A History of Tie Games and Overtime in Football

Given the recent controversy over the NFL's overtime rules, it is worth reviewing the history of tie games in football and the many attempts to eliminate them. Although no one other than Ara Parseghian and Notre Dame likes tie games, they were a regular and accepted part of football for much of the game's history, partly because games between evenly-matched teams were often low-scoring affairs. Take, for instance, the biggest games of the year in early football -the season-ending matches between Princeton and Yale- when six of ten games played between 1877 and 1886 ended as scoreless ties. It seemed at the time that if the two teams had not determined a winner or even scored after their ninety- or seventy-minute games, then it was unlikely that a tie-breaking overtime period would result in a timely resolution.

Low scores and ties remained common in football for decades. Twenty percent of NFL games in 1932 ended in ties, which led the league to abandon the college rule book and create their own in 1933. The NFL rule book included three changes to enhance scoring and reduce ties:

They moved the goal posts from the end line to the goal line, reversing the 1927 switch made under the college rules.

Like the colleges, the NFL added hash marks to the field, which had numerous consequences for opening up offenses. (See here for a full explanation.)

The NFL dropped the rule requiring forward passes to be thrown from five yards or more yards behind the line of scrimmage. This change enabled the quick passing game, gave passers more leeway when scrambling, and had other ramifications.

The NFL's combination of rule changes worked. The 1933 NFL season saw the doubling of made field goals and points scored overall, while the pass completion percentage rose to an astounding 37 percent (not a typo). The result was that less than five percent of games ended in ties. Of course, while the NFL welcomed the substantial tie reduction, the rule changes did not eliminate them. Neither did they create an effective mechanism to handle those ties that occurred, which remains true for the NFL nearly ninety years later.

Another contributor to ties being accepted was that neither college nor professional football had tournaments or playoffs in which one team advanced to the next round. Football also avoided overtime because few teams played in lighted stadiums, so many feared that overtime periods would cause more games to be called due to darkness.

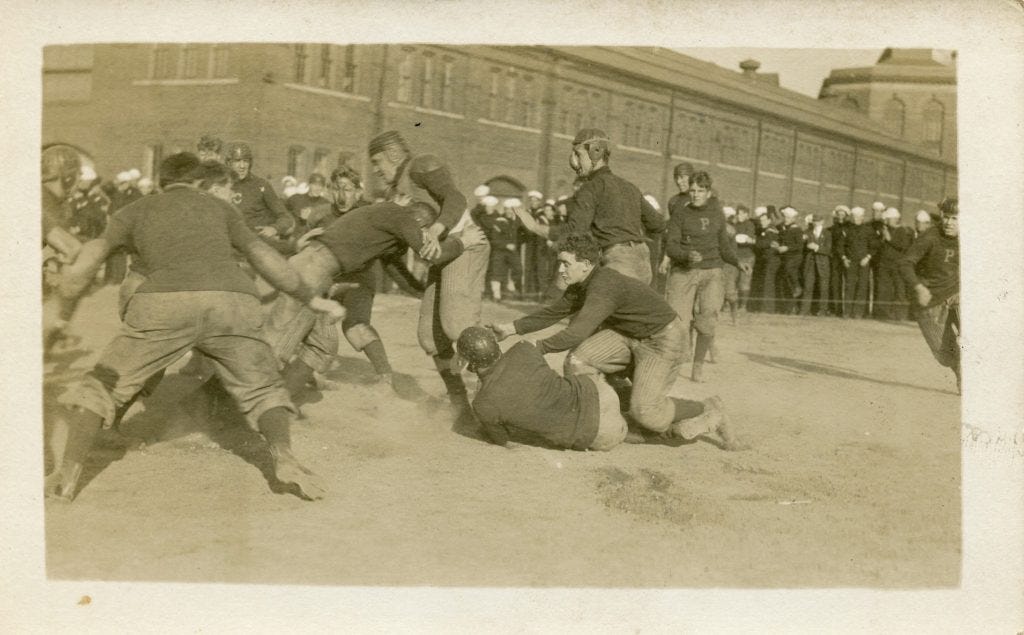

Thankfully, other levels of football had tournaments, and they devised schemes to deal with tie games, though some of those schemes would not be recommended today. The first known football tournaments were those of the pre-WWI U.S. Navy, which had leagues organized by port and class of ship: battleships played battleships, and destroyers played destroyers. In the Atlantic Fleet, the top teams from the ports of Boston, Brooklyn, Philadelphia, and Norfolk advanced to a playoff for the coast championship. It just so happened that a 1915 semifinal game between the U.S.S. Wyoming and U.S.S. South Carolina ended in a tie. Lacking a procedure to advance one of the teams, Navy officials had the teams play a tiebreaker game the following day. The Wyoming team advanced and beat the U.S.S. South Carolina for the championship several days later.

An analogous situation occurred when the Rose Bowl Committee decided that the Western representative for the 1919 Rose Bowl would be the winner of a five-team tournament among the top West Coast service elevens. After a quarterfinal game ended in a tie, the committee compared the two teams' scores against common opponents and chose the Balboa Park Training Station team in San Diego to advance, but they lost to the Mare Island Marines in the semifinals on Christmas Day.

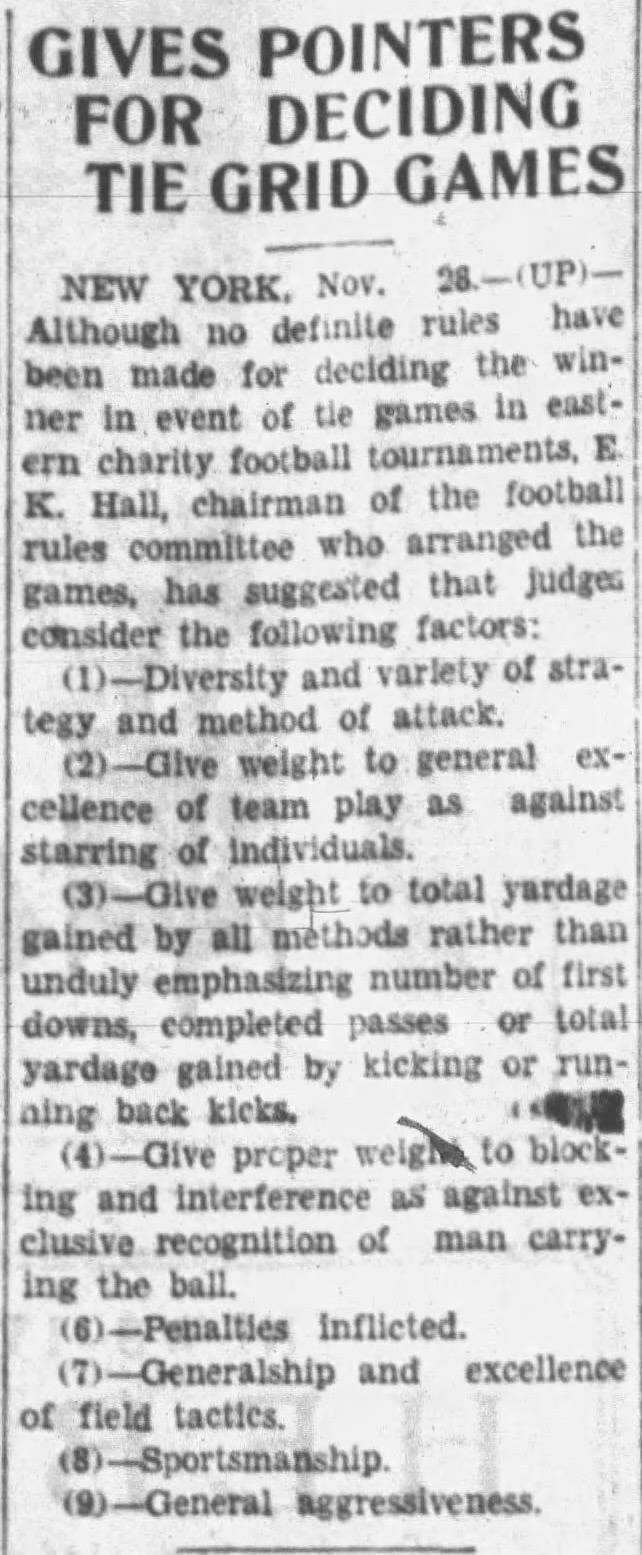

The other level of football in which tournaments became popular was in state high school football championships, where our current tie-breaking schemes originated. Various states used tie-breaking schemes that followed three themes. The first was to decide the game based on chance, which Minnesota did by determining the winner via coin toss in 1920. The second was to use game statistics, awarding the game to the team that most often penetrated their opponent's 5-, 10-, or 20-yard line or the team gaining the most first downs during regulation play. This approach gained backhanded support in 1931 when some colleges played post-season tournaments to raise money for Great Depression charities. E. K. Hall, who succeeded Walter Camp as the college football rules committee secretary, suggested using nine criteria as tiebreakers. Unfortunately, only one of Hall's nine criteria, total yardage gained, used objective game results. Still, even that measure was problematic because football did not yet have a standard system of tracking game statistics.

We can all agree that Hall's system would not solve the NFL's current problem, but some states pursued the third option of deciding tie games on the field during overtime play. For example, California used this approach by 1926, giving each team five plays from the 50-yard line and awarding the game to the team that scored the most points or gained the most yardage. (In the aftermath of the 1932 season, the NFL considered giving each team the ball at their opponent's 10-yard line, with the team using the fewest downs to score a touchdown declared the winner.)

State high school associations used a mishmash of schemes until the 1970s when the modern form of tie-breaking emerged in Kansas. Kansas introduced a high school playoff system in 1969, deciding ties using the game statistics method, which few liked. The Executive Director of the Kansas State High School Activities Association, Brice Durbin, recommended settling ties by giving each team four downs from the 10-yard line. Each team received an equal number of possessions until one outscored the other. Kansas adopted Durbin's system in 1971, and other states followed, as did the NCAA when the Division II and III national championship playoffs began in 1973. The original NCAA version gave each team the ball on the 15-yard line and did not allow defensive scores. Teams began receiving the ball on the 25-yard line starting in 1985, and this approach was implemented at the major college level for bowl games following the 1995 season and for regular-season and bowl games in 1996. The NCAA version of the Kansas Rules works reasonably well by all accounts.

On the other hand, the NFL adopted the "sudden death" plan in 1952 when the Detroit Lions and Los Angeles Rams tied for the National Conference title. The teams played an extra game to determine which would advance to the league championship game, with the league planning to use the sudden-death approach if the game ended in a tie. It did not, but a 1955 exhibition game between the Rams and Giants did. The teams, which received permission to use the sudden death rules if the game ended in a tie, had to use them when the inevitable occurred. The Rams won the toss, received the kick, and Norm Van Brocklin led them on a 70-yard touchdown drive to win the game without the Giants having an offensive opportunity. Sound familiar?

Of course, the primary criticism of the sudden death system is that it does not ensure each team receives an equal number of possessions. Clearly, the NFL understands the sudden death system's inequity and that other football levels use a demonstrably better system. One would think the NFL could swallow its collective pride and admit that an overtime system designed to "just get it over with" is not the best solution. Of course, they could have learned that lesson following the 1955 Rams-Giants game and did not, so there is little reason for optimism.

Football Archaeology is reader-supported. Click here to buy one of my books or otherwise support the site.