Sammy White's Moments Of Glory

The 1911 Harvard-Princeton game was a doozy that followed a fourteen-year span during which the schools did not play one another. Few conferences existed around the turn of the century, and they focused on eligibility requirements rather than scheduling, so when one school upset another, they stopped playing one another. But Harvard and Crimson decided to let bygones be bygones in 1911 and scheduled an early November game at Princeton's Osborne Field.

The game was notable not only for the play on the field but also for events that occurred above the stadium. During a tight battle, the crowd's attention was diverted by a hot air balloon that hung over the stadium for a bit. More noteworthy was a Wright biplane piloted by Robert Joseph Collier, an aviation enthusiast and publisher of Collier's Weekly. Flying both Harvard and Crimson pennants, the plane's only passenger was James Hare, a top photographer of the day, who, among other things, took the first photograph of a football game from an airplane.

Princeton entered the game with limited expectations, standing 5-0-2 with ties against Lehigh and Navy, while Harvard was an untested 5-0. Still, the game hinged on the play of a multi-sport Princeton athlete, Sanford B. "Sammy" White didn't play football as a sophomore and did not start for the football team as a junior. Named the baseball team captain for the 1910 season, he started a left end as a senior but had not done anything noteworthy until the Harvard game.

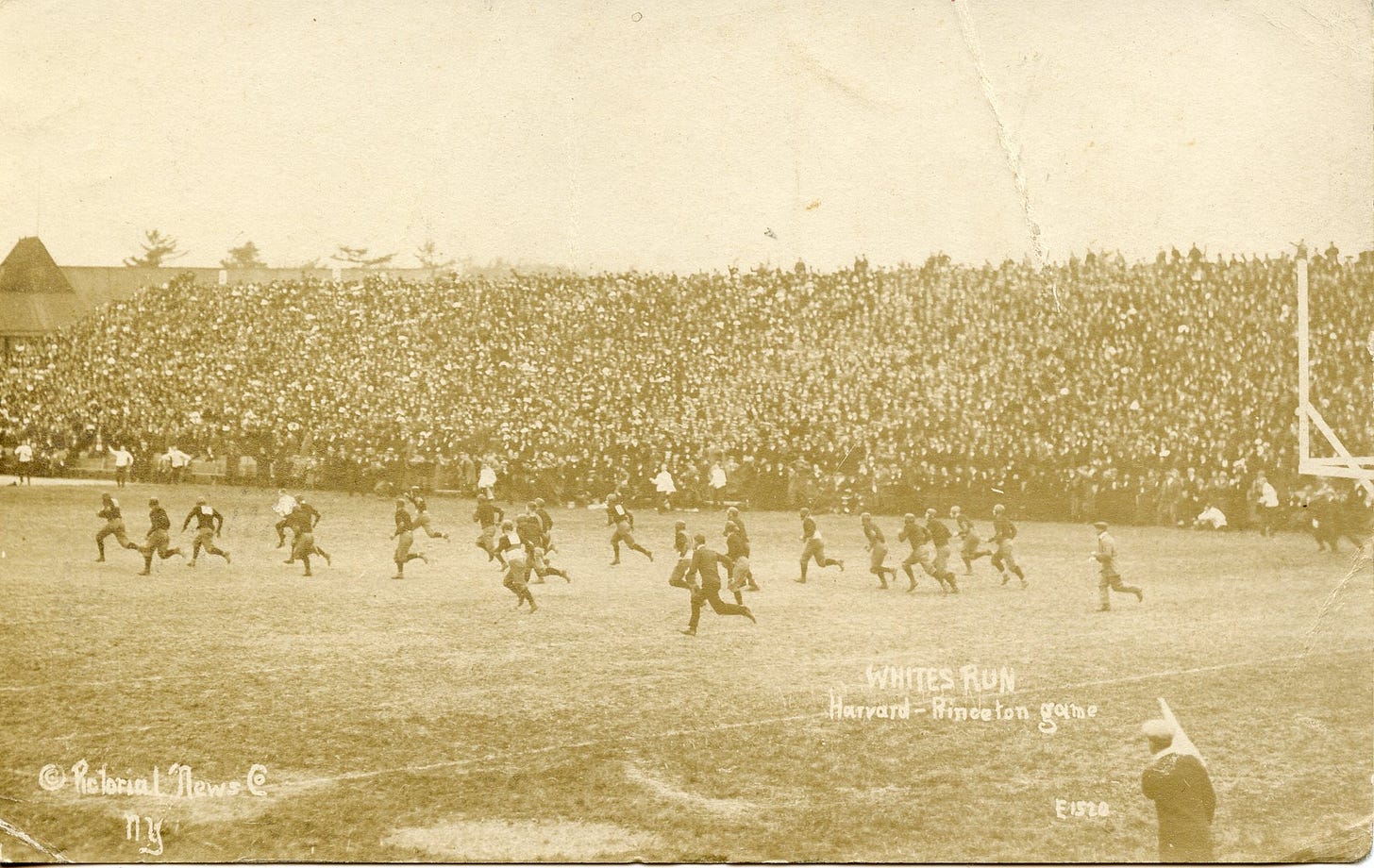

Harvard moved the ball to Princeton's 10-yard line during the second quarter before being stopped when they elected to attempt a drop-kicked field goal on third down. The Harvard kicker received a clean snap, but Princeton's right guard, Duff, shot through the line and blocked the kick, sending it bouncing on the turf, where Sammy White picked it up. White ran as he never had before toward Harvard's goal line, picked up a block, and was in the clear, ultimately planting the ball across the line and between the goal posts, giving Princeton a straight-on conversion attempt, which they made to take a 6-0 lead.

During the third quarter, White was the gunner covering a booming Princeton punt which sailed over the Harvard return man's head, positioning the returner near his goal line. He attempted but failed to evade Sammy White, who tackled him behind the goal line zone for a safety, making it 8-0 and a two-score game.

Harvard earned a touchdown and conversion later, but the game ended at 8-6, with Sammy White making seven of Princeton's eight points.

The next week, Princeton defeated an unexpectedly tough Dartmouth squad 3-0, setting up their season finale with 7-1 Yale, whose only loss came at Army, 6-0. In that game, Army picked up a Yale fumble in the rain-soaked game and took the ball to Yale's 3-yard line, scoring two plays later.

Princeton closed its season in a game played in the rain and mud at Yale Field against a Bulldog team they had not beaten since 1903. During the first quarter, Yale crossed into Princeton territory only to have a Bulldog lateral go wild. Once again, White was Sammy on the spot, reaching into a puddle to grab the ball at the 45-yard line and begin racing downfield. With the Yale team in hot pursuit, a Yale player leaped for White, tackling him at the 5-yard line, but the mud did not stop either player as they slid past the goal line. Football's rules of the time required stopping the ball carrier's forward progress. Taking him to the ground was insufficient, so White received credit for a touchdown on the play. His teammate, Hobey Baker, converted for Princeton to give them a 6-0 lead.

Yale kicked a field goal in the second quarter to make it 6-3, but both teams had difficulty moving the ball the rest of the game, with both punting frequently. The difference was that Yale fumbled multiple Princeton punts. At the same time, Princeton's Hobey Baker fielded them cleanly, setting a Princeton record by fielding 13 punts during the game and keeping Princeton in a favorable field position.

Neither team scored after Yale's field goal. Princeton earned a victory to cap what football historians would later designate as a national championship season. White, who was otherwise not a football star, was named an All-American, based mainly on the two biggest plays in two big games. His legend continued growing in some circles, leading him to be compared to Red Grange in a 1925 illustration. Still, despite the reputation inflation, ol' Sammy did what he did back in 1911 and is today remembered among Princeton's football immortals for those deeds.

Football Archaeology is reader-supported. Click here to buy one of my books or otherwise support the site.

One sidenote (literally) that helped change the course of American writing: In the stands for that game against Harvard was a prep school student who was pondering which college to attend. After the Tigers' victory, F. Scott Fitzgerald wrote: "Sam White decides me for Princeton."

Hobey Baker is the only athlete to be inducted into both the hockey and college football halls of fame.