W. R. Crowley And His 1934 Rule Book

Note: If you support Trump and his fascist ICE goons, you are not welcome here. While I largely keep this blog focused on old-time football, our nation is in crisis and decent people need to speak up. Please find your way to make your voice known.

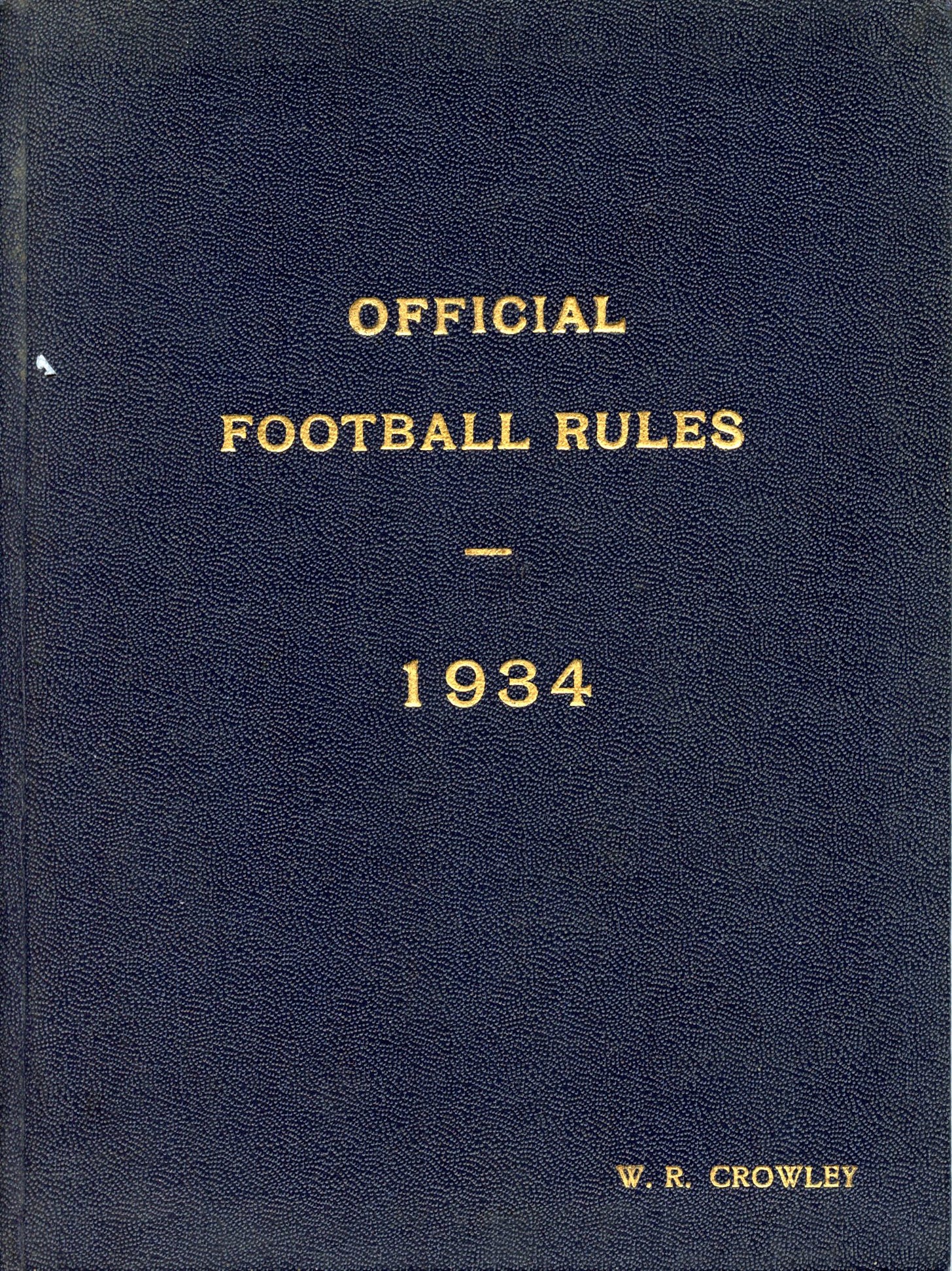

Most football officials are human and make mistakes, but the advent of instant replay has eliminated their most grievous errors. Despite their faults, football would be an absolute mess without the striped lads, and with that thought in mind, I recently acquired a 1934 rule book once owned by a top official, W. R. Crowley.

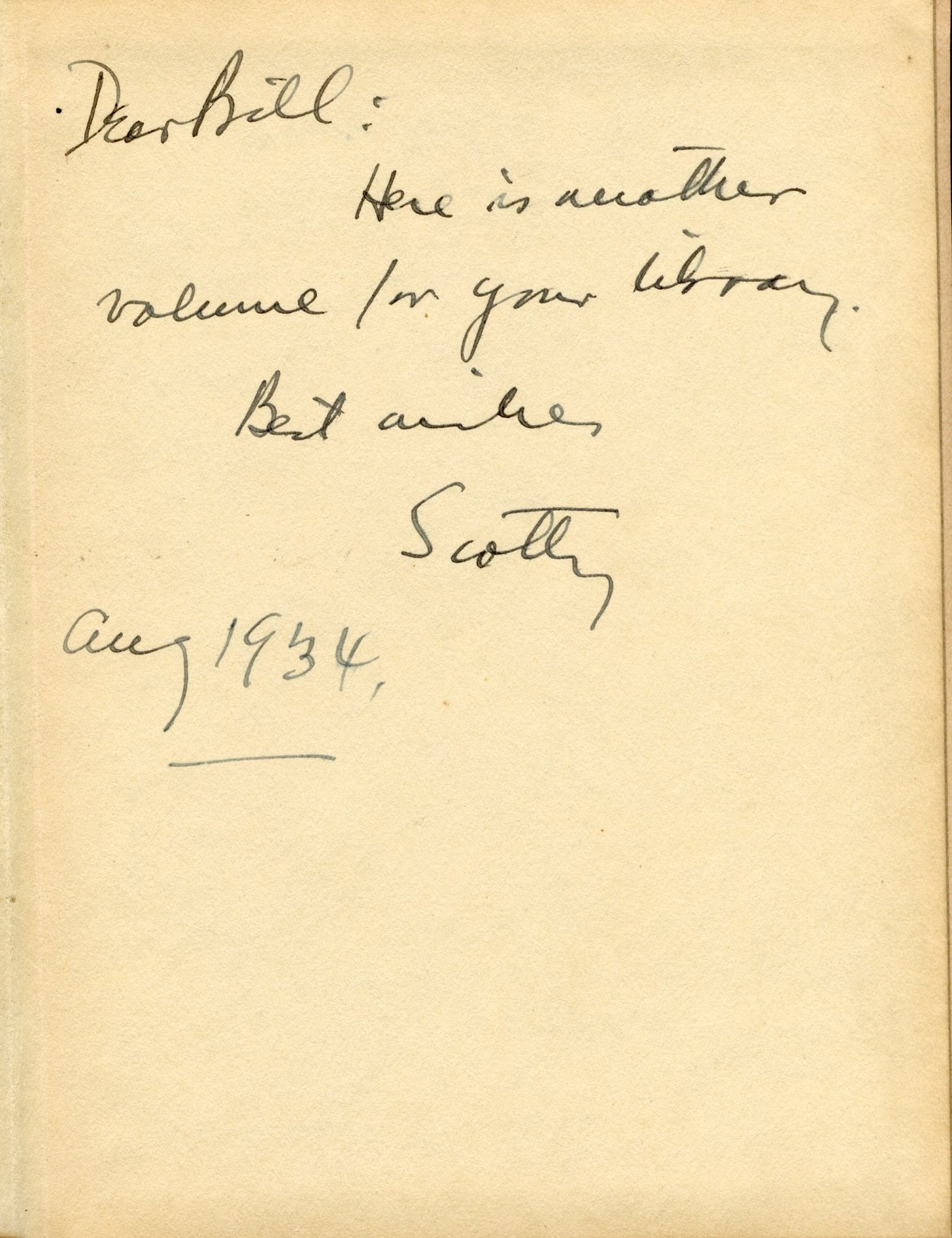

The rule book has a leather cover and was sent to him by Scotty, who is unidentified but may have worked for Spalding, the publisher of the rule book, or been involved in the rulemaking process.

It’s the second personalized and bound rule book in my collection. The other is a 1920 edition once owned by Amos Alonzo Stagg, which I described previously:

Crowley represents a bygone era. Many of the best football officials before WWII were star athletes in their day who lacked the opportunity or chose not to pursue pro football. In part because of their fame as players, game officials were minor celebrities with reputations for how they managed games. They were often quoted about which teams were the best in the league or region, and the details of games they officiated.

As officials organized into regional associations in the 1920s, they achieved equal footing with the game’s coaches in recommending rule changes. Crowley was in the middle of the move to consistently train and test officials, independently assign them to games, and evaluate their performance, so the cream rose to the top. Crowley was among the cream.

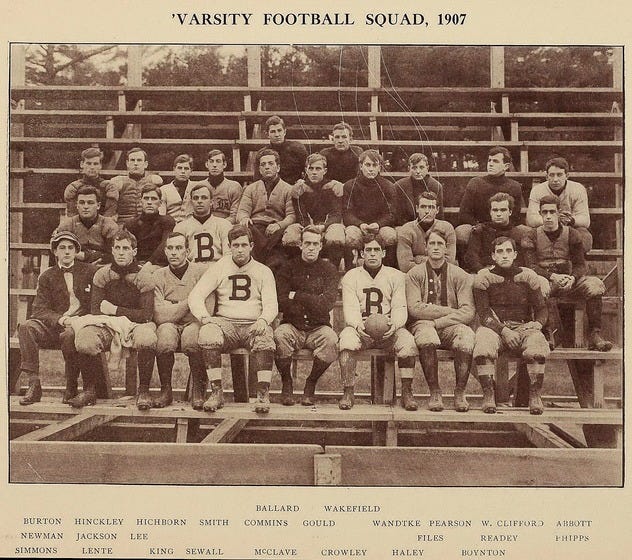

He grew up in Bangor, Maine, and attended Bowdoin College, where he captained the 1907 football team.

After college, he landed in New York City, working for Longans, Green and Co., a British scientific and literary publishing house, and began officiating NYC prep football games before moving to college games. He worked with every leading official of his day from the Northeast and Midwest, and consistently handled big Northeastern games or tough assignments, especially in the 1920s. A sampling of the games he worked includes:

1919, 1921, 1922 Harvard-Centre

1922 Harvard-Florida (Florida’s first game versus an Eastern power)

1922-1926, 1930 Army-Navy (1926 game at Soldier Field in Chicago)

1928-1929 Harvard-Yale

1934 Rose Bowl

1934 Harvard-Princeton (after they did not play for seven years)

Crowley was an officer of the Eastern Football Officials Association for many years, serving as its president in the early to mid-1930s, during which he received the rule book from Scotty. The group’s recommendations to the NCAA Rules Committee during that period demonstrated once and for all that officials do not always get it right. For example, they suggested:

Eliminating the PAT and awarding 1 point per first down (Pop Warner also supported this idea)

Adding a 5-minute overtime system for tie games

Returning the goal posts to the goal line

Having referees announce all rulings

Moving the hash marks from 10 yards to 15 from the sideline (it’s 20 today, for college)

A 1933 Eastern Officials recommendation would have given teams a fifth down when inside the 20. Teams between their own goal line and the 20, what the officials called the “torrid zone,” were reluctant to open their playbooks and often punted on early downs. The officials thought an additional down would encourage teams to take a chance at rushing for a first down.

Likewise, when inside the “frigid zone,” what we now call the red zone, defenses had less space to cover, and stiffened. Adding a down would contribute to more scoring. That never happened, but people who were at the football table thought it was a good idea.

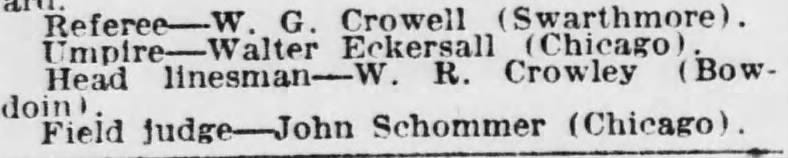

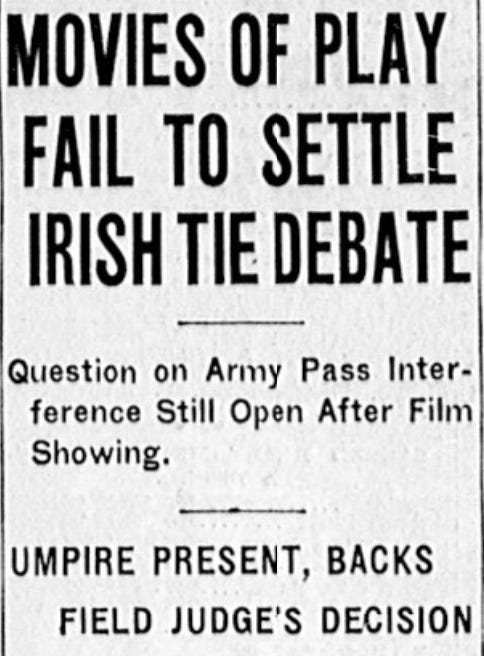

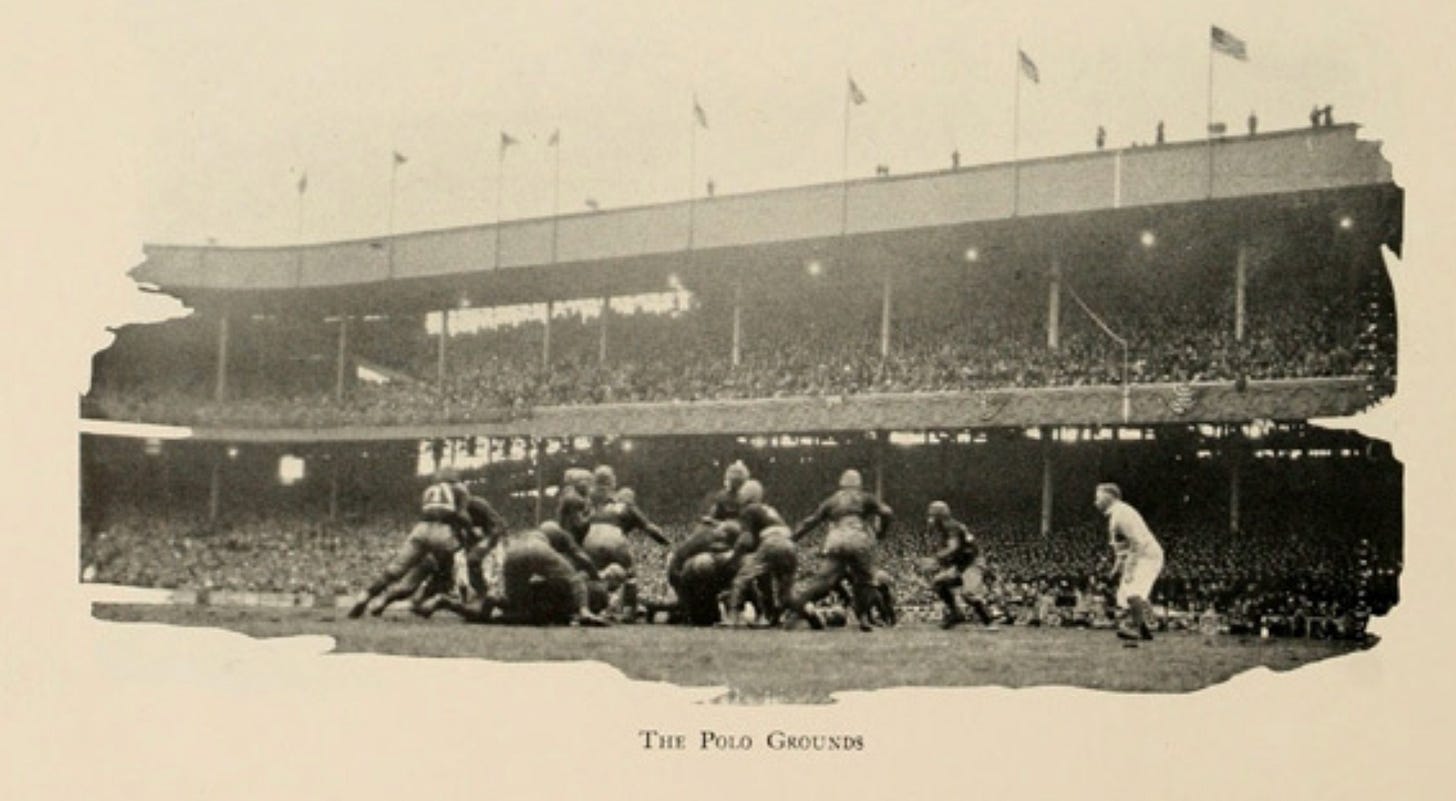

Crowley was involved in few controversial calls on the field. One came when Notre Dame played Army at Yankee Stadium in 1935. In the last minute of the game, Notre Dame’s Bill Shakespeare threw a pass into triple coverage near the goal line. The field judge called Army for pass interference, and Crowley backed him up, saying the defender grabbed the receiver’s arm. Notre Dame scored on the next play, the game ending in a tie.

A review of the “motion pictures” the next day led some reporters to suggest the call was incorrect. It took several hours back to develop film in 1935, so the idea of instant replay was beyond foreign to them. Film technology allowed coaches and others to break down plays and evaluate teams, but it took hours to develop and dry the film, so it was not an in-game technology. So, the ruling stood as called.

Here’s a video of the disputed play. The prior play, which starts at 1:18 and was not in dispute, saw Army knock down a pass at the goal line. My expert analysis of the next play agrees with Crowley: the Army defender grabbed the Notre Dame receiver’s arm shortly before the pass arrived. It’s hard to know how closely officials called pass interference at the time, but the movies I’ve watched says the defense had a lot of liberties. Maybe it came down to material advantage.

As it turns out, officials like Crowley often made the right call without the assistance of instant replay.

Crowley worked college games through the 1941 season. He spent the war years as president of the Savannah, Georgia, shipyards, overseeing the production and launch of 88 Liberty ships (only 3% of the total, but still). W. R. retired after the war and was not directly involved in football, though he was asked and periodically spoke out against the influence of gambling and the commercialization of the college game.

After researching Crowley, I’ve decided I like him. Seems like a good guy. But, who the hell was Scotty?

Regular readers support Football Archaeology. If you enjoy my work, get a paid subscription, buy me a coffee, or purchase a book.

A point for every first down...interesting

Appreciate your work and that you take a stand. Convinced me to join.