How We Forgot, Then Remembered The 1902 Rose Bowl

All history is revisionist history. We understand our past by continually redefining as new facts emerge, and we reinterpret old ones. As a result, facts that seem indisputable become disputed when given enough time.

Take, for instance, an example from the football world. Today, if you ask the average football fan or a historian of the game when they played the first Rose Bowl game, they will tell you it occurred in 1902. However, if you transported yourself back to the early 1930s to ask the same question, they would say the first game came in 1916. What gives? How could people living ninety years closer to the actual event provide the wrong answer to a question whose answer is widely known today?

Of course, the difference is one of perspective due to the fourteen-year gap between the first Rose Bowl and the second, but also because people closer to the events in time saw the two events as disconnected rather than connected.

Although the Tournament of Roses started in 1890, it was not until 1902 that a football game became part of the festivities that celebrated and promoted Pasadena and its real estate values. Michigan trounced Stanford 49-0 in 1902, and while a suburban legend says the Tournament folks did not try to schedule another game until 1916, they invited Wisconsin to play in 1903 but could not convince Cal or Stanford to play in the game.

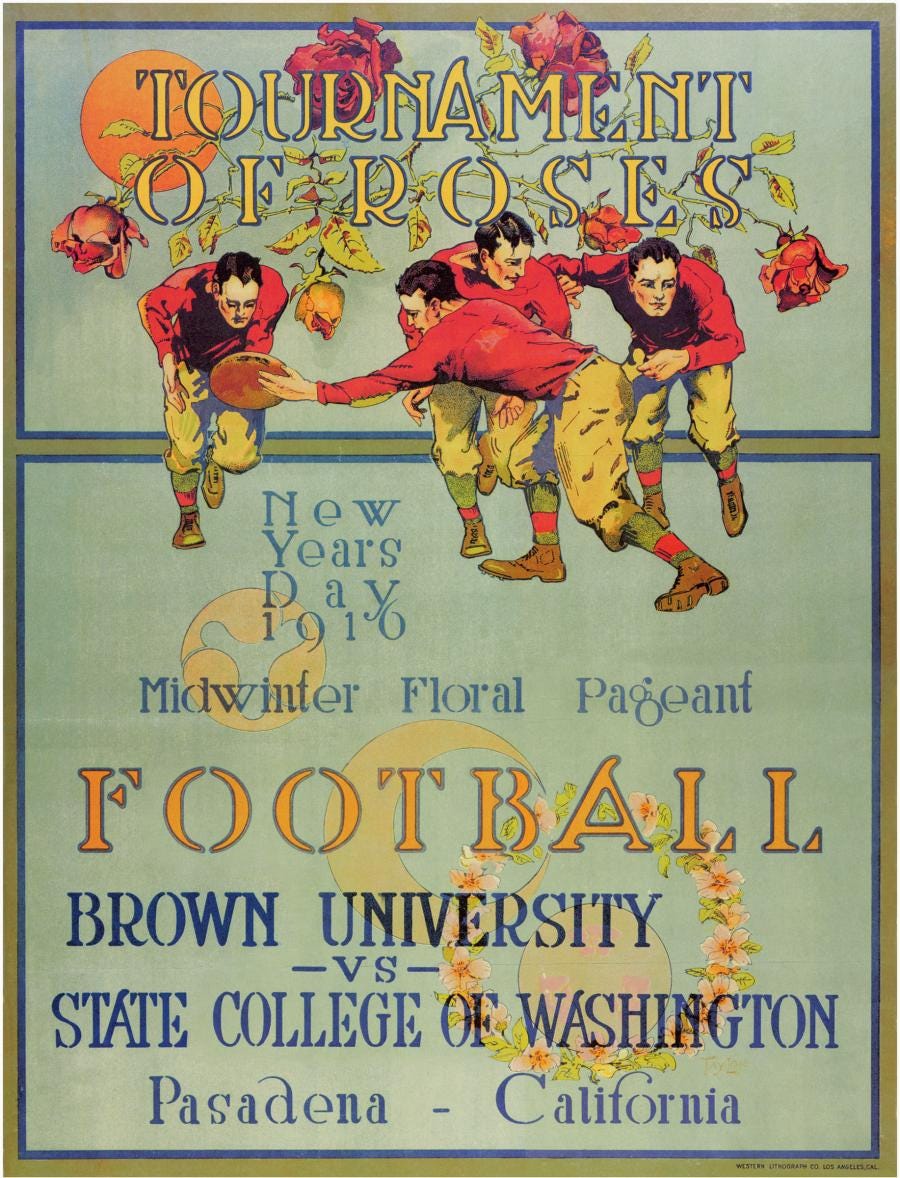

Cal, Stanford, and others on the West Coast dropped football in 1906 and played rugby instead. Cal brought football back in 1915, which may have provided the stamp of approval for the awkwardly-named Tournament East-West Football Game. Brown and Washington State accepted invitations to play in the game won by the Cougars. Oregon and Penn played in 1917, and the games grew in popularity, so they outgrew the wooden bleachers at Tournament Park by the early 1920s. The Tournament folks built the massive concrete Tournament of Roses Stadium in time for the 1923 game. In the lead-up to the game, a local writer referred to the stadium as the Rose Bowl. The name stuck and soon came to refer not only to the stadium but to the game and, more broadly, to "bowl games" and "bowl season."

During the 1910s, 1920s, and much of the 1930s, people did not connect the 1902 game to the annual games that started in 1916. Newspaper reporters and others consistently viewed the series as beginning in 1916.

Since 1916, when the first East-West game was played, the western representatives have won three, the eastern teams have won one, and one game has been tied. (Note: This count includes college games only and excludes the 1918 and 1919 games between military teams.)

'West Leading In New Year's Grid Contests,' Pittsburgh Daily Post, January 1, 1923.

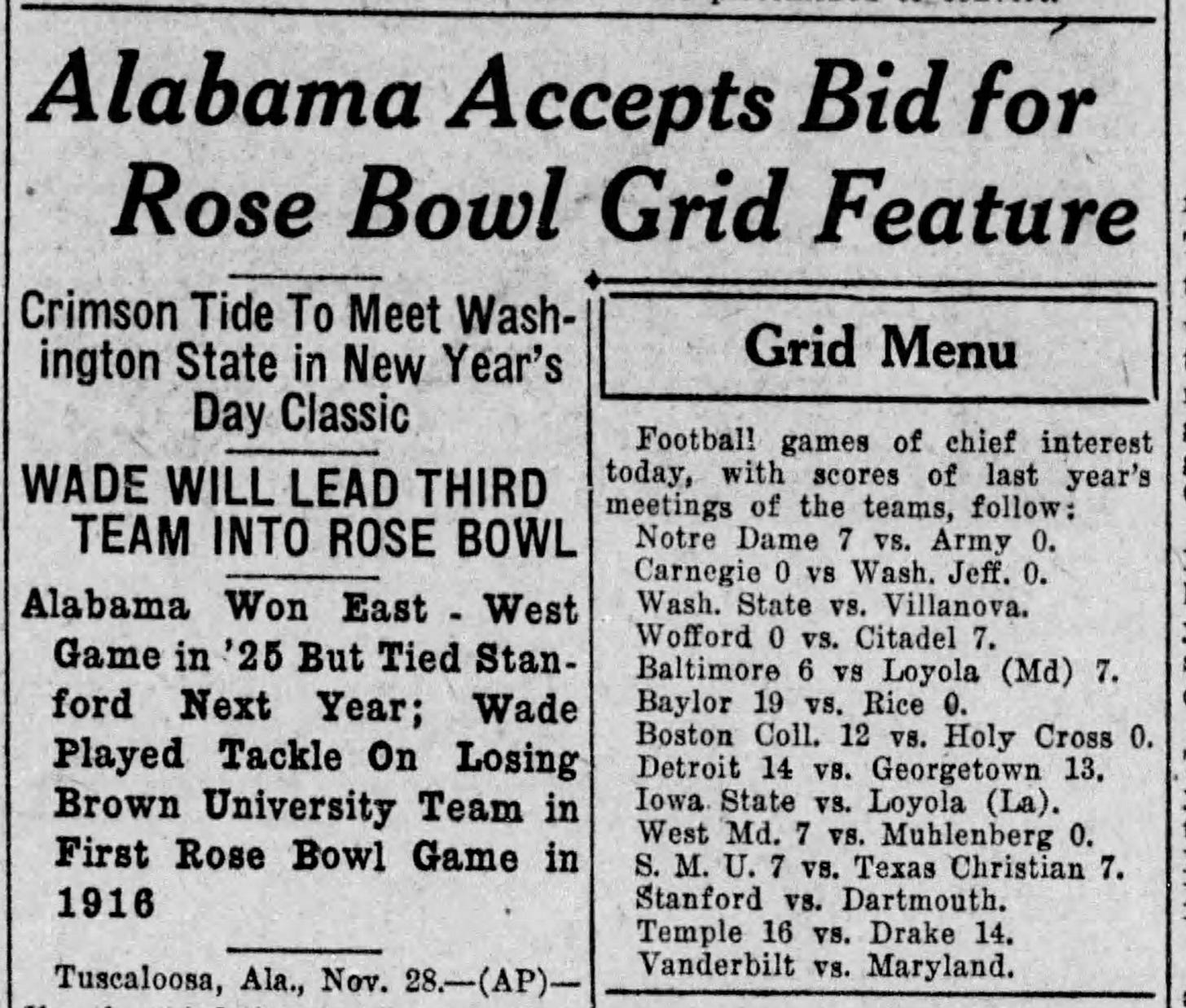

The history of the Rose Bowl drew attention before Alabama's appearances in 1926, 1927, and 1931 because Alabama's head coach, Wallace Wade, played for Brown in the 1916 contest. Wade later coached Duke in the 1939 and 1942 games, and each game brought reminders that Wade was on the field for the first Rose Bowl, as seen in the following subheader.

Even the Angelenos did not remember the 1902 game, as demonstrated by a Los Angeles Times article describing the 1931 halftime show featuring a book telling the Rose Bowl story:

The first page told of Washington State's 14-0 victory over Brown in the first Rose Bowl game back in 1916.

'Coaching Edge Won For Tide,' Los Angeles Times, January 2, 1931.

Evidence of the Southern Californians' collective poor memory comes from the Rose Bowl game scores in a football schedule produced as a giveaway for LA's Eaton's Steak House in 1936. Note that the schedule's producer was bogardus & bogardus, a Pasadena-based advertising firm.

The situation repeated itself in a national schedule giveaway prepared for Shell Oil the following year.

Still, the 1902 Rose Bowl received periodic mention in the 1930s, and the phrase “1902 Rose Bowl” appeared in a newspaper for the first time in 1932. The 1902 game was not commonly tacked on to the list of Rose Bowls until the 1940s, thanks to Fielding Yost regularly reminding newspaper columnists and others of the game he coached in 1902. His perspective gained a boost when the top sports columnist of the era published a story unearthing the 1902 connection and crediting the discovery to an Ann Arbor-based correspondent, which likely was Fielding Yost himself.

Connecting the 1902 game to its counterparts took time, but people slowly adopted that view until everyone accepted that version of the truth. And the rest, as they say, is revisionist history.

Football Archaeology is reader-supported. Click here to buy one of my books or otherwise support the site.