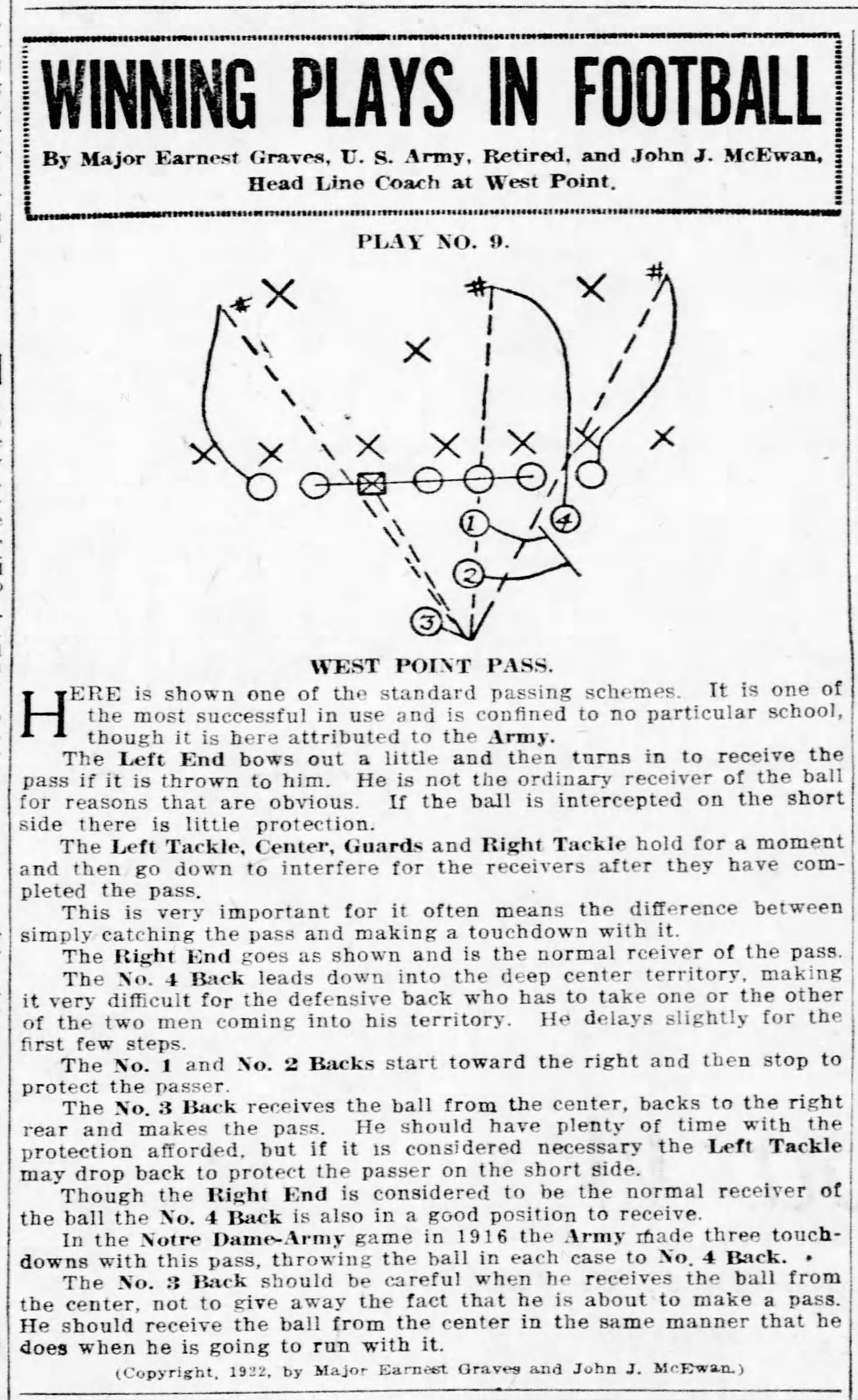

Many football plays depend on misdirection or change of direction, and so does this story. My little journey on this story began when I looked at a play from a syndicated series published by Earnest Graves, a longtime assistant coach at Harvard and West Point, who handled the line at both schools. (We’ll cover the play of interest at the end of this article.)

Notre Dame famously threw the ball over and around Army in 1913 in a game credited with convincing the Eastern establishment to pay attention to the forward pass. The fact that Army turned around and used the forward pass to beat Notre Dame three years later tells us that some Easterners actually paid attention. More important for today’s story is the individual who threw the three forward passes that beat Notre Dame. It turns out it was a fellow Indianan, Elmer Oliphant.

Elmer began his college career at Purdue in 1910, where he earned his numerals as a freshman. Once eligible for varsity competition, he earned nine letters in football, basketball, baseball, and track. In his junior year, he scored five touchdowns and kicked 13 PATs versus Rose Polytech, giving him 43 points on the day, a Purdue single-game record that still stands. He was twice named an All-American in basketball at Purdue before graduating with a mechanical engineering degree in 1914.

Oliphant might have entered the workforce at that point, but instead contacted his congressman seeking an appointment to the Naval Academy. That appointment was no longer available, so Oliphant took the district appointment to West Point instead, entering as a plebe and spending another four years in school.

The academies did not follow the four-year eligibility rules back then, so Oliphant participated in the same sports on the Hudson, earning 11 letters, and becoming the first cadet to letter in all four major sports. He was a two-time All-American running back there. He was so impressive that he was selected in 1958 by the Football Writers Association of America as one of the eleven top players for football’s first 50 years, joining backs Willie Heston (Michigan), Walter Eckersall (Chicago), and Jim Thorpe (Carlisle). Besides scoring 135 points at Purdue and 289 points at West Point, he led the NFL in scoring in 1921.

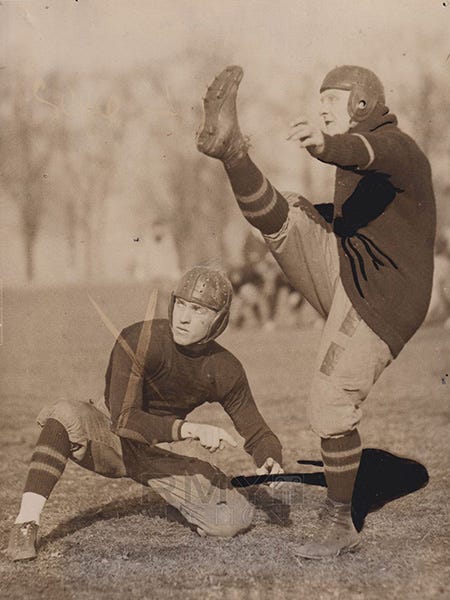

All that takes us back to the 1916 Notre Dame-Army game, which was a tight, low-scoring game in the first half, with Notre Dame leading 10-7 at the break. Army’s Eugene Vidal (author Gore Vidal’s father) dropkicked a 42-yarder early in the third quarter to tie the game, and it was all Army after that. Taking a look at the play mentioned earlier, Oliphant was the #3 back who took the direct snap, while Vidal was the #4 back, aligned as a wing between the right tackle and end.

The play is among the first I’ve found that sent three receivers against a two-deep defensive backfield and had the passer read the defenders’ reactions to determine where to throw the ball. It’s simple stuff today, but the detailed description notes that Army scored three touchdowns on this play versus Notre Dame in 1916, when the forward pass was not yet a teenager.

As it is drawn, Vidal split the seam between the two safeties three times, and Oliphant delivered the ball to him for touchdowns, giving Vidal 21 points on the day and Oliphant 9. (Oliphant added a field goal as well.)

So, Army avenged its 1913 loss to the Irish, Oliphant scored 9 of his 289 points at West Point, and the practice of reading defensive backs to determine where to throw the ball was on the path to becoming a mainstream football strategy.

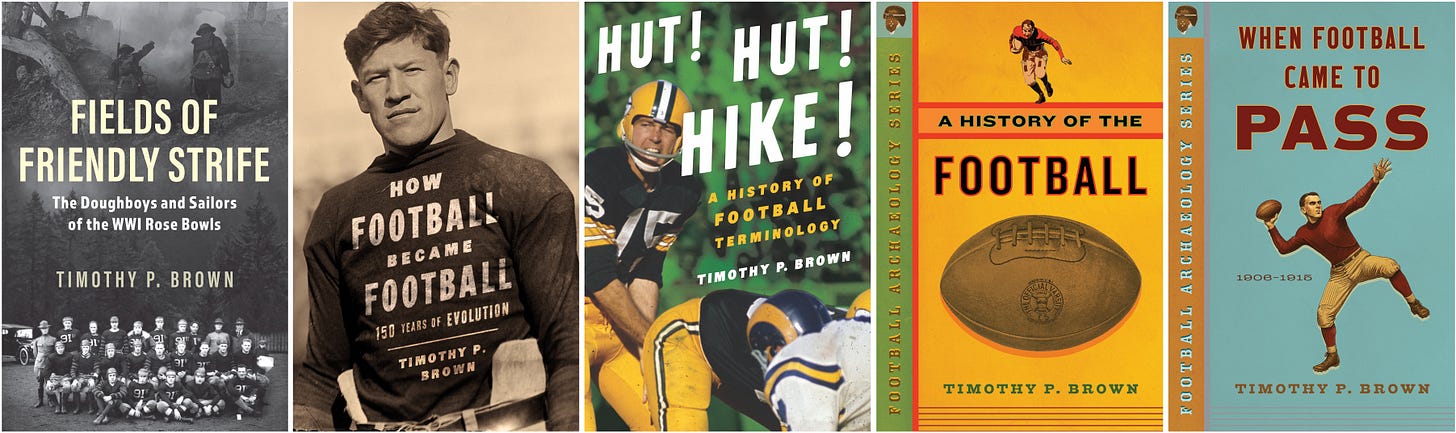

Football Archaeology is reader-supported. Click here to donate a couple of bucks, buy one of my books, or otherwise support the site.

An early grad transfer.