Today's Tidbit... Yard Lines and Lime Burns

I was not there to witness it, but I've heard the Egyptians began building their pyramids 5,000 years ago. Somehow, they found the means to cut massive stone blocks, move them from the quarry to the building site, and lift them into alignment where they remain today. Yet, despite humans possessing those skills for ages, Americans in the 1920s sometimes struggled to chalk football fields with straight lines.

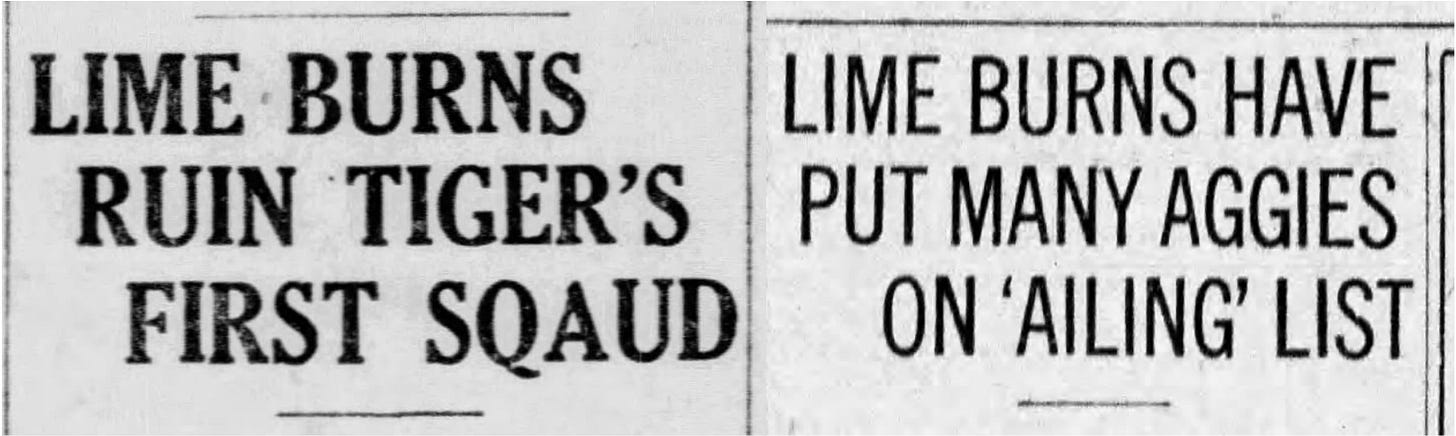

Despite the occasional crooked line, the bigger challenge for football players of old was the lines themselves because the yard lines were sometimes marked with lime rather than chalk, leading to players acquiring lime burns. Concerns about lime, also known as quicklime or unslaked lime, first appeared in the 1910s, likely due to the increased use of concrete and the resulting availability of lime. Reports of lime burns died out in the 1950s as states banned its use at sports facilities.

The problem with using lime for field marking is that lime mixed with water forms calcium hydroxide (hydrated lime), and the chemical reaction can generate enough heat to cause nearby materials to combust. One reason for using lime was that lines marked with lime did not wash away as quickly as those marked with chalk, so they used lime after or in anticipation of rain. Of course, newly applied lime in rainy conditions often remained caustic at game time, so players landing on the markings could suffer burns as a result. Even on dry fields, lime caused problems when it entered the eyes or nose, landed on abrasions, or became caught underneath sweaty players' pants, jerseys, or socks.

Some players bled from their wounds during games, with post-game hospitalizations needed to avoid infections in the days before antibiotics. After games in wet conditions, some teams had six or seven starters sidelined due to these burns.

Besides avoiding the use of lime, there were only a few remedies. One was to mark the yard lines every ten yards rather than every five, sometimes adding short lines extending from the sidelines at five-yard line intervals.

Another solution came from Dr. R. B. Lawson, an anatomy professor and sports director at North Carolina, whose letter to the editor sent to every newspaper in the state, blasted Wake Forest for applying lime without soaking it in water for 48 hours before its application. Lawson convinced the referee of the 1920 Wake Forest game to call timeout whenever players needed lime removed from their bodies and uniforms.

By the 1950s, lime was fading from use, and lime burns increasingly occurred only when applied due to ignorance or error.

Sometimes the good old days weren't as good as they appear, and field markings leading to lime burns certainly fit that category.

Football Archaeology is reader-supported. Click here to buy one of my books or otherwise support the site.

I am glad you added that you were not present at the time of the pyramids. There were rumors that you might have been a stone cutter near the Nile back in the day, Lol.

A great look back at some of the ramifications of marking the field. Super job on this research and write up to tell us all about it!