Walter Camp and Football's Road Not Taken

The history of football equipment includes long-forgotten devices that never gained the traction their inventors sought. For example, two Michigan inventors earned a patent for adding beads to the bars of face masks, hoping to prevent face masking.

The same situation applies to ideas for potential rule changes, such as the one calling to number the yard lines from 0 to 100 rather than from 0 to 50 on either side of midfield. Whether applied to the game's equipment or rules, we evaluate suggested enhancements as we do ideas in brainstorming sessions where there are no bad ideas. We politely listen to every idea, write each one on the board, and immediately ignore the crazy ones, never thinking about them again.

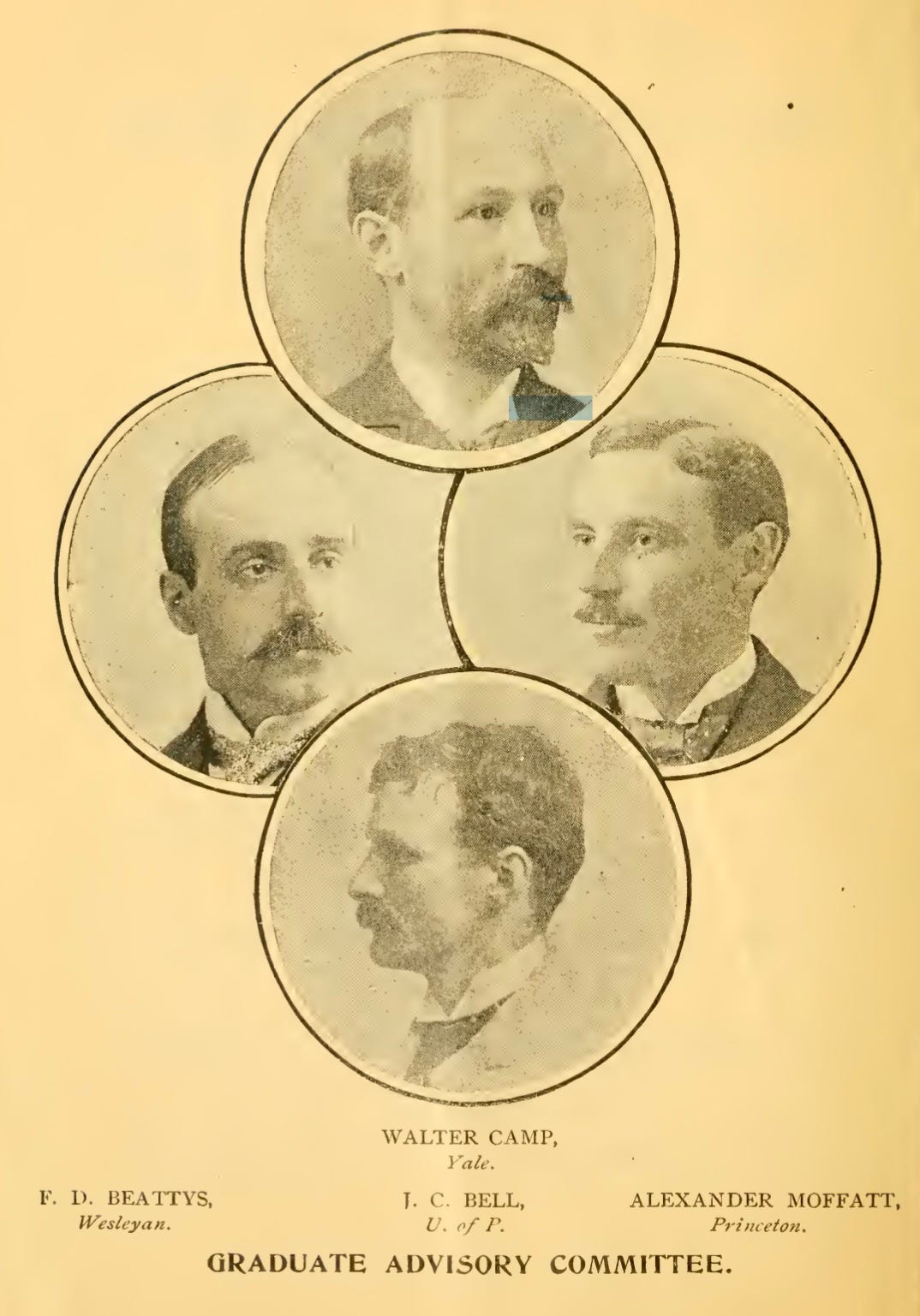

Similarly, when we look at football history, we emphasize rule changes that clearly altered the game’s direction, such as the system of downs, the forward pass, and the introduction of hash marks. However, we ignore ideas that received consideration but were never adopted, especially those that might have significantly affected the game. Those ideas are the roads not taken, one of which appears in a January 1893 issue of Harper's Weekly, authored by Walter Camp.

Camp was a prolific writer and was not one to toss out crazy ideas. If he had a crazy thought, he would not have published it in Harper's Weekly, one of the most widely read periodicals of the time. The article, A Plea For The Wedge In Football, saw Camp argue not to limit the wedge's use in football. Power and close formation play, like the wedge, developed due to an 1888 rule allowing tackling above the knees rather than the waist. The rule made open-field tackling more effective, lessening the advantages of open play versus power and close-formation football.

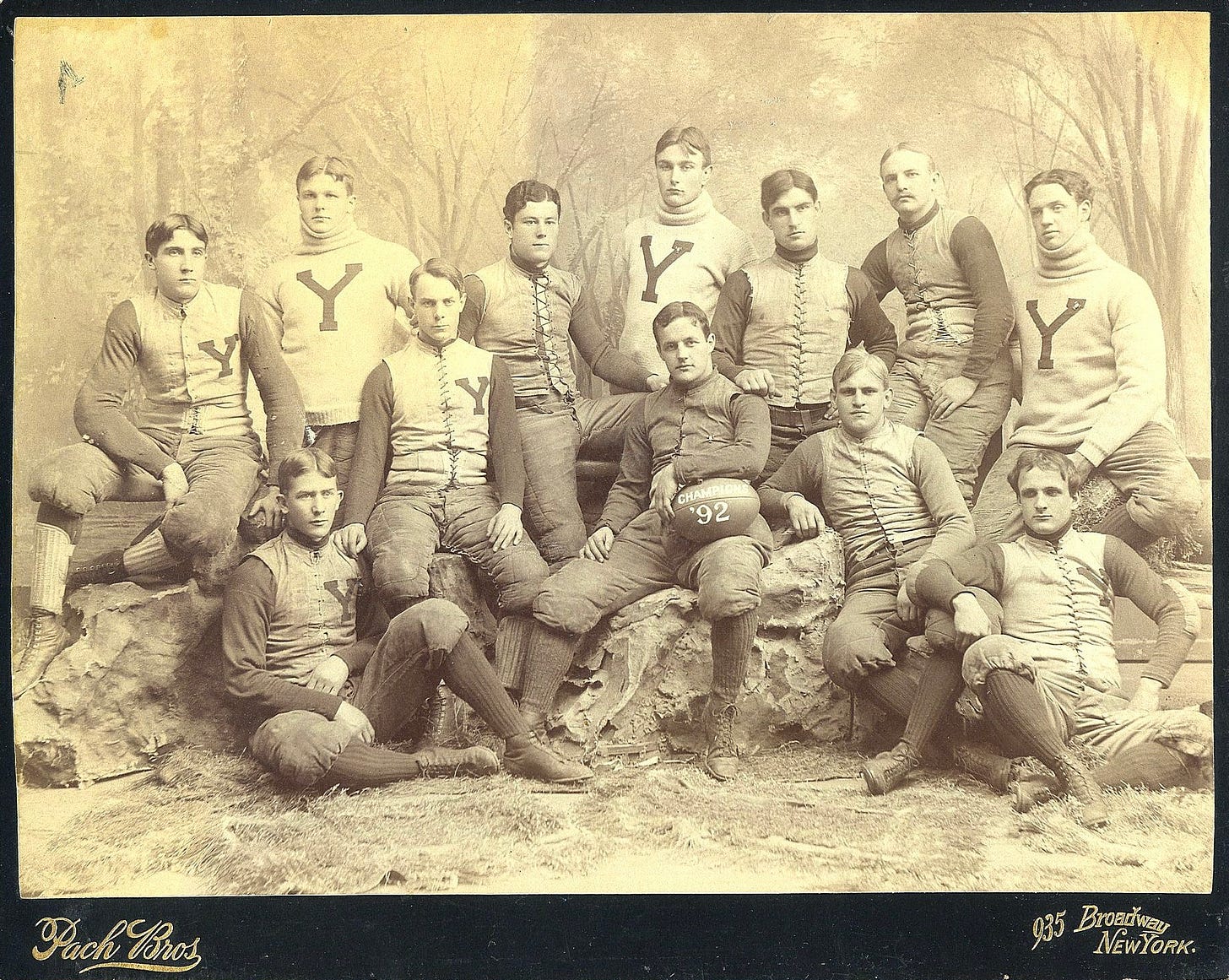

Princeton introduced its V Trick in 1884, and soon every team ran the wedge, culminating in Harvard's Flying Wedge in 1892. While wedge plays were effective if you were bigger and more powerful than your opponent, fans enjoyed it less than the open game. The wedge and the various mass plays that developed over the next few years also made football far more dangerous and required a slew of rules to correct it over the next few decades. But things might have gone differently had football listened to Walter Camp in 1893.

Complaints about the wedge were becoming common, and many suggested rules to ban the wedge; Camp argued that prohibiting the wedge would encounter three problems. First, if the rules restricted the number of players that could form together when blocking, what number would they choose, and would it apply only at the line of scrimmage or across the field? Second, Camp thought a rule that kept teammates from holding one another would be challenging to officiate, especially in piles. (Football allowed teammates to pull, throw, and drag runners forward at the time.)

Some suggested rules alternatively banning or requiring certain offensive formations. However, Camp strongly opposed rules restricting how the offense could align because they infringed on the team captain's creativity, which he thought was "one of the chief charms of the game." Football still does not restrict the placement of defensive players as long as they stay behind their line of scrimmage, and in 1893, football still did not limit the positioning of offensive players. They could line up anywhere and move in any direction pre-snap as long as they stayed behind the line of scrimmage. (Hello Canada!) While most teams lined up in the Traditional T or similar close formations that resembled a scrum, they did so by convention, not by rule.

Camp was not a fan of the wedge per se but thought football had come to value possessing the ball too much. He preferred to limit the wedge indirectly. Rather than restricting the wedge, Camp argued for a horizontal movement requirement. Specifically, he wanted a rule forcing teams to move the ball twenty or more yards horizontally at least once every three offensive plays, or at least they had to do so if they had not earned a first down in the first two plays of a series. He believed the rule would:

...probably stimulate kicking, and especially long passes toward the ends as well as end running, and these are the features which please not alone the ordinary spectator, but every football player who watches great games.

Camp, Walter, 'A Plea For The Wedge In Football,' Harper's Weekly, January 14, 1893.

Had this rule or one like it been adopted, at least one of every three plays would have been "open." Presumably, teams would not have optimized their offenses to run it up the gut and instead adopted strategies to regularly move the ball at least a third of the field's width. Likewise, period defenses would have adapted to open offenses by playing more defenders wide or off the line, opening opportunities in the middle for plays that did not require wedge blocking. Football could have avoided many of the ill effects of the wedge and mass play, but it did not.

Football continued requiring vertical movement to retain possession of the ball but never adopted Camp's horizontal requirement. Instead, the game continued down the wedge and mass play path, ultimately needing a series of rules to limit the effects of mass play. By 1894, the rules limited offenses to three players in motion at the snap and one man in 1885. The 1886 rules required five men on the line of scrimmage at the snap, while the forward pass and onside kick from scrimmage became legal in 1906. (Canadian football did not allow blocking until 1920, so they never adopted the mass game and or needed to restrict the number of offensive players in motion, at least for that reason.)

Had the horizontal rule been enacted, American football might have developed along a different path. It might not have needed rules restricting the positioning of offensive players. The game might have developed more diverse playing styles and formations, more lateraling, and it might never have needed to implement the forward pass. Of course, things did not happen that way, but while Camp’s horizontal movement idea is little known, it might be one of the game's great "what ifs," one of the roads not taken.

Football Archaeology is reader-supported. Click here to buy one of my books or otherwise support the site.