Today's Tidbit... WSUI And Football's Early Radio Coverage

Part of the fun of researching football's history comes from trying to understand how football fits within broader social and technological changes, particularly the media. You cannot understand football over the years without recognizing its symbiotic relationship with newspapers, radio, television, the internet, and the monies that came with each advance.

One way to examine those relationships is through documents that show the interplay at some time. Period documents are like insects trapped in drops of amber in that they do not change over time. One example of documental amber is the following brochure from 1925 or 1926, published by radio station WSUI.

Early radio stations had call signs that began with the letter W or K, depending on the station's location. Today, stations west of the Mississippi receive call signs beginning with K. However, the border separating K and W stations fell farther West in radio's early days, when WSUI, operated by the Engineering Department at the State University of Iowa, received its name.

The school now goes by the University of Iowa. Still, early radio was considered advanced technology, so early stations arose from universities and hi-tech firms. The universities used the stations to serve the public good by extending their educational outreach, not to make money, which is where commercial radio focussed a few years down the road when easy-to-use radios with vacuum tubes hit the market.

Now imagine the programming you might be available from Iowa's Engineering Department in 1925. Professional radio occupations such as announcers, DJs, and producers did not exist, so the primary person filling those roles, including the announcing, was Carl Mezner, a radio engineer who became the voice of WSUI by default.

WSUI went online in an era when people received the news from newspapers, and distance learning was correspondence courses that sent material by mail. Radio allowed the university to report the news, offer classes, and inspire or entertain the public over the airwaves. Some of the entertainment offered by WSUI included football.

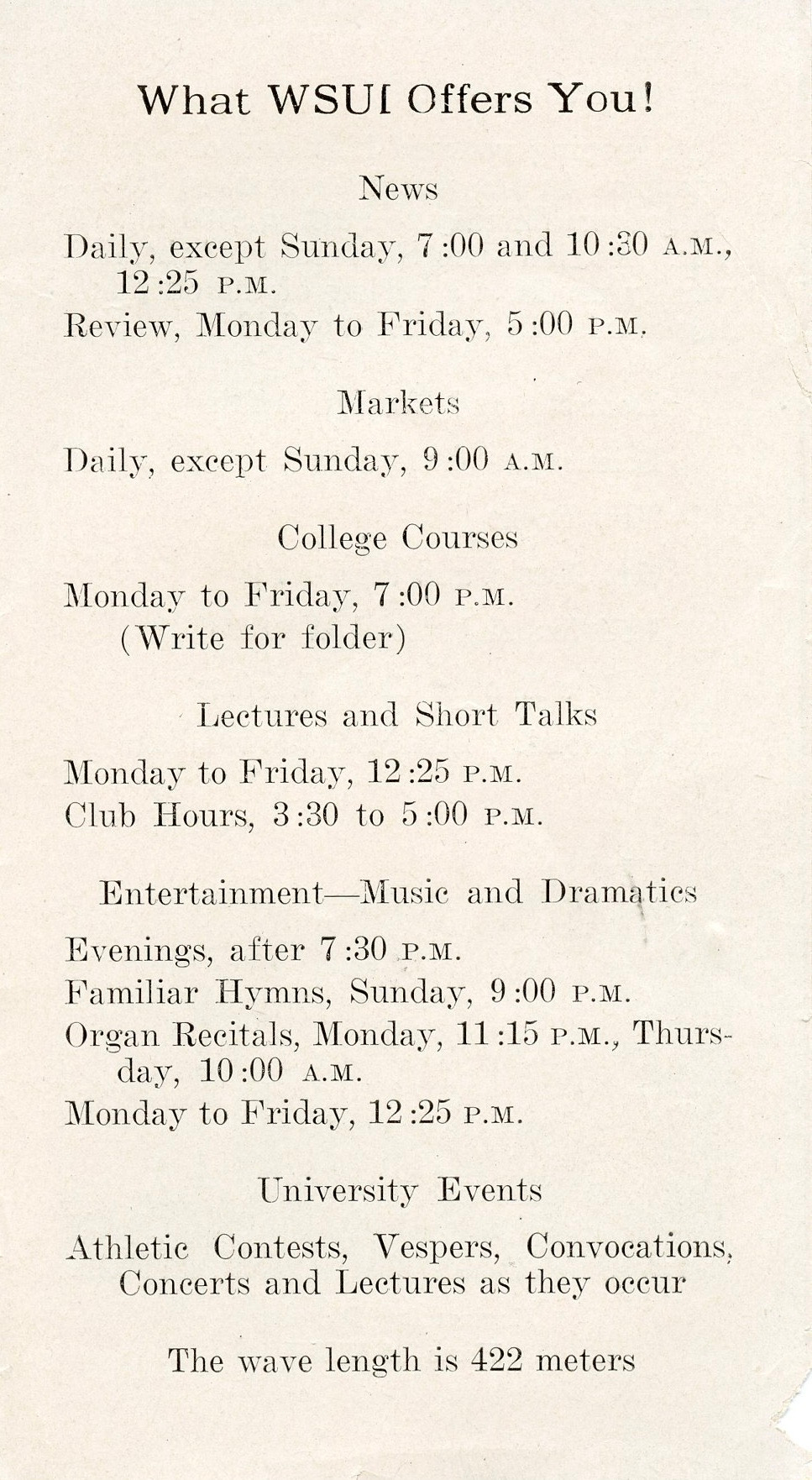

The programming noted in the WSUI pamphlet matches those mentioned in newspaper articles in 1925 and 1926, so the pamphlet is from one year or another.

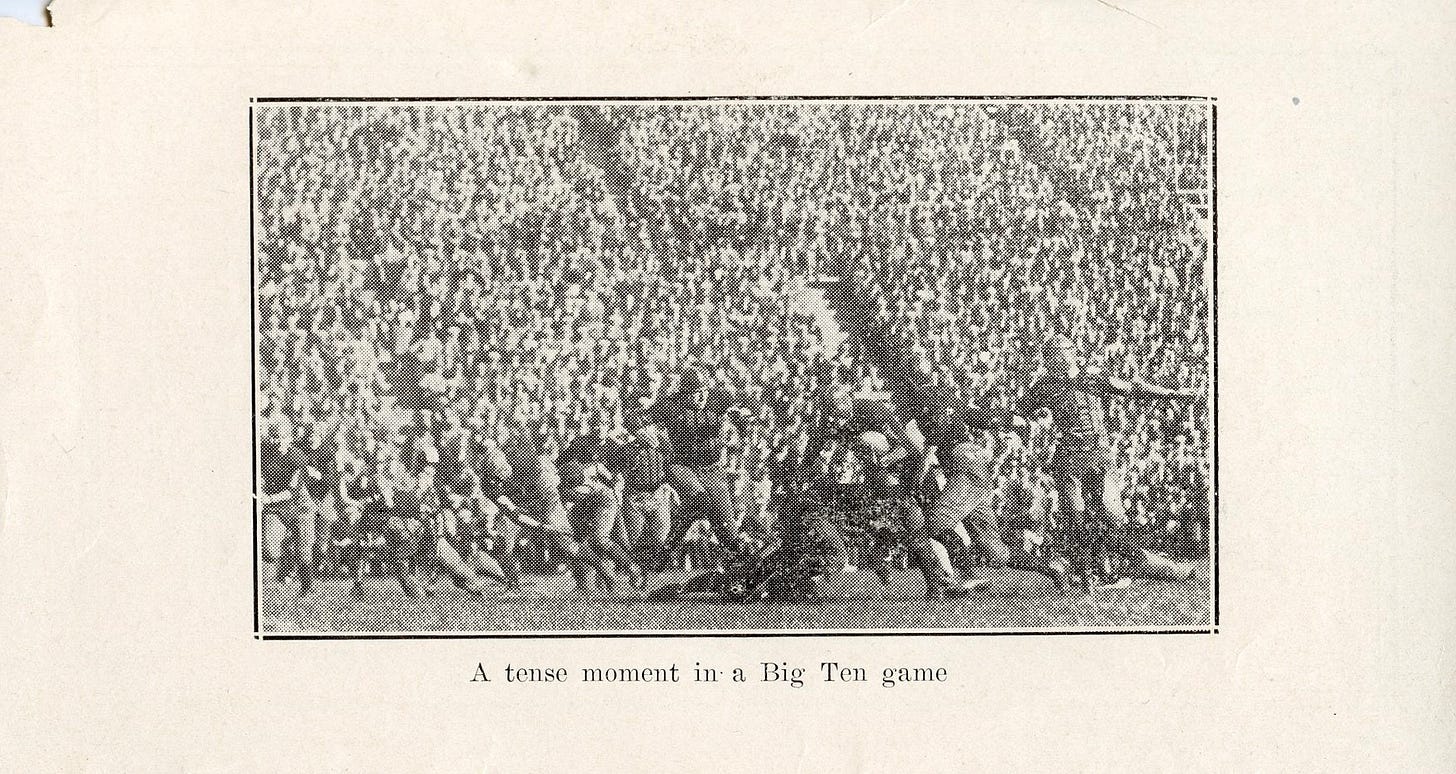

Mentioned at the bottom of the page are "University Events," with the first activity being "Athletic Events." The brochure's facing page has an image of an Iowa football home game, suggesting their football broadcasts had an outsized audience.

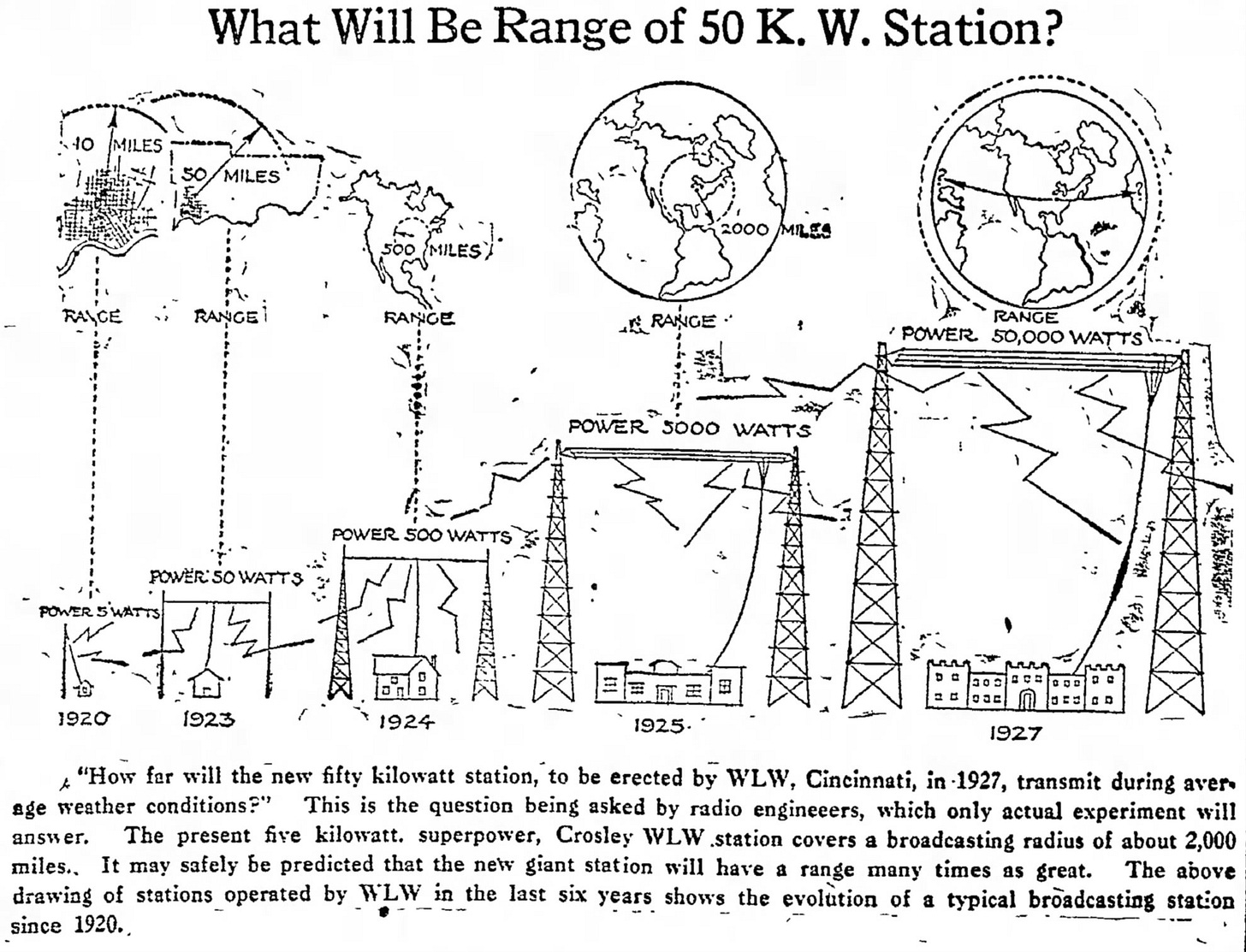

WSUI broadcasted from remote locations early on, as they did from the State Fair in July 1925, but there were limits. They covered only the first four home games and none of the away games that year. By 1926, however, some radio stations broadcast from remote locations. WGN in Chicago covered a key Big Ten game each week. At the same time, WOC from the Quad Cities offered covered an away game or two as stations battled to build taller towers with more powerful transmitters capable of sending their signal undetermined distances.

The popularity of football game broadcasts grew in 1926. WSUI continued broadcasting Hawkeye home games and caught the nationwide fever by running the play-by-play of the Army-Navy game played at Soldier Field in Chicago. They broadcast from a local newspaper office and likely reported the game as the details came over the wire.

The popularity of football radio casts was not without problems. It was not that they were unpopular; they became too popular, which led to concerns about their impact on game attendance and ticket sales. Since Iowa's Athletic Department was self-funded and football ticket sales dominated their revenues, the Athletic Department pressured the Engineering Department to suspend their football broadcasts.

Schools across the country ran into the same issue, and bans of one sort or another occurred among schools and conferences over the next five or six years, but WSUI's ban lasted only one week. The hue and cry were too much, and they quickly reversed the unpopular decision.

Meanwhile, for-profit radio stations initially earned their money from companies sponsoring entire shows, but they began selling 30-second and one-minute commercial slots at prices many more businesses could afford. That grew their market and provided the money to buy the broadcast rights for games, giving exclusivity to the stations and cash to the athletic department.

Broadcast bans resurfaced in the early 1950s when television began taking center stage. The continued reluctance of colleges to commercialize their football programs in the 1950s opened the door to the NFL, which was not shy about making money from its product.

Like other government-funded stations, WSUI remained in state hands and operates today as a public radio station and a member of the Iowa Public Radio network. They broadcast Hawkeye games with student talent into the 1960s and perhaps later. Still, nothing could match the excitement of those early days when they experimented with new technology while learning which topics held interest for their audience.

Football Archaeology is reader-supported. Click here to buy one of my books or otherwise support the site.

That is great. The Wisconsin game was not scheduled for broadcast a month or two before the game, but the snow would have kept them away. I considered including an image of the game from Iowa's yearbook, but sounds like the game is a good topic for a Tidbit.

Maybe the reason only 4 home games were broadcast in 1925 is because the 5th (and last) home game (against Wisconsin) was played in a blizzard. There were 34 fumbles in the game, 17 in the first quarter alone.