Today's Tidbit... When Football Was A Game Of Millimeters

Since 1912, American football has been played on a field 100 yards long and 160 feet (53 1/3 yards) wide, but in the 1970s, there was a movement to encourage the U.S. to shift to the metric system, culminated by the Metric Conversion Act of 1975. The Act encouraged federal agencies and others to voluntarily switch to the metric system. The movement and the Act had some success, but the American public proved uninterested or unwilling to give an inch in most situations. Today, we need two sets of wrenches and buy Coke in 12-ounce cans and 2-liter bottles, yet the meter as a metric has a limited presence in everyday life.

In the sporting world, Americans once ran on 440-yard tracks and swam in 25-yard pools, while the rest of the world used the metric system, so we converted to their system so we could compare our times. Other countries borrowed baseball and basketball from us, so the bases remain 90 feet apart, and the basket still stands ten feet above the court. Besides Canada, which had its version of football, no one else played American football, so there was little pressure to convert to a metric gridiron.

Neither the NFL nor the NCAA showed any inclination to convert football to a metric game. Yet, some folks, including University of New Orleans chemistry professor Ralph D. Kern, could not leave well enough alone. He argued in 1974 that football's focus on moving the ball in 10-(insert measure of length) increments created an opportunity to educate the public on the beauty and logic of the metric system if only the game underwent a conversion. Kern advocated using a field 100 meters long (about nine yards longer than standard) and 50 meters wide (about two yards wider), with teams gaining ten meters (about eleven yards) for a first down. The coverage of Kern's proposal did not mention the height and width of the goal posts or the size of the ball, so they would presumably be unchanged.

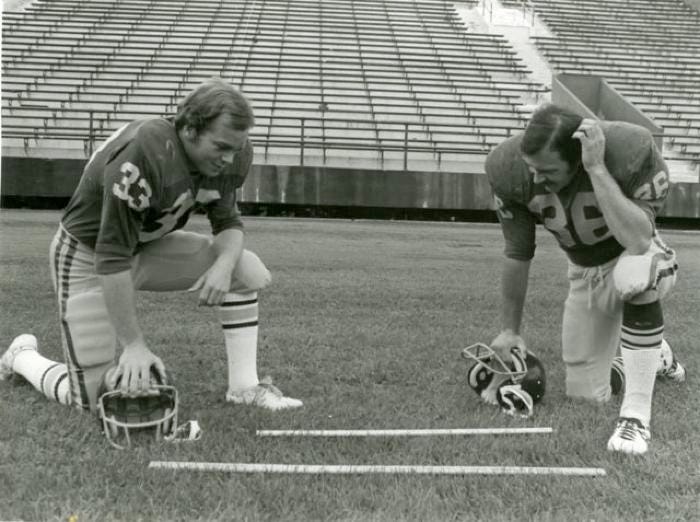

It turns out that Kern was an idea man, not a man of action. Still, Northfield, Minnesota, had an action figure in the form of Carleton College chemistry professor Jerry Mohrig who convinced the powers that be to play the Meter Bowl or Liter Bowl, depending on the nickname you prefer. Carleton joined their crosstown rival, St. Olaf College, in playing their 1977 non-conference rivalry game on a field without yard lines. Instead, it had meter lines. A key requirement of gaining NCAA approval to play the game was the agreement to convert the game statistics from meters back to yards before submitting them to the bureau. (How the NCAA would have treated a record-breaking 100+ meter pick-6 is unknown.)

The game attracted 10,000 curious fans and received coverage in newspapers and major television networks nationwide, with highlights shown during the day's national game of the week. Of course, while the marketing folks had fun promoting the game, the grounds crew had actual work to do. While the field proportions remained normal, everything had to be metered, requiring the relocation of every sideline, yard line, goal line, end line, and Lockney Line. Likewise, the goal posts shifted 4 1/2 feet from their usual spots, and the chains gained a few links.

The play on the field was essentially unchanged and uneventful. Sure, there were plays in which the offense failed to earn a first down after gaining ten yards, but that applied to both sides. In the end, it was not a game of inches. Carleton gained 0 meters rushing and 106 meters passing. Meanwhile, St. Olaf gained 302 meters on the ground and 91 meters through the air on their way to a 43-0 victory.

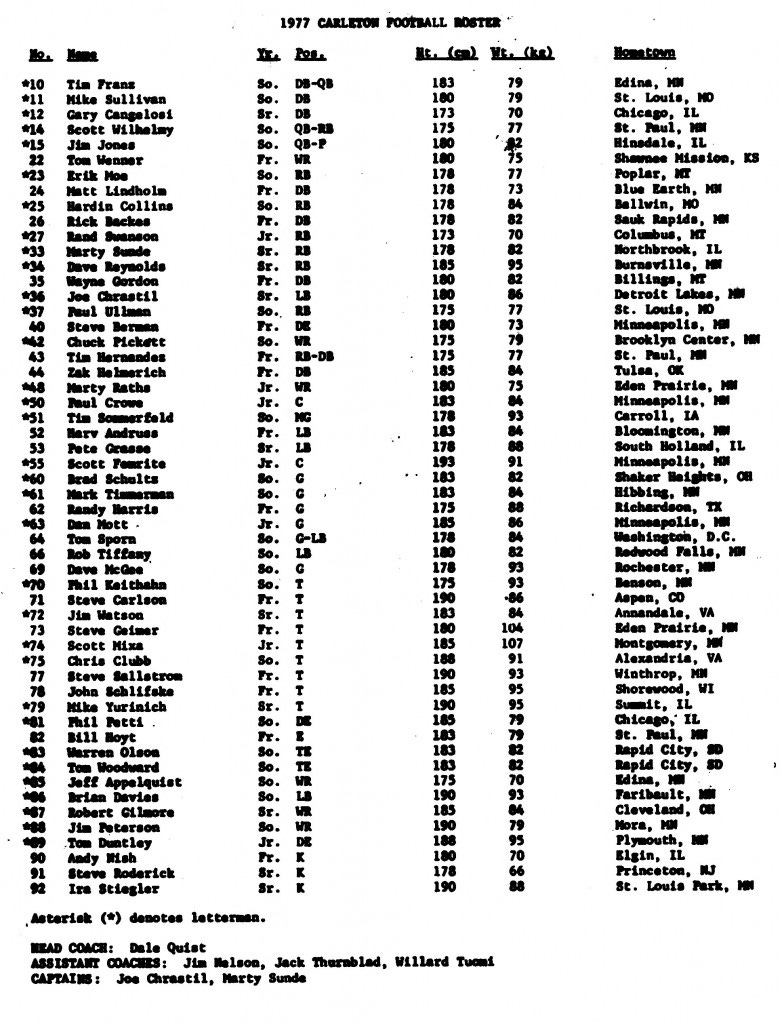

Much of the uniqueness of the game occurred off the field. For instance, the game program listed the players' heights in centimeters and their weights in kilograms.

The student bodies, which normally ignored their DIII classmates, attended in droves, many wearing T-shirts celebrating the game or holding appropriately-themed signs. Carleton, which did not have a cheerleading squad, had students volunteer to be cheer-liters for the day.

By any standard, the citizens of Northfield had a fun day watching the only known football game played on a metric field. Unfortunately for them, the game did not start a trend; it was an aberration as the rest of the football world continued playing the 2.7 meters and a cloud of dust style that dominated the 1970s.

Click here for options on how to support this site beyond a free subscription.