Today's Tidbit... When Students Built Football Stadiums

College athletic teams began as student-run organizations. Athletes initially trained themselves and then formed athletic associations to handle the finances and hire coaches. Athletic administration then transitioned to faculties, alums, graduate student managers, and, finally, professionals.

Those transitions did not occur evenly across the nation. While alumni donations allowed the administrators at Harvard and Syracuse to open massive concrete stadiums in 1903 and 1907, many schools nationwide had primitive facilities that were improved not by hiring a contractor but by students raising funds and providing the labor during the renovation and expansion process. Though it is hard to imagine today, students at the Universities of Missouri and Texas did just that in 1907.

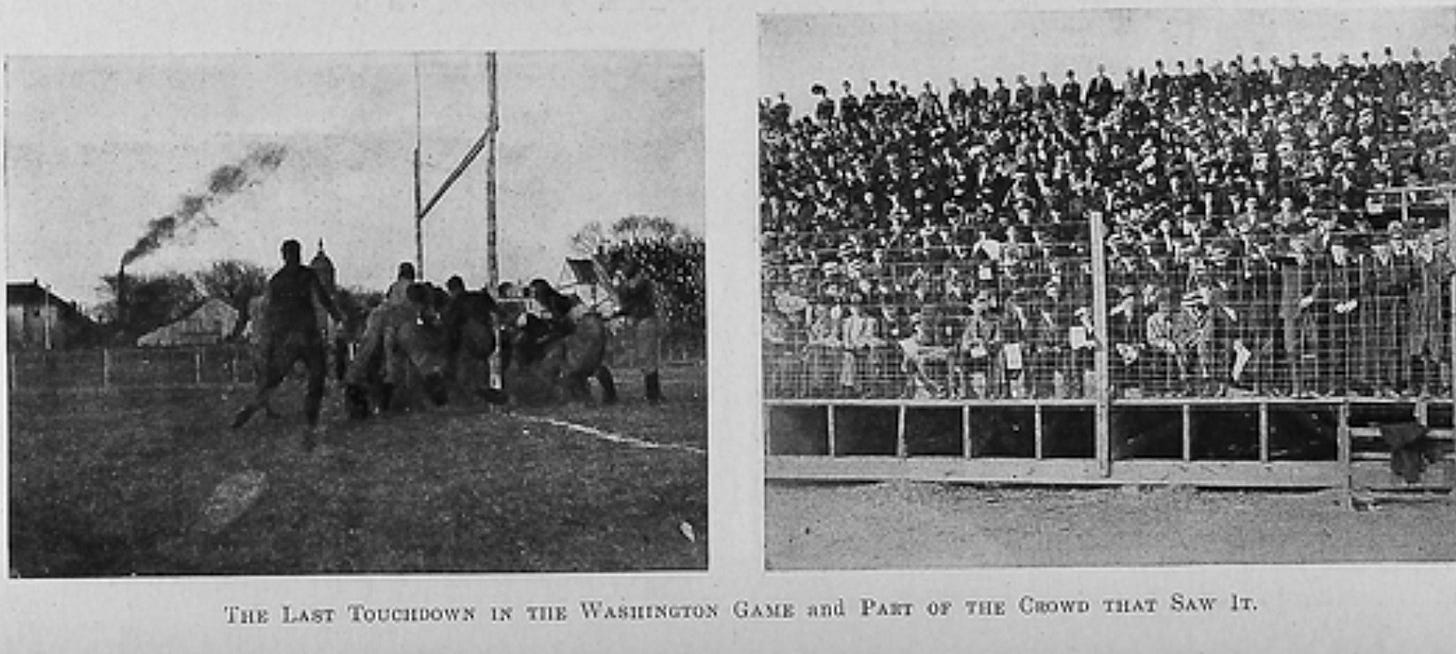

Missouri entered the 1907 season playing at Rollins Field, which was little more than an open field with seating for 1,500. Big games attracted more people than the available seats, so Mizzou fans and visitors sat in carriages and wagons or stood several deep around the field.

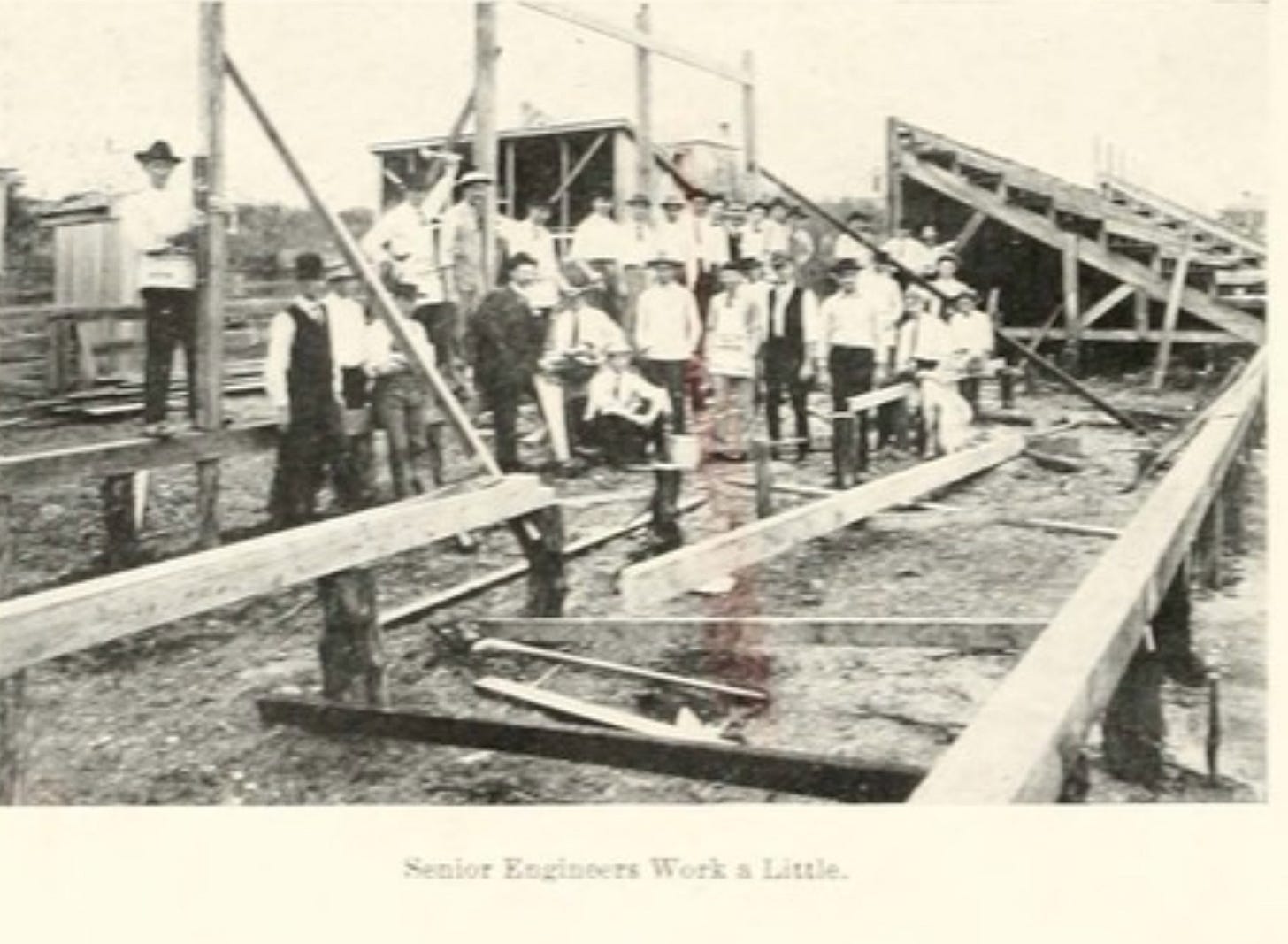

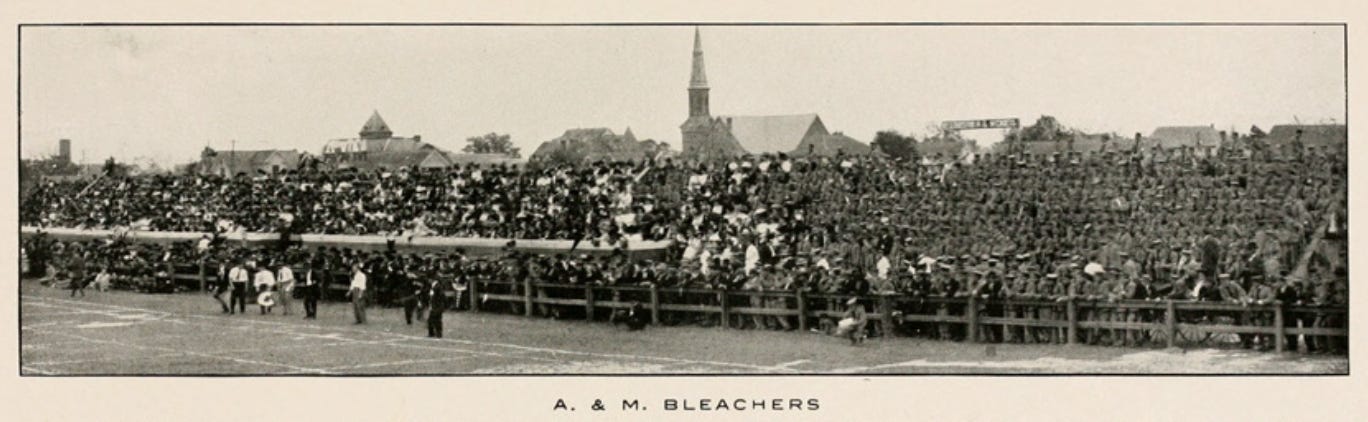

Desiring an improved stadium for the upcoming games with Texas and WashU, the student body organized itself and created a plan to double Rollins Field’s capacity. Working with Dean Waters of the Agriculture Department, the students identified 70 white oaks in a nearby state forest, felled them, hauled the timber out with teams of horses, and used the wood for posts and planks. The students also quarried rocks for the bleacher foundations. The students then used those materials to build an expanded set of bleachers at Rollins Field.

Before, during, and after the building process, other students raised $1,100 for various expenses by selling silk ribbons reading "Bleachers '07" for 50 cents apiece. At the same time, the campus women fed their male counterparts as they labored on the work crews. The students completed the project in time for the Texas game, a 5-4 victory for the Tigers. Despite losing, the Texas fans and team were left Columbia impressed by the expanded stadium and the process the students used to fund and perform the work.

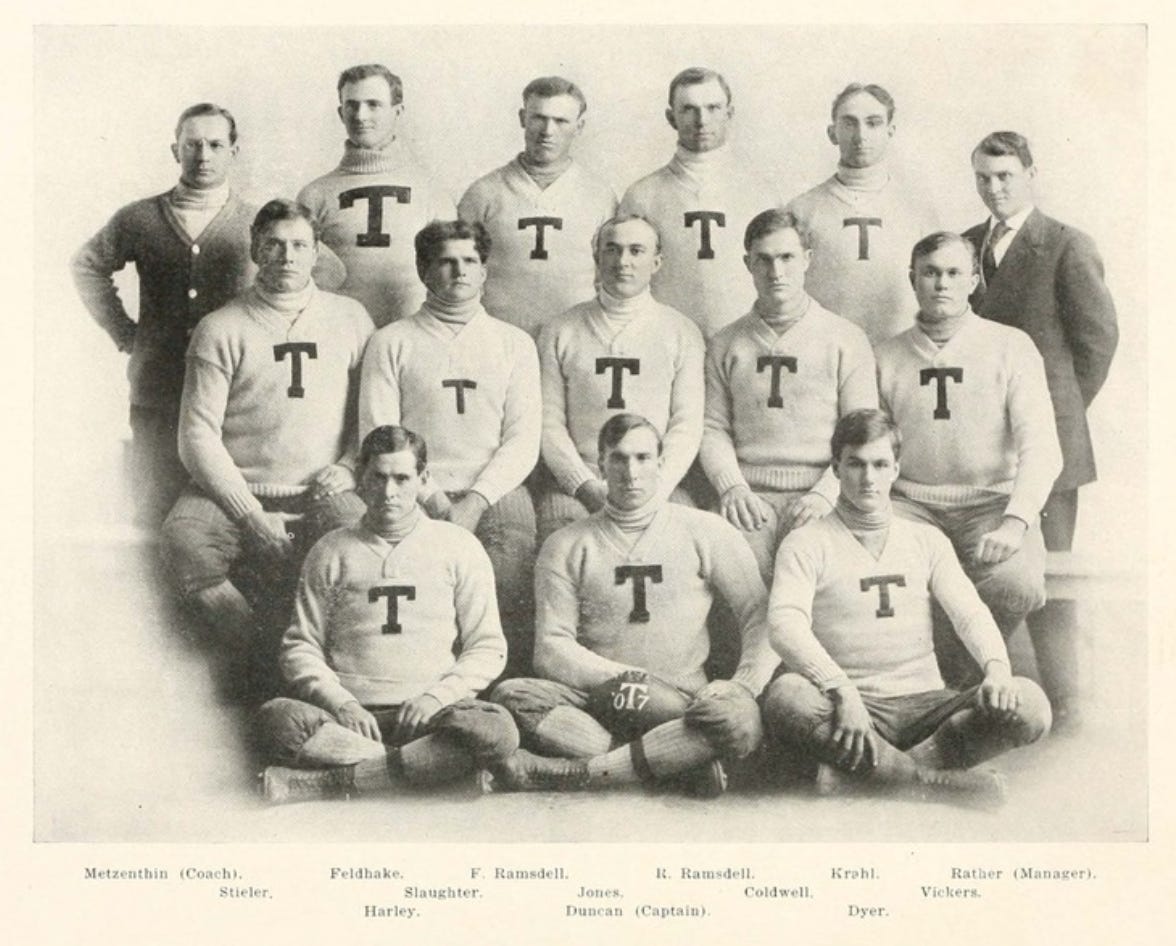

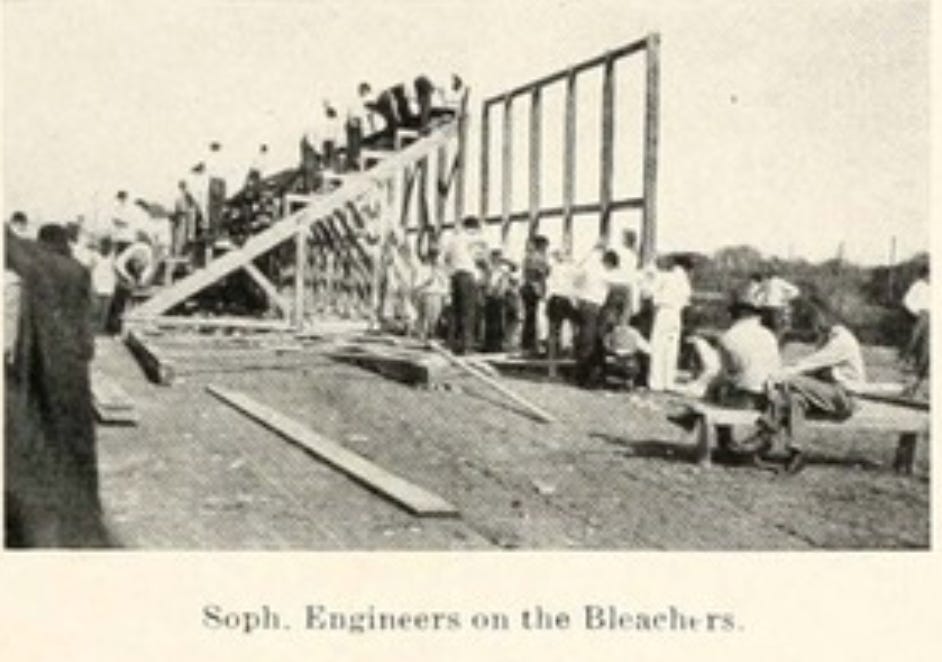

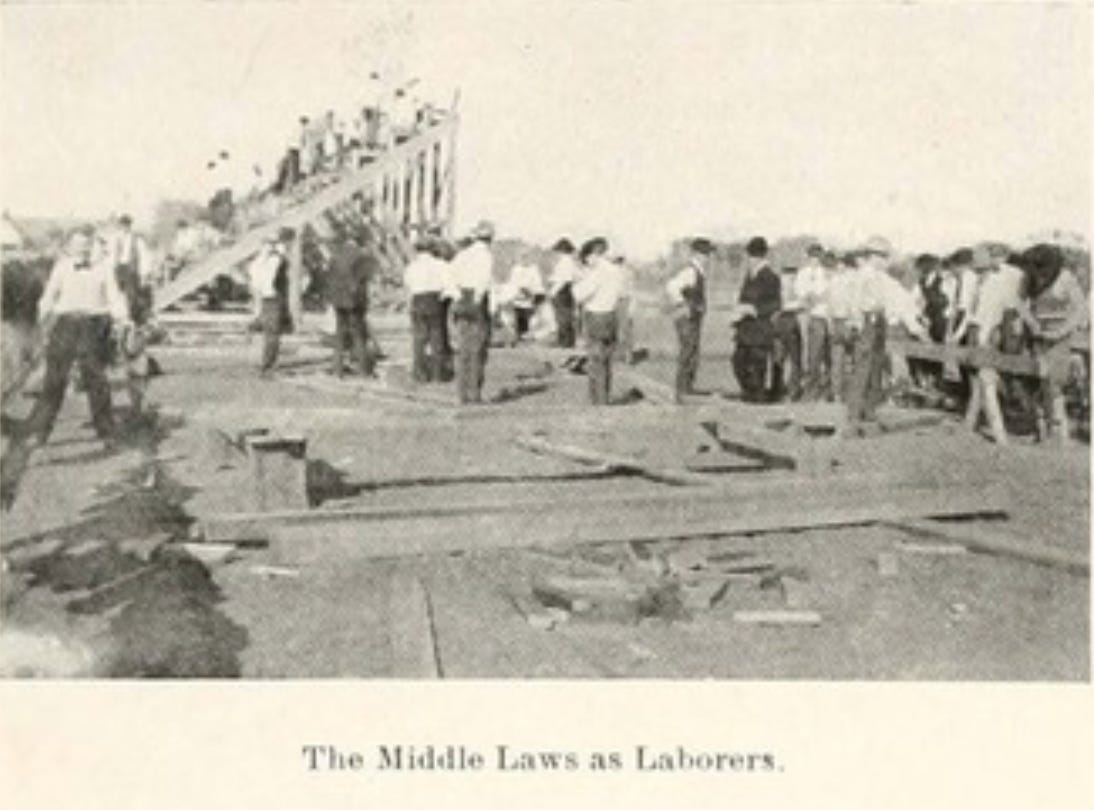

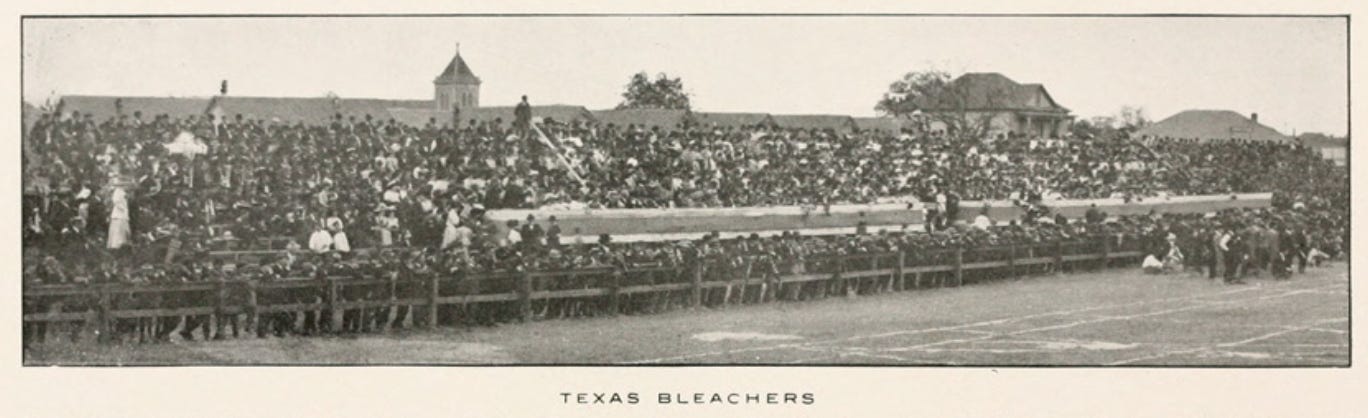

When the Texas team returned to Austin during the first week of November, the student body learned what their Missouri counterparts had achieved and quickly began planning for the same. They held an all-campus meeting on November 11 to discuss and gain approval of plans to double the capacity of 1,500-seat Clark Field in time for their November 28 rematch with Texas A&M.

Like Missouri, the Texas students sold badges with "T. Bleachers" printed on them. Priced at 50 cents apiece, students and faculty bought 662 of them. In addition, a group of campus women created a banner bearing a Texas T and a football and auctioned it for $325 at a pep rally the night before the Oklahoma game. Combined with other donations, the students raised the funds needed to buy the lumber, nails, and other supplies and set to work.

The project leaders organized work crews by class and discipline (Engineering, Law, and Arts & Sciences), while the faculty allowed students to skip classes on their designated workdays. The crews built the bleachers in movable sections to allow their reconfiguration for baseball, and they completed their work a day or two before their 11-6 Thanksgiving Day win over A&M.

The Longhorn students repeated the process on a smaller scale in 1908 when they erected additional sections adding 400 seats on the visitor's side of the field, which still did not meet the ticket demand. Texas added seats periodically until the concrete Alumni Stadium came along in 1924.

There were other instances of students building or expanding football stadiums in the days when wooden bleachers were the norm. Still, the DIY approach saw less use as concrete, brick, and steel became the standard building material for stadiums, and athletic facilities fell under the control of campus administrators.

Football Archaeology is reader-supported. Click here to buy one of my books or otherwise support the site.