Today's Tidbit... The Tie Goes To The Kicker

Before free substitution, expanded rosters, and specialization, the game had football players who kicked rather than kickers who played football. Kickers were Swiss Army knives who did two or more things well rather than one.

Kickers did not practice their craft as often or as intensely as their other jobs, and the percentage of field goals and extra points made suffered as a result. Nearly every kicker used the conventional or straight-ahead approach rather than the sidewinding soccer style, meaning they kicked with their toes.

Using tricks for better kicks, they added square toes to their shoes and laid tape measure-like devices on the ground to improve their aim. The NFL banned both, while the NCAA maintained the freedom of toe choice.

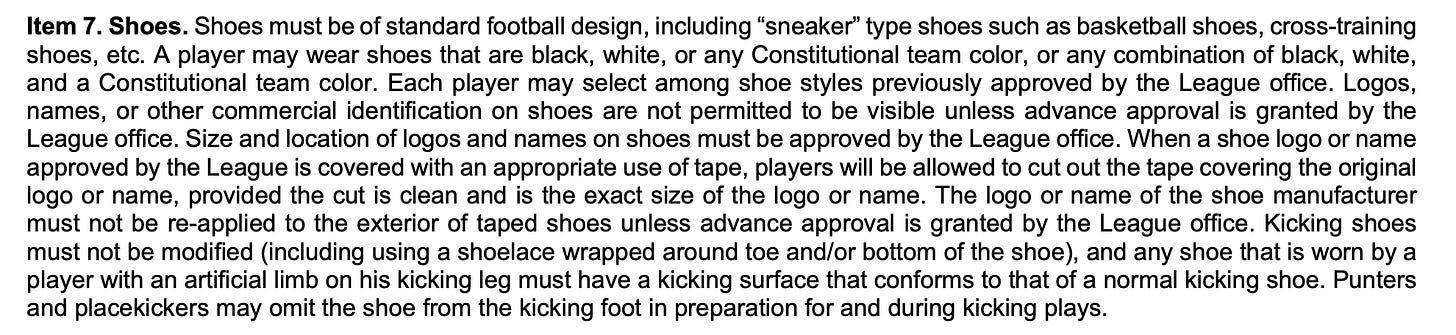

Yet another kicking innovation emerged in the late 1950s when kickers started tying up their toes with their shoelaces. The first kicker known to tie one on was Don Caraway, a fullback at Houston who doubled as a kicker. After playing for Calgary in 1957, he was in the New York Giants camp in 1958 when his unique approach to kicking appeared in newspapers nationwide. The Giants cut him anyway, leading to him spending that season and three more playing in Canada, where he booted or toed three extra points and one field goal.

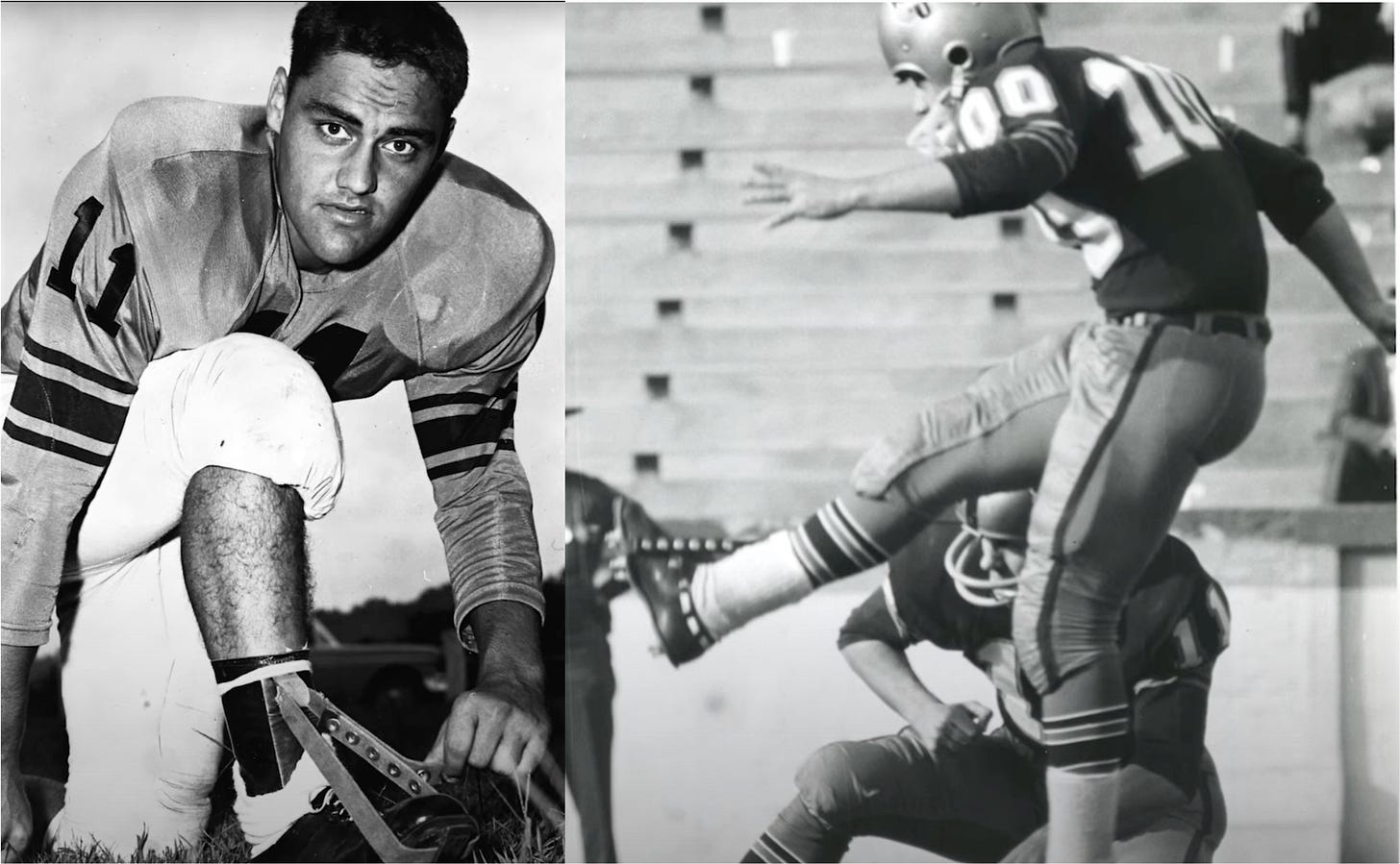

Joe Kuharich toured NFL training camps in 1963 to advise on rules and technical issues when he encountered Vanderbilt rookie Grady Wade in the Colts camp. Wade had an attachment on the toe of his kicking shoe through which he looped a shoelace around his lower shin. Wade used the device in high school and at Vandy, but Kuharich declared it against the rules. As it turned out, Wade did not make the team, but Kuharich's ruling was overruled, and a handful of kickers continued turning up their toes.

Tying up the toe grew in popularity among high school and college kickers, but the NFL outlawed the shoelace approach in 1969. The ban remains in place today and extends to all kicking shoe modifications.

However, tying up the toes remained okay in the college ranks. Some kickers moved beyond shoestrings and used purpose-built devices to lift their toes. Chuck Kinder, who kicked for West Virginia, wore a fancy device. He also wore the number 100 during the 1963 season to celebrate his state's 100th anniversary.

Jay W. Sheppard took the next step by filing for and receiving a patent for a toe-lifting device in 1977.

Of course, by the time Sheppard gained his patent, America had been invaded by immigrants whose longer and more accurate soccer-style kick led to the loss of jobs among American-born conventional kickers. The insidious invasion even led to red-blooded American boys using the sidewinding approach, and by the mid-1980s, conventional kickers were as rare as hens' teeth.

With conventional kickers disappearing due to natural causes, the NCAA never banned the turned-up-toe approach, its devices, or even square-toed shoes. As far as I can tell, all remain legal under the 2024 NCAA rules.

For others stories about kicking aids:

Click here for options on how to support this site beyond a free subscription.