Who Invented The Hidden Ball Trick, And When?

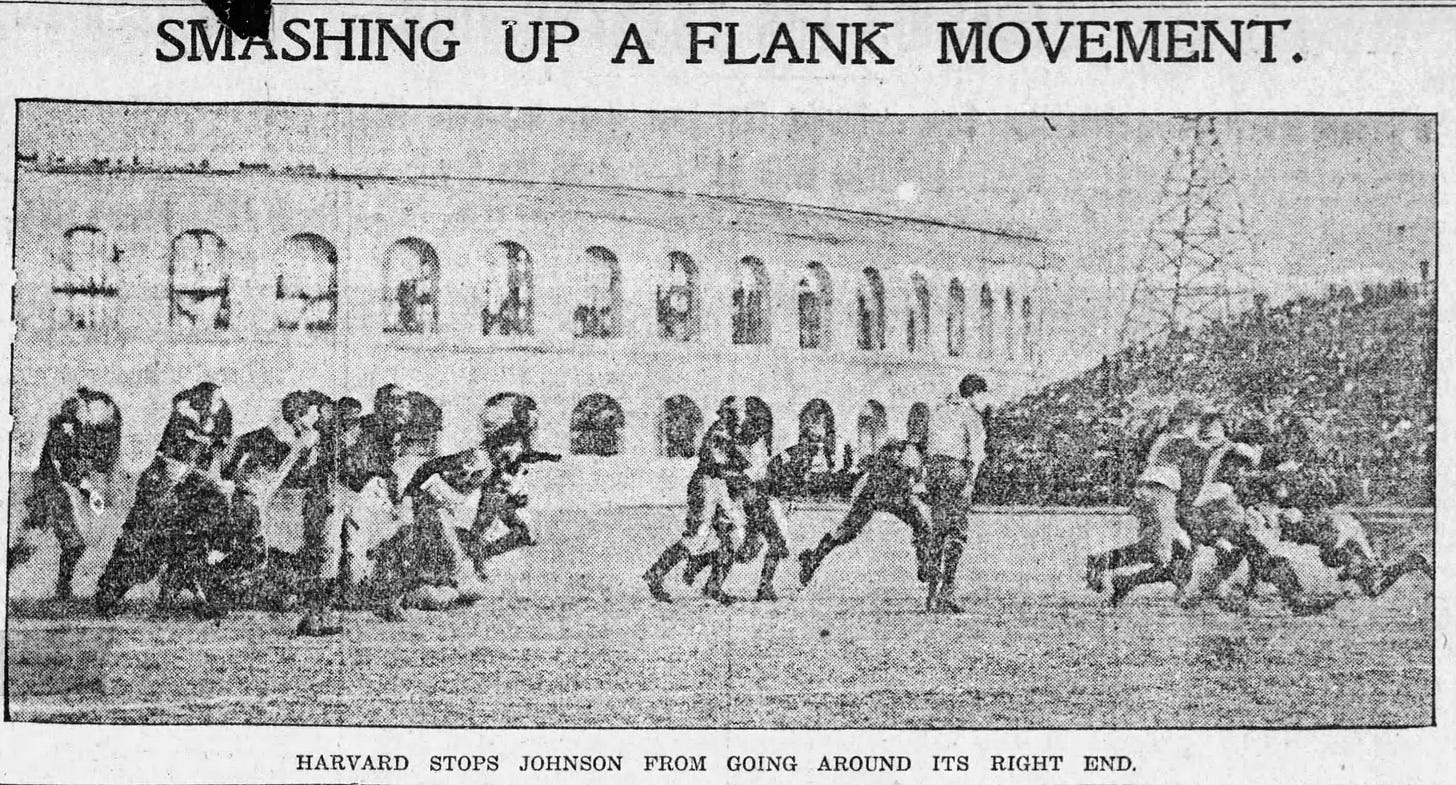

It is often claimed that Pop Warner's Carlisle Indians executed the first hidden ball trick against Harvard in 1903, but that claim is wrong several times over. During the 1903 game, the last game played on Harvard’s Soldiers' Field with the nearly-finished Harvard Stadium looming in the background, Carlisle came close to upsetting the Crimson, as the Bostonians won 12-11.

Game reports and a Pop Warner interview in the next day's Boston Globe tell us the hidden ball trick came when Harvard kicked to Carlisle to start the second half. Executing a play they had practiced for weeks, Carlisle's quarterback, Jimmy Johnson, fielded the kick while the rest of the Carlisle players gathered around him, making it appear they would run forward in a wedge. Instead, Johnson stuffed the ball under the back of guard Charles Dillon's jersey, which had a "stout band of elastic at the bottom." Once inserted under the jersey, the eleven Carlisle players ran in different directions as Dillon, with both arms free, appeared to try to block a few Harvard opponents. Naturally, the Crimson players avoided Dillon, chasing the Carlisle backs instead, and allowed Dillon to pass through and head downfield untouched.

The play became a football legend, largely because it occurred against Harvard. People repeated the story of Carlisle premiering the hidden ball trick against Harvard so often that almost everyone came to believe it.

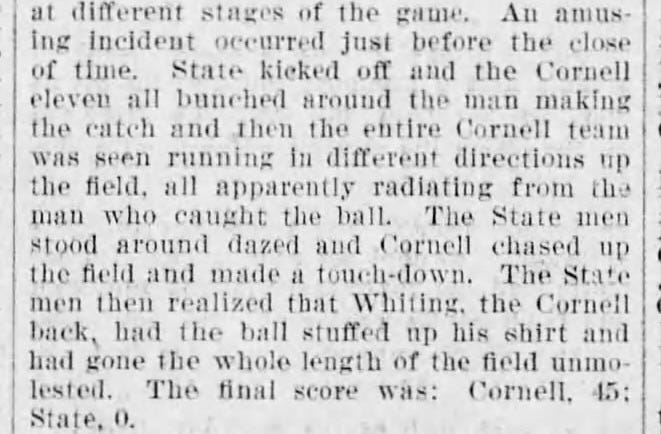

Missing from the telling of the story is that the same issue of the Boston Globe included a Warner interview in which he told reporters he ran the same play when his Cornell team played Penn State in 1897. Cornell was up big on Penn State in the 4th quarter when Penn State kicked off to Cornell. That time, Cornell's quarterback fielded the ball and placed it under the jersey of Whiting, his left halfback. The Penn Staters could not tell who had the ball and allowed Whiting to return it all the way for his sixth touchdown on the day. While the play worked in 1897, Warner realized by 1903 that the deception would likely work better if a lineman carried the hidden ball rather than a back.

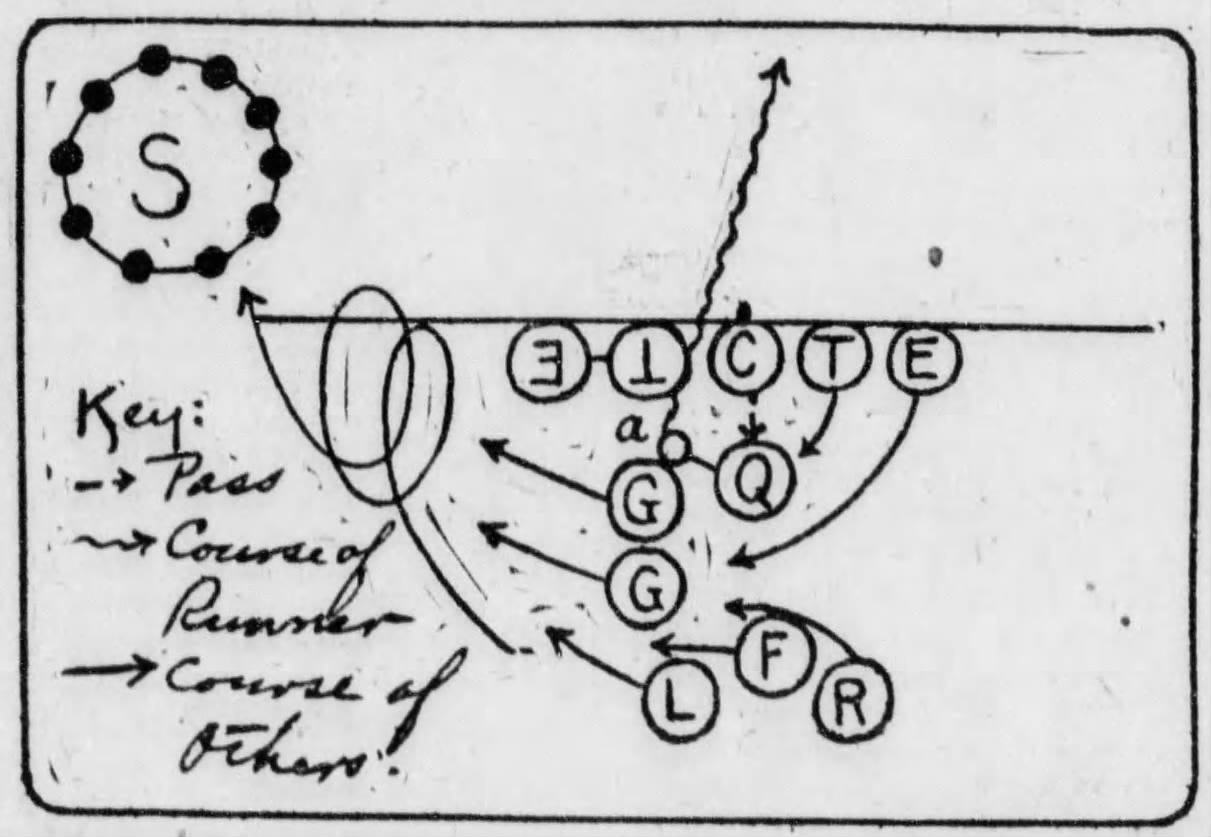

As you might also guess, the Cornell-Penn State game also was not the first appearance of the hidden ball trick. That honor goes to John Heisman's 1895 Auburn team when they played Vanderbilt in Nashville. Heisman had his team execute the play from scrimmage. Back then, offenses were not required to have seven men on the line of scrimmage, so Auburn lined up in a guards tandem formation. Auburn's quarterback, Reynolds Tichenor, received the snap, moved into a revolving wedge, and stuffed the ball under his shirt before squatting down and letting the wedge pass over him. As Vanderbilt tried to tackle someone in the rotating wedge (designated by the encircled S), Tichenor stood up and ran the ball over the goal line.

Contemporary news reports confirm Heisman's account of the Vanderbilt game, in addition to his telling the story and diagramming the play in 1914.

Auburn then used the play a few weeks later against Georgia. That version of the hidden ball trick did not go for a touchdown, but it still caught the eye of the opposing coach, a guy named Pop Warner, who added it to his arsenal of trick plays and adapted it for kickoffs in 1897.

Warner used other trick plays during his career. His Carlisle teams were known for their trickery, as were some of his other teams. While coaching Stanford in the 1920s, he modified a hidden ball trick -the Statue of Liberty- by having the "statue" roll away from the play’s action, a move his team nicknamed the "bootleg," which we've called the tactic ever since.

Football Archaeology is reader-supported. Click here to buy one of my books or otherwise support the site.