Pitt's Role in Player Numbering and Other Numbering Plans

This week's episode of the Pigskin Dispatch Podcast concerned a portion of an October 2023 Factoid Feast that covered a suggestion to number football players 1 through 11. When preparing for the podcast, I did more research and came across new-to-me information about the University of Pittsburgh’s role in player numbering and alternative approaches to the player numbering system that became the standard.

Below are previous stories about the origins of player numbering and wacky numbering systems, such as using four-digit numbers, Roman numerals, and alpha-numeric systems.

I previously credited Pitt with popularizing, not originating player, numbering, but the new-to-me information concerns Karl Davis, who worked at Pitt in 1907. The Origins of Player Numbering story shows that the first known use of numbers on football players was the 1905 Iowa State-Drake game, but Pitt deserves credit for being the first to use player numbers consistently. Davis, whom I was unaware of until this week, worked in publicity at Pitt in 1907 when he came up with the idea of numbering players. Stagg raised the idea six or seven years earlier, but Davis may have been unaware of Stagg's idea and ISU-Drake's use of numbers in 1905.

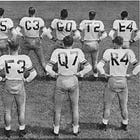

Regardless, Davis claimed in 1941 that he added player numbers to help fans identify who was who. Some early photos show the numbers stitched directly onto the jerseys, while most images show the numbers printed on white rectangular shields sewn on the backs of jerseys. Davis was also in charge of program sales, so he swapped players' numbers weekly to force fans to buy a new program for each game. Over the next decade, other teams used the shield approach because they only wore numbers when their opponent agreed to do the same. Still, it now appears that Pitt's consistent use of numbers had a financial rationale behind its information value.

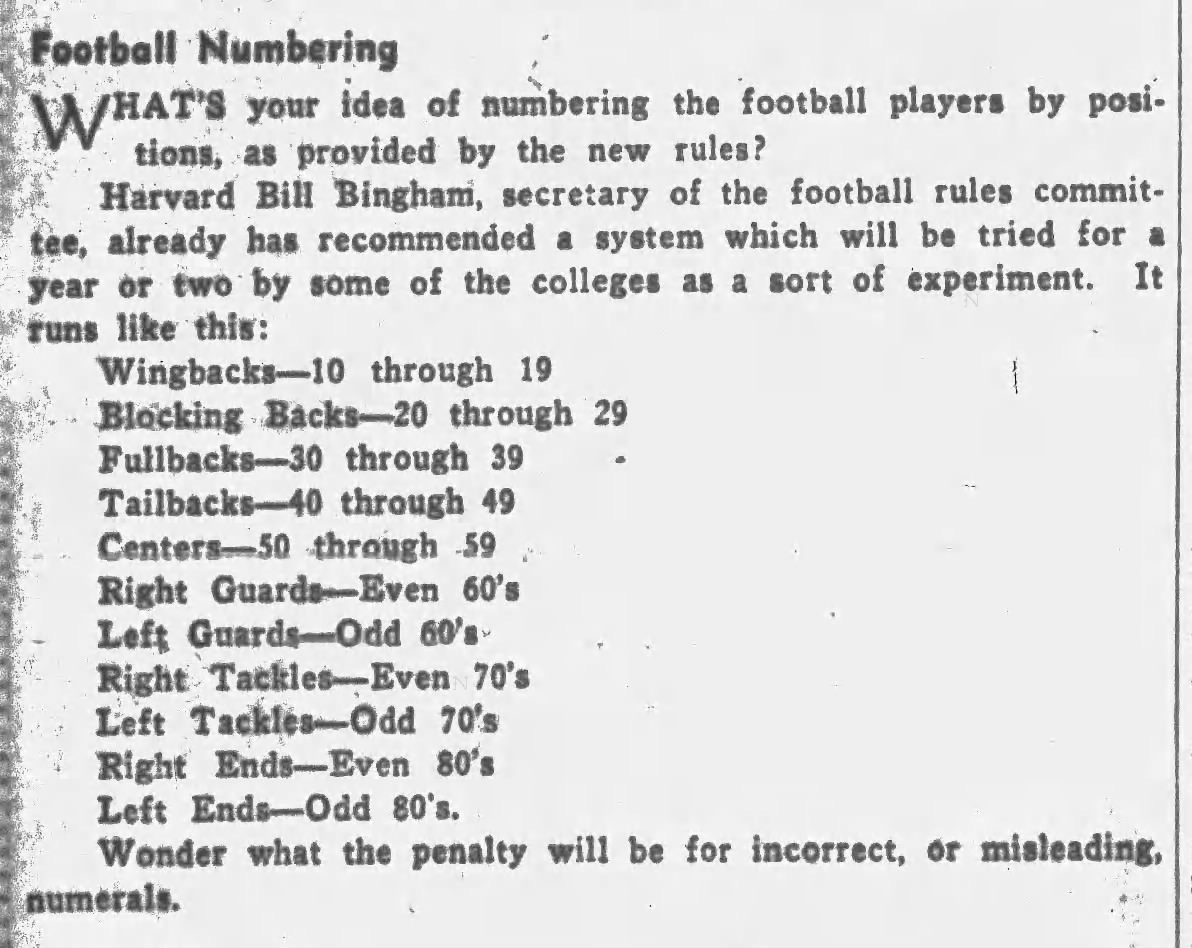

The stories concerning Karl Davis were written in 1941 when the NCAA recommended standardized numbering. However, the initial NCAA announcement did not recommend a specific number system, which opened the door to various numbering systems that made more or less sense. Each one makes sense, but it seems odd today because football selected a different path in the 1940s that now seems logical and preordained.

The first suggestion appears to have been the brainchild of Harvard AD, Bill Bingham. It is similar to the system that became universal but has two differences. First, the backs are defined based on the Single Wing or Notre Dame Box formations, with number sequences set aside for Wingbacks and Blocking Backs (aka Quarterbacks). Also, the linemen on the right side were to use even numbers, and those on the left odd numbers. (The odd-even thing saw some use and was part of the alpha-numeric systems also.)

In June 1941, the American Football Coaches Association recommended a similar standard. It used the same standard for the linemen but applied the Modern T formation's terminology for the backs:

10-19 Right Halfbacks

20-29 Left Halfbacks

30-39 Fullbacks

40-49 QBs

Before the 1941 season began, Creighton announced they would follow a system devised by Ray E. Fee of Omaha. His system required two-digit numbers with players aligned on the left using an odd number for the first digit and players on the right starting with an odd digit. The second digit corresponded to the player's position: Center = 0

Guard = 1

Tackle = 2

End = 3

QB = 4

Halfback = 5

Fullback = 6

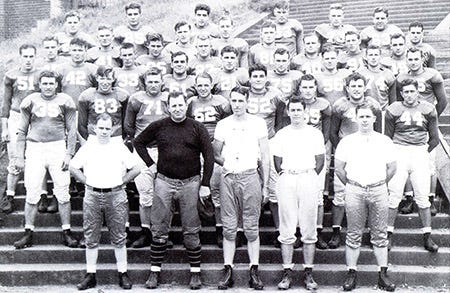

I couldn't find a picture of Creighton's 1941 team, and it is unclear whether the system was in place for the 1942 team, as shown below.

After the 1942 season, Creighton dropped football for the duration of the war. Apparently, Creighton is unaware that Japan surrendered since they have yet to return to the gridiron, so who knows what their numbering system will be when they make their comeback?

Another numbering system arose at Lodi High School in California. Devised by Flames coach Bill Archer, they hit the field wearing numbers in which the second or single digit corresponded to their position. Other area schools planned to adopt the system whenever they bought new uniforms. The Lodi numbering system worked as follows:

End = 1

Tackle = 2

Guard = 3

Center = 4

Backs = 5 through 9

The system was to be adopted by area schools as they bought new uniforms. Lodi's player numbers are difficult to read in the 1942 yearbook, but the 1943 yearbook images suggest they adopted the planned position since several players showing their blocking form in their poses have lineman numbers ending in 2 and 3.

Other numbering systems may await discovery, but while they proved helpful in identifying ineligible receivers, they are less meaningful in the positionless player era. The logic of some early number systems made more sense during football's single platoon era when a player's offensive role defined their position. Teams also tended to align in consistent formations more often, though they used more unbalanced lines. Numbering players by position has largely disappeared in favor of numbering by position group. By rule, players wearing numbers between 50 and 79 are ineligible receivers, but it's a free-for-all elsewhere. Defensive linemen often have numbers in the 90s, linebackers are in the 40s to 60s, and quarterbacks wear numbers in the single digits or teens. There is little rhyme or reason otherwise.

So, while the days of consistently numbering players are numbered, adding digits to jerseys has helped fans enjoy games by helping them identify their favorite players. Numbers also help officials penalize offensive linemen for being downfield on RPOs, so our favorite players are no longer as obscure as they would be otherwise. Thank goodness for progress.

Football Archaeology is a reader-supported site. Click here for options on how to support this site beyond a free subscription.