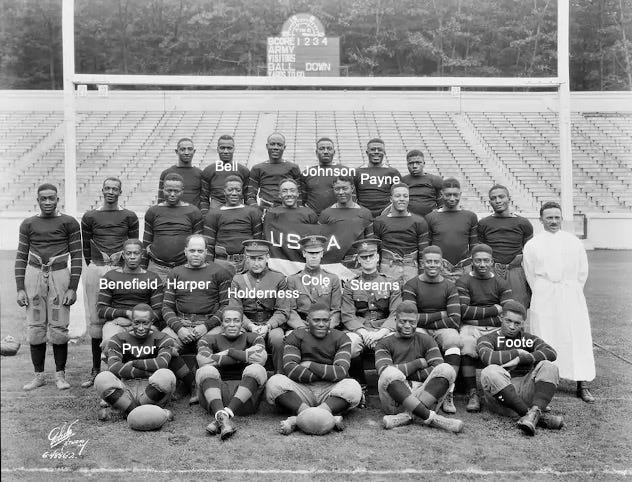

My May 2021 blog post, The Mystery of the West Point Cavalry Detachment Football Team, told the story of the National Archives' discovery of two mid-1920s photographs of a football team posing in West Point's Michie Stadium. The images are notable because the players in the pictures are black, despite West Point's varsity football team remaining all-white for another forty years. Unfortunately, neither the National Archives' announcement nor a follow-up Washington Post article identified the members of the team, their opponents, or how they performed. The men were identified only as members of the 1925 or 1926 West Point Cavalry Detachment.

My article focused on the team during the mid-1920s and showed the cavalrymen were overwhelmed in games against higher-level competition. It also listed the names of seventeen players from the 1925-1926 teams, without matching the names to the individuals in the images. Still, the article provided the names and scant details about the players in the hope that their descendants might come across the information to reveal a previously unknown chapter in one of their ancestor's lives.

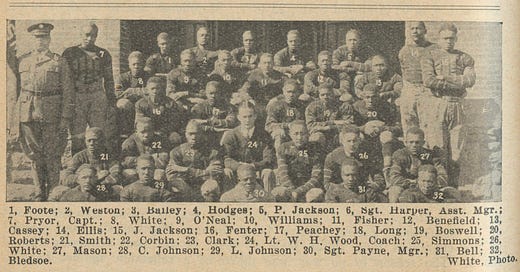

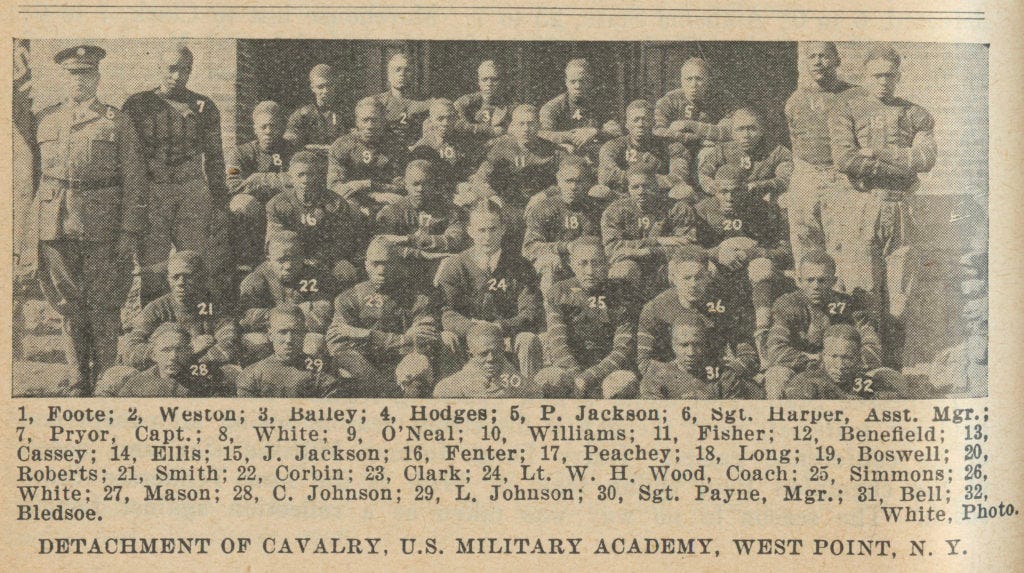

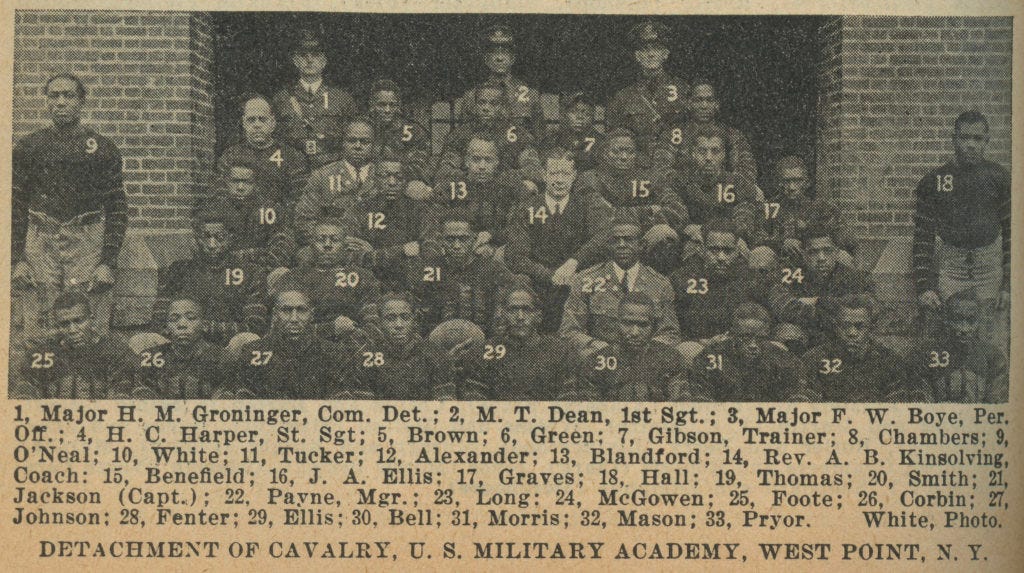

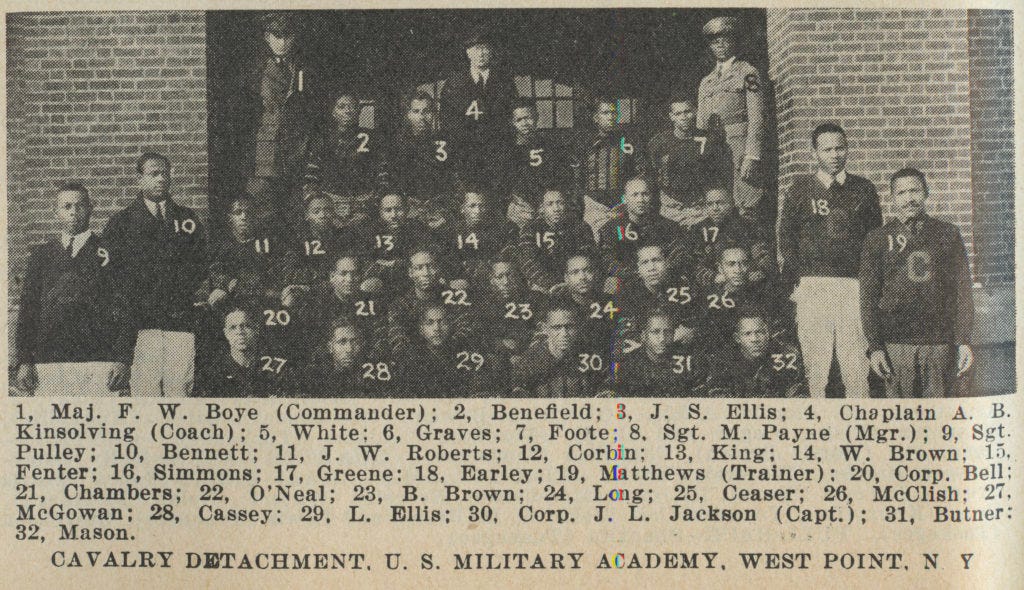

After publishing the first story, further research uncovered additional images and information that shed new light on the team. As a result, we now have a better sense of the players' backgrounds, their competitiveness on the football field, and what became of them in the ensuing decades. The key to gathering additional information on these men was locating the 1928, 1929, and 1930 team pictures, with each individual identified by surname. Those images and surnames enabled research on the individuals using ancestry.com and similar sources, as well as visual matching the faces of the 1925-1926 team against later photos. To date, one-third of the men in the 1925 team picture have been identified and biographical information has been found for others.

The following expands on the original story with the information learned to date.

The West Point Cavalry Detachment Football Team

Historically, the United States Military Academy (West Point) taught a mix of military and traditional academic subjects, and the teaching of military topics (e.g., artillery and cavalry) was assisted by active-duty enlisted personnel. Other groups of enlisted personnel stationed at West Point provided military police, dining, medical, and other services needed to run the institution.

From 1907 to 1947, up to 220 black enlisted men from the 9th or 10th Cavalry manned West Point's Cavalry Detachment. Commonly known as "Buffalo Soldiers," the men cared for the horses and taught horsemanship and cavalry tactics to West Point's cadets and other duties. After WWII, the U.S. Army eliminated the Cavalry Detachment as armored vehicles and helicopters substituted for horses on the modern battlefield.

The Men

Most Buffalo Soldiers at West Point were born or raised in the rural South, and most went directly to West Point after enlisting for their on-the-job training. (Enlistees of the time chose the unit and location of their initial assignment.) Some became career soldiers; others left the service only to reenlist during WWII.

America had a segregated military until 1948. Despite receiving the same pay as white soldiers of the same rank, black soldiers were second-class citizens. With limited exceptions, they could not become officers. The U.S. Army had only seven black officers in 1916, four of whom were chaplains. In each case, they commanded or pastored only other black soldiers.

Black soldiers were commonly relegated to labor battalions. The only black soldiers who saw frontline duty during WWI did so under French command. Most black soldiers who went to France were stevedores, foresters, or performed other physical labor. As they labored, white Americans who died in battle were buried where they fell. Post-Armistice, the Army needed to move those bodies from their temporary graves to central cemeteries. What race of soldier do you suppose dug up the putrefying bodies of the dead? At West Point, only the Cavalry Detachment soldiers spent time during winter cutting ice from nearby lakes. The racist attitudes within the Army and in American society generally continued during WWII when Senator John Bankhead of Alabama requested that Chief of Staff George C. Marshall keep Northern black soldiers out of the South so they would not bring their ideas and behavior with them. In a sign of things to come, General Marshall ignored the request.

That the Cavalry Detachment soldiers fielded athletic teams is not surprising. The U.S. Army and Navy have fielded base or ship athletic teams since the late 1800s. Best known to the public are all-star teams that played outside competition for public relations purposes, including the teams that played in the 1918 and 1919 Rose Bowls and the 1944 Cotton Bowl. However, most military teams played in intramural leagues organized at the company, regiment, or similar levels at large bases. Of course, some intramural teams also played outside competition, but where did an all-black football team in rural New York State in the 1920s find teams willing to meet on the friendly fields of strife? Major League Baseball was all white. The early NFL had a few black players in the 1920s, but they were banned in 1933 and did not return until 1946. Similarly, the predominantly white colleges in the North might have had one or two black players on their rosters -most had none- but none played black colleges. So, who did the Cavalry Detachment football team play?

The Teams

As expected, the Cavalry Detachment's sports team sought games against other African-American teams in New York and surrounding states. The Detachment's 1925 basketball team played the famous 369th Infantry Regiment, a New York State National Guard unit known as the Harlem Hellfighters. The 369th served under French command in WWI, spending more time on the frontlines than any American unit. The Detachment also scheduled Lincoln University in Philadelphia, then the top black college football team in the North. Their 1925 and 1926 games earned previews and game reports in the Pittsburgh Courier, a black newspaper. Unfortunately, the white press did not cover either game. Regardless, Lincoln University lanced the Cavalry team 66-0 in 1925 and 87-0 in 1926. Lincoln did the same to a few college teams those years, but the scores tell us the Cavalrymen were not competitive with teams at Lincoln's level.

Given the segregation of higher-level sports, one might assume the many town teams, athletic clubs, and semi-pro teams of the era had similarly segregated schedules, but that was not the case. We know that, in part, because period newspapers universally describe teams comprised of black players as "colored," often as part of the team names (e.g., the Paterson Colored Pros or Paterson Pros (colored)). Ninety years later, that editorial convention helps distinguish white from black teams, revealing that while games between black and white teams were not the norm, they were sufficiently frequent that sportswriters did not mention interracial games as being unusual. (Sportswriters sometimes made other racist comments, but the simple playing of games between white and black teams did not warrant commentary.)

What distinguishes the West Point Cavalry Detachment team is not that they played some games against white teams; they are remarkable for playing most or all their games against white teams some seasons. Moreover, West Point hosted a multi-sport enlisted men's league among its functional units (e.g., Cavalry, Artillery, Service, and Engineers). Since the Cavalry Detachment was the only unit at West Point with black soldiers, their intramural competition was all white. The available records show the Cavalry team was competitive in the enlisted men's league in the mid-1920s, winning some games and losing others.

As the Twenties turned to the Thirties, the Detachment team became far more competitive, likely due to an influx of talent, but coaching may have also helped the situation. The 1928 detachment team picture below shows Lt. W. H. Wood (#24) as the team coach. Although his name is little recognized today, Wood won nine letters at Johns Hopkins University before transferring to West Point, winning twelve more there, and earning first-team All-America honors at fullback in 1925. After graduation, Wood stayed at West Point as an assistant coach for the cadet team and was head coach of the Cavalry Detachment team. (Wood was Army's head coach from 1938 to 1940.)

Rev. Arthur Kinsolving, the West Point Chaplain, replaced Wood as coach in 1929. Having grown up in Brazil, it is unclear where Kinsolving acquired his football expertise, but he coached the team for the next four years, a period in which they noticeably improved.

As confirmed by the championship trophy below, the 1929 Cavalry Detachment team won the West Point Enlisted Men's League. (The discovery of the trophy occurred by happenstance, as documented here.)

Since black and white teams seldom played one another in the 1920s, the number of black teams playing in predominantly white leagues was few. That means the 1929 championship trophy may be the first won by a team of black players competing against teams of white players. (Anyone aware of an earlier team able to stake this claim, please advise.)

Besides winning the Enlisted Men's League, the only known outside game played by the 1929 Cavalry Detachment team was a 31-0 victory over the Kingston Yellow Jackets.

The 1930 team won the Enlisted Men's title as well. One article suggests the team was undefeated and unscored upon several years running, though that report likely concerned only their West Point Enlisted Men's League games since we know they lost at least one outside game each year. Although the cavalrymen continued playing town teams from cities along the Hudson, they also played professional and semi-pro teams from Northern New Jersey. Multiple professional football leagues existed in the 1920s and 1930s, with franchises regularly folding or changing leagues. Unlike today, when the NFL reigns supreme, the top teams from the lesser professional leagues were competitive with the NFL's bottom dwellers. For example, the 1932 Detachment team lost a close game to the Clifton Wessingtons, who then lost a nailbiter to the NFL's Staten Island Stapletons. That said, it is impressive that the cavalrymen of the early Thirties won half their games against professional and semi-pro teams such as the Passaic Red Devils, Clifton Wessingtons, and Paterson Giants.

Additional indications of the Detachment team's competitiveness include their 1931 victory over Lincoln University, which crushed them back in the 1925 and 1926 seasons, and their periodically scrimmaging West Point's varsity. Ultimately, the cavalrymen were likely comparable to a good college team during the late 1920s and early 1930s.

Less information is available about the team after the 1932 season. The 1937 Cavalry Detachment football team played at least one outside game, and the enlisted men's league at West Point played basketball, if not other sports, in 1938. Still, we know little about their participation and performance on athletic fields for much of the 1930s.

Identifying The Team Members

Besides understanding who the Cavalry Detachment team played and how they performed, a primary goal of the research was to identify the players in the 1925-1926 team pictures and obtain a sense of their lives off the playing field. Readers interested in understanding the research and image-matching processes used to gather this information can find an explanation here. The following focuses on the research findings.

The 1925, 1928, 1929, and 1930 team pictures included seventy-six individuals, including seven white officers and an unidentified black physician. The three white officers in the 1925 team picture were relatively easy to identify using West Point yearbook images of the Cavalry officers on the faculty. In addition, each was a West Point graduate and career officer, so their significant paper trails made it straightforward to create their biographies.

The twenty-four players in the 1925 team picture were more challenging. Identifying them required comparing images from the 1928 to 1930 team pictures and a few images found elsewhere. To date, the process has identified seven members in the 1925 team picture and biographical information for five more. Likewise, biographical information was located for the four white officers or coaches in the 1928 to 1930 team pictures and for thirty-seven of the fifty-four black soldiers on those teams.

Broadly, the biographical information tells us most players were born and raised in the rural South. Some migrated north as children, others when they enlisted. Two were born in Oklahoma and descended from Chickasaw Freedmen, African-Americans enslaved by members of the Chickasaw tribe.

Most cavalrymen who played on these teams enlisted in the 1920s. However, some served with the Cavalry or the segregated 25th Infantry Regiment in the Philippines before WWI. A few served in France with stevedore or other labor battalions, while Major Milton T. Dean, who is in the 1929 team picture, was the third highest-ranking African American in the U.S. Armed Forces during the Great War. Dean commanded the 317th Ammunition Train, which fought in the Meuse-Argonne as part of the 92nd Division. Dean had his rank reduced after the war, like many officers who served during the much larger Army of the war years, but Dean's dropping from Major to noncommissioned status was unusual. The dramatic drop showed the Army had little need for black officers between the wars.

Despite the inequity, serving in the Army and at West Point, in particular, was a coveted duty, and a number of the team members became career soldiers. Others left the service before WWII and reenlisted during the war, often becoming noncommissioned officers. Of the forty for whom biographical information was found, seven served during WWI, twenty-one during WWII, and two during the Korean War. Another served in the Merchant Marine during WWII.

One West Point cavalryman who enlisted in April 1929 made the ultimate sacrifice. Lee A. Graves was a starting running back for the Detachment teams of the early 1930s while also playing forward in basketball and second base in baseball. Promoted to corporal by 1939, his role during WWII is unknown, but he became a Chief Warrant Officer before the Korean War. Graves shipped to Korea with the Fifteenth Infantry Regiment, Third Division, and was killed in action in late September 1951.

Summary

The West Point Cavalry Detachment football team provides a window into football, the military, and American society in the 1920s and early 1930s. Their experience illustrates that African Americans enjoyed fewer privileges than their white counterparts. Yet, the sporting world allowed them to hold their own and succeed when competing with whites on equal terms. As pioneers competing in the world of white football, the Detachment teams should be recognized for their advances. Still, they were virtually unknown until the National Archives located their team pictures. This research and extensions that may occur should position the teams and men for their role in breaking down barriers that ultimately led to the desegregation of the Army and subsequent advances that continue to this day.

Next Steps

To date, the research has identified seven of the twenty-four players on the 1925-1926 team, while four remain unnamed. Since there are few apparent resources to identify the remaining men and create their profiles, the only option is to crowdsource the identification process, hoping that descendants of the team members might have information about or images of their ancestors. Of course, the challenge is finding those people.

The hope is that those whose family histories indicate that Grandpa or Great Uncle Charlie served with the West Point Cavalry Detachment during the 1920s and 1930s might come across this site while doing genealogical research. Alternatively, individuals of African American descent who share the team members' surnames -or have a surname one or two branches back in their family trees- could review the players' images and information to determine whether an ancestor might be among those on the teams.

To read more about the team members or to help with the research, go here and click on the appropriate links.

Note: The trophy pictured above is currently on display at the National Archive Museum as part of the All American: The Power of Sports exhibit.

If you enjoyed this article, consider subscribing to my newsletter.

Great article. Would love to connect and exchange information.

I will connect outside the platform.