Today's Tidbit... "Wild Animal" Mascots

I've written before about the arrival of mascots among football teams. Mascots started as team member pets, children, or neighborhood kids, and they became known as mascots after the popular 1880s opera La Mascotte.

However, one of my brothers considers live mascots interesting, so I thought I'd look into "live mascots" before 1920 to see what I would find. However, I narrowed the scope to wild animals used as live mascots.

I do not consider dogs, ducks, goats, or mules worthy of my research and scholarship time. Neither did I consider domesticated or nearly domesticated animals, like longhorns, buffaloes, and birds of prey, to be wild animals. I would think about it differently if Colorado picked a random buffalo off the range on Friday and paraded it on the football field the next day, but they don't, so I won't treat their trained beast as a wild animal.

Some schools acquired wild animal mascots, and some had animals unrelated to their official mascot then or now. Cal acquired an Alaskan bear in 1895, shortly after adopting the bear mascot. A Princetonian brought a tiger to a 1902 game. Other schools contributed to the menagerie with a badger, a bobcat, a wildcat, and a few eagles. Most came through friends of a friend looking to offload their beast on others. You could acquire a used badger for $25 in 1905, and one or two schools established bounties for the first trapper to bring in the target animal.

In the dozen cases found, the wild animals only stayed briefly. One reason relates to my vague childhood memories of visiting the Milwaukee County Zoo in Washington Park. A new Zoo was then under construction to replace the 1892 zoo, which displayed animals in concrete, stone, and iron-barred cages. While the zoo animals had little room to exercise or entertain themselves, the wild animals used as mascots likely fared worse.

Even pre-WWI, many thought we should not keep wild animals in tiny cages so they could serve as carnival props at football games. It was against the natural order of things.

In addition, keeping wild animal mascots on a college campus took a lot of work and was expensive. At one school, football team members contributed ten cents per week to feed their mascot, a hog, but there was only so much enthusiasm for that expense despite the hog serving another purpose once fattened. LSU's Mike the Tiger is the only wild animal mascot I can think of, and he did not arrive until 1936, well after my search period.

So, except for dogs, goats, and other domesticates, pre-WWII mascots primarily existed on paper. They weren't seen online, on television, or even heard on the radio until the late 1920s. Mascots existed in fans' minds and were cartoon figures in newspapers, magazines, yearbooks, parade floats, and campus artwork. No one marketed the mascot. The campus bookstore did not have shirts and hats emblazoned with the little tyke. Mascots were accepted as articles of faith, lacking a corporeal existence.

That changed in spots in the 1920s and 1930s when a few zany kids dressed in costume on a college football weekend. Their zaniness went viral, though it was the slow-developing kind of viral. Additional costumed mascots arrived at the end of the 1940s and then steadily built until a tidal wave of mascots smothered everything. Few among us are mascotless these days.

Assorted wild animal mascot factoids and images worth sharing:

California Senator Eli Denison sent a live California eagle to Mayor William McKinley in 1896 to show support for Big Mac's presidential bid. While not sports-related, the story has a great cartoon.

Michigan hosted Minnesota in 1902, the year before the first Little Brown Jug game. Someone painted a wild turkey blue and yellow to celebrate and released it on the field during the game. Soon recaptured, it made a fine meal at a local fraternity house.

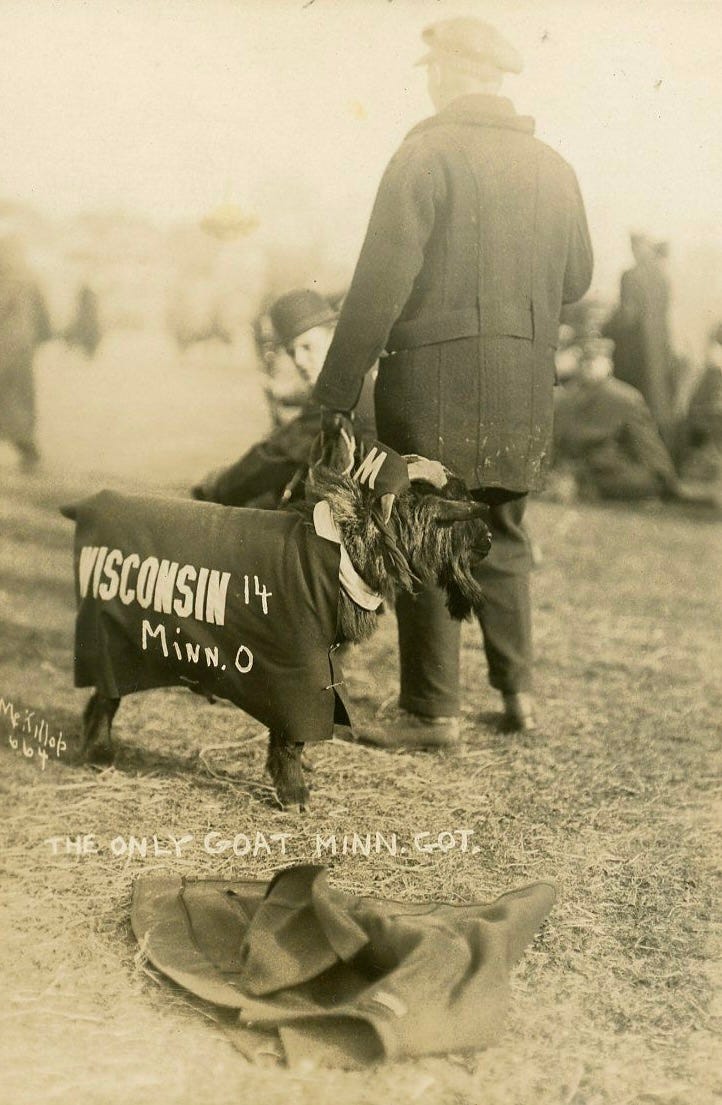

In cases of mistaken identity, Army used a bear as a mascot when facing Navy in 1907, and Wisconsin kicked Minnesota's goat in 1912.

Cornell had a bear named Touchdown shipped in from Maine in 1915. The reports indicated the bear stayed in Haddon Hall, the same spot as the football team and coaches. The bear also joined them for the training table.

We'll end our tale with a bear named Joe College that showed up at Baylor a few decades later. As seen in the image at the top of the story, he was frisky enough to chase the 1940 football team around the field and friendly enough to accept a Dr. Pepper from a campus coed. If the latter incident is why those inane Dr. Pepper commercials invade my college football afternoon, I hope Baylor never wins another game.

Postscript

Readers have brought to my attention additional teams with live animals—mostly bears and bear cubs—and at least one stuck around for a while. Brown had a live bear mascot in 1906, and his successors often traveled to games, as shown below.

Click here for options on how to support this site beyond a free subscription.

x

I had not, but I Googled him and liked the story. He also showed up after my 1919 cutoff date so I did not come across him.

Iowa had a bear cub "Burch" in 1908 and 1909. It appears in the team photos. Lived in a cage under the stadium. Went to road games also. It grew up and was hard to handle. In March 1910, it escaped and fell through the ice on the river. Newspapers said the body was given to UI's museum, who kept the head, but the museum has no record of it.