Sideline Plays and How We See the Past and Future

Studying history helps us understand that each of us understands the world through a unique perspective that results from the time and place we were born, educated, and all our life experiences. For example, as someone living in 2023, it isn't easy to see the world through the eyes of someone living in the 1920s and 1930s because we bring a worldview informed by the events of the last 100 or 90 years. Likewise, try as they might, those living in the 1920s and 1930s struggled to see the future, resulting in blind spots about elements of the world we take for granted.

Those fancy thoughts occurred to me when digging into this story, which addresses sideline plays. Sideline plays have been covered previously in the history of hash marks, and a Tidbit about sideline plays specifically. Read those stories if interested, but I'll provide a short version of the relevant information for the poor souls who are too lazy to read those stories.

As you may know, football fields did not have hash marks until 1933. When the ball went out of bounds, the last team to touch the ball could bring the ball infield fifteen yards and start the next play there. However, when a ball carrier was downed inside the sideline, the next play started from that spot, regardless of whether that was one foot, one yard, or twenty yards from the sideline. Like golf, you play the ball as it lies.

Of course, teams running plays when pinned against the sideline had reduced play-calling options, so much so that teams often deliberately ran the ball out of bounds on the next down. That meant the next play started fifteen yards infield, where they could use more of their playbook on following down. (The strategy behind wasting the down was analogous to teams spiking the ball to stop the clock today. Every practiced sideline plays, but most coaches kept it simple and ran the ball out of bounds rather than spending significant practicing times on plays unlikely to gain ground.)

One aspect of these plays illustrates the difficulty of seeing the world through the eyes of those living in different times. Specifically, under today's rules, defensive players are not instructed to tackle the ball carrier inbounds except when it is late in the half and the offensive team wants to stop the clock. Under that circumstance, tackling the ball carrier inbounds is considered intelligent defensive play.

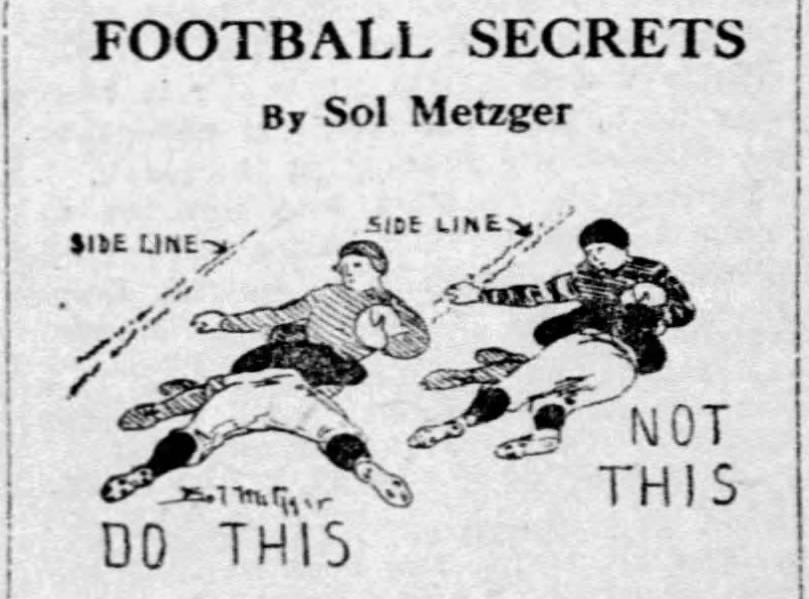

I've been familiar with the old sideline plays for some time. Yet, I only recently realized that pre-1933, coaches taught players to tackle the ball carrier inbounds on every play because tackling him near the sideline reduced the offense's options on the next play. As Sol Metzger told readers in 1926:

...when a player tackles an opponent near a side-line, he should use all his strength and ingenuity to prevent that runner from going out-of-bounds. Every runner tackled in this position will do all in his power to get out-of-bounds.

Metzger, Sol, 'Football Secrets,' Boston Globe, October 16, 1925.

So, while focusing on keeping the ball carrier inbounds throughout the game is not an earth-shattering idea, I suspect that few living today recognize the implication of football's pre-1933 rules.

Sideline plays also illustrate how we cannot predict the future, even near-term ones. The frequency of teams running the ball out of bounds when along the sideline was a frequent complaint among fans and in the press in the 1920s. In 1930, a panel of football coaches recommended to the NCAA rules committee a rule change to automatically move the ball fifteen yards from the sideline whenever it became dead within fifteen yards of the sideline. Of course, this is the core idea behind hash marks, which the NCAA and the NFL adopted in 1933. (It is worth pointing out that while the 1932 NFL Championship game played indoors on a reduced-size field often gets credit for football's adoption of hash marks, college coaches recommended the rule two years before that game.)

So, in late 1932 as the idea of automatically moving the ball infield entered the national discussion, some were concerned the rule would slow down the game, forcing the officials to measure whether the ball was within fifteen yards of the sideline and then walking off the fifteen yards to place the ball. It is obvious that a line or set of lines fifteen yards in from the sideline eliminated the need for the officials to measure those distances. Still, if your football world never had hash marks, you might now think to add that marking to the field. And, while the coaches in 1930 recommended adding a continuous line fifteen yards in from either sideline, not everyone got that memo, so those criticizing the rule did not foresee the simple solution that would solve the problem a few months later.

Besides their inability to foresee hash marks, no one understood the dramatic impact hash marks would have on the game. As I argue in How Football Became Football and the history of hash marks article, hash marks were among the eleven most important innovations for shaping the game today. No one foresaw that in 1932 since they, like we, could not foresee how specific rule changes might reverberate in ways we cannot anticipate.

Football Archaeology is reader-supported. Click here to buy one of my books or otherwise support the site.