Today's Tidbit... Triple Laterals and the Dead Ball Era

Yesterday's Sunday Night Football game saw the Buffalo Bills dismantle the San Francisco 49ers 35-10 on a snowy field, with one touchdown coming on a spur-of-the-moment lateral by wide receiver Amari Cooper to quarterback Josh Allen. After taking the snap at the 7-yard line, Allen completed a pass to Cooper short of the goal line. As the 49ers' defenders pushed Cooper backward, he threw caution to the snow and lateraled to Josh Allen, who ran to Cooper's left before diving and extending the ball across the goal line for a touchdown.

The Bills did not script the lateral. Few teams have downfield laterals or hook-and-laterals on their play cards today, but those plays abounded in 1935 due to a rule change or two.

Throughout the game's history, debate has raged over whether defensive players should be allowed to advance recovered fumbles. Rugby’s rules allowed anyone to pick up and run with the ball, but defenses advancing fumbles came to be seen as profiting from chance, so the rule makers of 1929 declared the ball dead when the defense recovered a fumble. (Fumbles recovered in the air, and interceptions remained live.) The 1929 rule reduced the riskiness of lateraling in space, so laterals previously used only in extreme circumstances became more common.

Despite the change, football teams struggled to score in the 1930s, so there was a desire to encourage more laterals. The 1935 committee instructed officials to employ a "slow whistle" when a defender stopped an offensive player's progress but did not take him to the ground. This emphasis allowed more downfield laterals, including more than one per play.

So, what happened during the 1935 season? The triple hook and lateral pass happened. The game was awash with them, relative to their past use. Offenses of the 1930s emphasized backfield misdirection plays in the Single and Double Wings, Notre Dame Box, tandem, and other formations. Teams spent inordinate amounts of time on spinners and other precise backfield movements to disguise where the ball was going. Those plays took extra time to develop, making the pace change coming from the quick-hitting Modern T and Split-T offenses of the 1940s more effective.

The focus on precise backfield movements transferred to the passing game. The hook-and-lateral pass, which had been around since Bob Zuppke created it in 1910, benefitted from the "slow whistle."

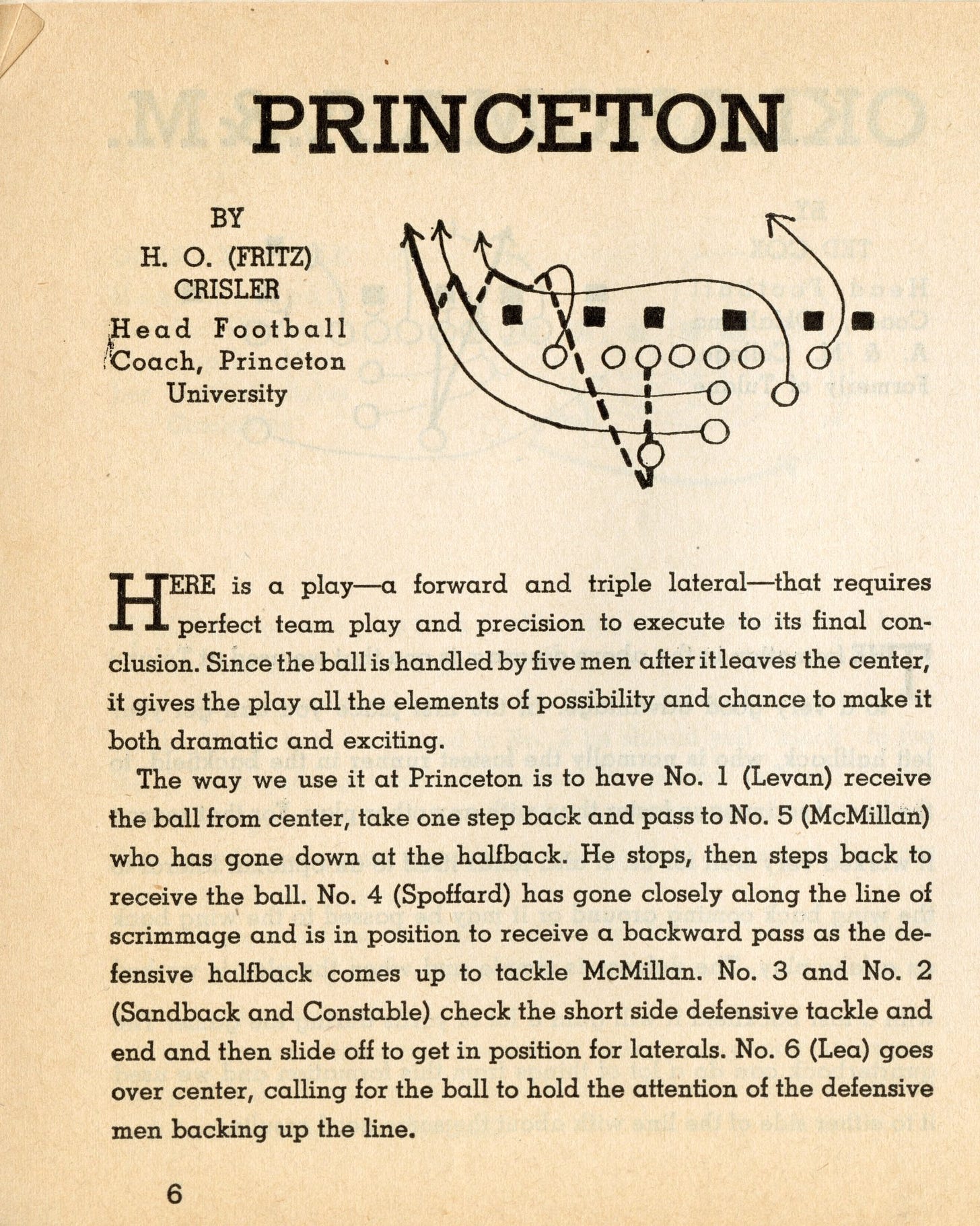

The diagram below shows the triple hook-and-lateral pass employed by Fritz Crisler's Princeton team. It took advantage of the fact that a defender might stop the pass receiver, but the slow whistle gave him time to toss the ball to a teammate sweeping by.

The play required precise timing and the avoidance of backers-up (aka linebackers) who might get in the way. Despite the play's complexities, Don Faurot used it in Missouri, Furman and The Citadel became proponents, and Mississippi State's use of double and trip lateral passes was an indicator of their playing "modern football."

Ohio State used the play against Michigan on their way to a 28-0 shellacking of the Wolverines, the highest score differential in the series to that point. Likewise, Georgia Tech used the play against Florida but went to the well one too many times and had the pass or lateral intercepted.

Although the triple lateral pass had its day or years in the sun, the development of the Modern T's dropback passing game led to darker days for such precision and trickery. Spacing and timing, rather than trickery, became the focus of passing offenses.

The restriction on college defenders advancing fumbles remained in place until 1990. Defenders were also allowed to advance fumbled backward passes for the first time in 1998.

Football Archaeology is a reader-supported site. Click here for options on how to support this site beyond a free subscription.

Too many commentators have forgotten about the hook and ladder play, thinking it’s a misstatement of hook and lateral.