Today's Tidbit... The Origins Of Player Numbers

Sometimes, when you round the corner at a location you have visited many times before, you see something new. A similar feeling occurs when encountering a story that sheds new light on an old topic you’ve researched in the past.

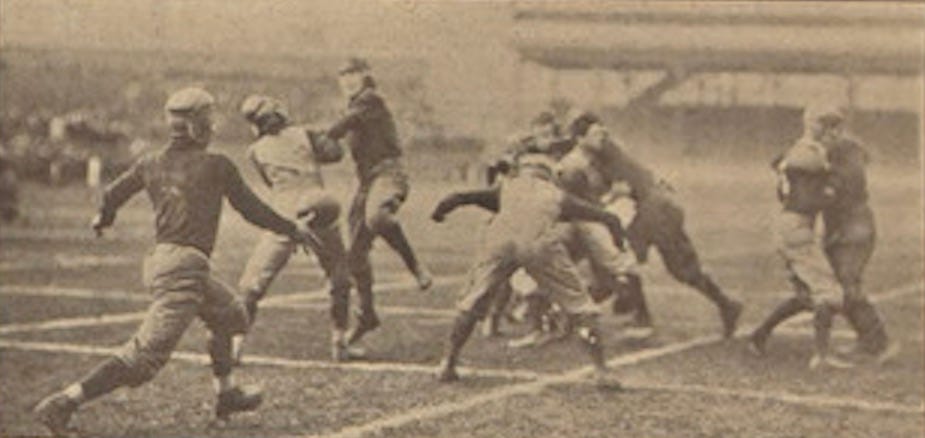

The other day, I found an article about Carlisle's hidden ball trick, when Pop Warner had football-shaped brown patches sewn on the front of Carlisle's uniforms for their 1903 game at Harvard. When Harvard kicked off a Carlisle player retrieved the ball at the team gathered together, stuffed the ball under one player's sweater, and then ran in different directions. Harvard failed to notice Carlisle's Dillon running straight downfield and crossing the goal line with the ball tucked under his sweater. Since Dillon did not have a number on his back, no one knew who scored the touchdown until later, a point noted by a reporter who have previously argued for numbering players.

Since the hidden ball trick came in 1903 and my previous research indicated that Amos Alonzo Stagg was the first to publicly argue for numbering players in 1901, I looked into early numbering again and found a reference from 1894. According to the New York Sun story, the idea of numbering players came from a fan standing along the sideline at that year's Yale-Princeton game played in the rain at Manhattan Field, making it more difficult than usual to tell one player from the other. As the fan noted": “…the average observer finds as much difference in individuals as in a flock of blackbirds.”

The fan's core argument was that most spectators at the big games were unfamiliar with the individual players and needed the players numbered to tell one from the other. Stagg was coaching Chicago by then, so he may not have heard of this fan's suggestion, but the article shows he was not the first to suggest the idea, though he and Camp were the first football insiders to promote numbering players in 1901. Opposition to numbering came from three primary concerns. First, some held that numbering players would promote individual play and glory rather than a team focus. Second, many argued the game was by and for college students, and despite fans paying for their admission, they should not dictate game rules and practices. Third, coaches often opposed numbering because it made it easier for opponents to scout and diagnose formations and plays.

So, the idea of numbering players went nowhere until the Drake-Iowa State game on Thanksgiving Day 1905, which was the first game in which football players wore numbers. As was common until the mid-1910, Drake and Iowa State painted numbers on white canvas patches or shields and attached them to the back of the jerseys. (Kansas considered wearing numbers for the Missouri game the same day, but I could not find evidence they did so.)

Reports indicate that Wichita State wore numbers versus Drury in 1908, and Pitt reportedly wore them during the 1907 season. Still, the first photographic evidence besides the 1905 Drake-Iowa State game comes from Pitt's 1908 season when they appear to have worn numbers throughout the season. Most images show they (and some opponents) wore the canvas patches, but news reports and the first image show a player wearing a number stitched on the back.

In 1909, reports indicate numbers were worn for Michigan @ Marquette, Cincinnati @ Tulane, and all of Pitt's games, so Pitt pioneered the regular use of numbers but did not originate player numbering as they claim.

Numbering grew in use in the 1910s but did not become an NCAA requirement until 1937, when numbers on the front and back of jerseys became mandatory. There were a few bumps along the way with teams using four-digit numbers, Roman numerals, and alpha-numeric combinations. Still, football eventually settled into the system of numbering players by position groups that continues in use today.

Football Archaeology is reader-supported. Click here to buy one of my books or otherwise support the site.