Postseason Football and the 1896 Yale Consolidated Team

From the beginning, postseason football involved a combination of the joy of sports, the opportunity to travel, good sports, and the chance to make a few bucks. Some things never change.

The Yale Consolidated team of 1896 was among the first to gain nationwide publicity for their postseason play. It was the brainchild of George Foster Sanford, who played for Yale in the early 1890s, graduated from Yale Law in 1896, and coached Cornell that year. He later had stints at Columbia and Virginia before an 11-year tenure at Rutgers, during which he volunteered.

Sanford's original vision involved a Southern barnstorming trip with current and recently graduated Yale players who were amateurs. However, Sanford planned to play himself, and the rules of amateur play were stricter then. Since Cornell paid him to coach, he was considered a professional, and any player involved in a game in which Sanford appeared lost their amateur status.

Sanford's team included players from Yale, Wesleyan Brown, and other schools. However, some doubted their true identities, and many Yalies preferred that the team not associate itself with Yale, regardless of the players' identities. Still, the name's value for promotional purposes meant the Yale Consolidated team remained in use.

News of the trip and potential games emerged the Friday after Thanksgiving. A game against the Nashville Athletic Club on Christmas Day was scheduled. The Southern Athletic Club, or Tulane's varsity, was reportedly a New Year's Day game in New Orleans, and other games were possible.

After Yale Consolidated announced a slate of five games, the team faced opposition from several fronts. Caspar Whitney, the writer who named the first All-American team, wrote a column criticizing the team for its commercialization of the game. Meanwhile, the Southern Intercollegiate Athletic Association, the SEC, ACC, and Southern Conference's forerunner forbade member schools from playing Yale Consolidated. (The same meeting saw the ban athletes from playing under assumed names and swearing on the field of play.) The Harvard Crimson suggested the Yale Consolidated tour likely would not take place due to the Yale, Brown, and Cornell elevens banning team members from participating.

The negative publicity seemed to matter in the Northeast but not in the South, where people just wanted to see their local teams compete against top Eastern competition. Other than Virginia being trounced by Princeton several times and North Carolina playing Lehigh, Southern teams had little to compare themselves against top Northern teams.

Despite speculation on the team's composition, Sanford wrote that he had the option for 25 men "who could be picked to go on a pleasure trip during the holidays." Eventually, 16 players, most of whom played for top Eastern schools in the previous or recent seasons, joined the tour.

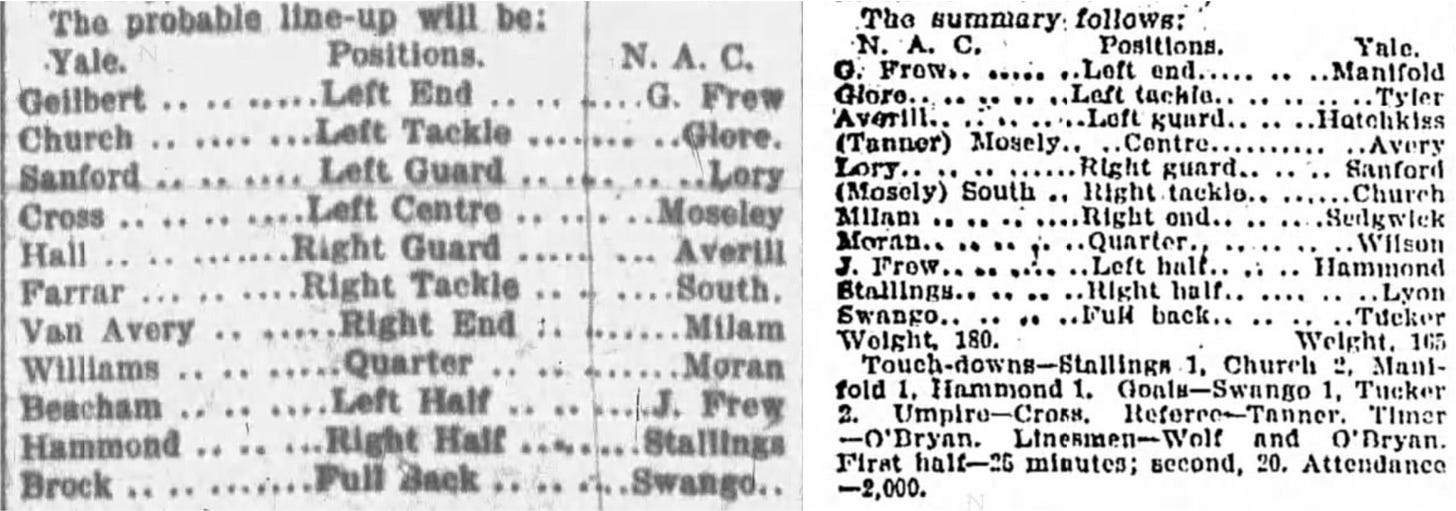

The players who were supposed to be on tour differed from the actual players, so the visitors' probable starting lineup published in the newspapers on Christmas Eve differed from the team that appeared on Christmas Day. However, the local promoters and newspapers continued referring to the visitors as representing Yale, dropping the Consolidated phrasing as needed, and attendance estimates varied by a factor of 10 during the trip.

Before a crowd estimated at between 2,000 and 20,000, Nashville AC, which was undefeated, saw the visitors jump to a 14- 0 first-half lead before narrowing the score to 14-6 and falling 20-6. Standing toe to toe with an august group of Northeastern athletes spoke well of the local boys and their manliness, and the fact the locals scored on Yale made the loss all the more pleasing.

The game served to show the people of Nashville that in the N. A. C. they have a team of which they should justly be proud. They were pitted against the pick of Eastern colleges -men who for years have stood at the very top of the ladder- yet the showing made against them was in every way worthy of commendation.

'Yale vs. N.A.C.,' Nashville Banner, December 26, 1896.

Their game against Southwest Baptist University (now Union University) in Jackson, Tennessee, received little coverage. Depending on the source, 1,000 or 10,000 fans witnessed the locals fall 38-4.

The final game of the tour was on the 29th when they beat the Alabama Consolidated team 30-0 in Birmingham before a reported 2,000 fans. That game also received little mention in print.

However, the Alabama game may not have been the final one for some players since Nashville AC had a game with Southern AC in New Orleans on New Year's Day. Yale Consolidated originally planned to play Southern AC that day, but the game did not materialize for one reason or another. Instead, Southern AC played the Nashville AC team, though the New Orleans team claimed a few Yale Consolidated players might have volunteered or received payment for playing with Nashville that day.

The team returned to the Northeast early in the New Year, but not before its sleeping car derailed north of Washington, D. C., on the trip home. The derailment may have been symbolic of the trip itself, as reports indicated it had not been the financial windfall the players had hoped it might be. The opponents were not what they had hoped, and neither were the crowds.

Of course, neither was the Yale Consolidated team. After the fact, a source that investigated the team members indicated the team essentially included players from top programs of the time. Still, Sanford and Hammond were likely the only players who had played for Yale's varsity. The lineup appears to have included:

Center: Avery, a Yale grad student who had not played football at Yale

Guard: Sanford and Hotchkiss, the captain of the 1895 Crescent AC team of NYC (a top team of the era)

Tackles: Tyler and Church of Princeton

Quarterback: Wilson of Wesleyan

Halfbacks: Hammond of Yale Medical School and Lyon of Central College

Fullback: Tucker of Princeton

Ends: Sedgwick of Brown and Manifold of Yale Medical School

Despite the trip's lack of financial success, it helped open the door for postseason barnstorming teams and teams from other parts of the country to travel to warm-weather locations for a game of football or two. Had it not been for Yale Consolidated, we may not have developed the bowl tradition we have enjoyed for the last century and more.

Football Archaeology is a reader-supported site. Click here for options on how to support this site beyond a free subscription.

I missed this article when first published so I shouldn't have been as surprised about the Yale team when I sent my recent communication about Princeton's Gordon Johnston playing for the Alabama team.

Wow, What a road trip that must have been for the boys!!